What is Toumeikan?

You are so transparent.

You are water-drippingly handsome.

These are compliments in Japanese—odd ones, maybe. Toumeikan(透明感), directly translated as “sense of transparency,” is a common phrase used to praise someone’s… well, transparent beauty. Transparent, like water: clear, cool, fresh, light, reflective and pure. But what exactly does it mean to look transparent?

There is a common Japanese phrase, mizu-moshitataru ii otoko—literally, “a man so handsome, water drips from him” (more commonly, though not exclusively, used for men). Originally describing “hot” kabuki actors in the Edo period, it evokes the image of youthful and dewy-skinned beauty.

Today, it’s used more broadly to describe fresh-faced heartthrobs, but the water imagery lingers.

Water and toumeikan are aesthetic ideals in Japan, not only for the way you look but also for art and

its philosophy. This topic, after all, is as deep as the Mariana Trench. To wade into why water and

toumeikan carry such weight in Japanese aesthetic ideals, we have to talk about Pocari Sweat ads,

vaporwave, Shinto rituals and ukiyo-e.

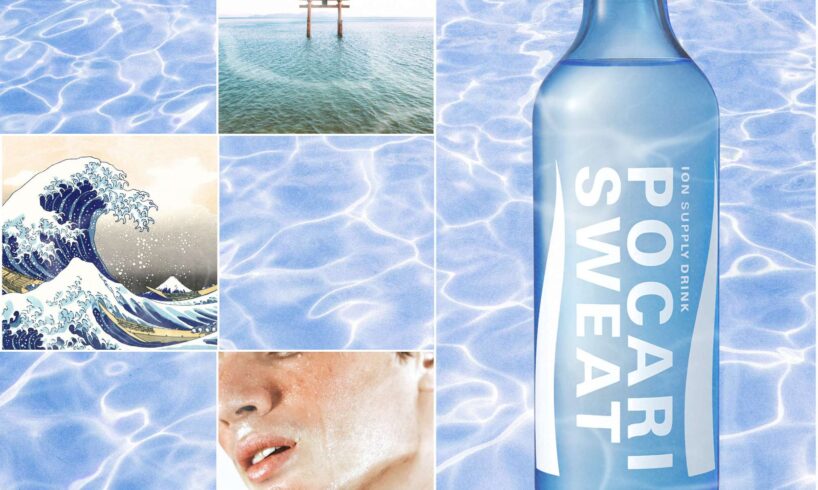

Toumeikan in a Bottle? The Pocari Sweat Aesthetic

Pocari Sweat Commercial (2015) / Courtesy of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. via PR Times

Cosmetic brands might tell you that toumeikan is about sheer makeup and luminous skin.

Skin so dewy it could be described as mizu-moshitataru, like freshly picked fruits still beaded with

moisture. Or they might claim it can be achieved by incorporating cool-toned colors like blue. But

toumeikan isn’t just about appearance. It’s a funiki, a vibe, an aura, an atmosphere. A sense of freshness

and purity, like water itself. When I try to explain the aesthetic ideal of toumeikan, I often point to an unlikely cultural symbol: Pocari Sweat. Yes, the electrolyte drink.

Pocari Sweat commercials are widely recognized in Japan as embodying toumeikan, and have developed

something of a cult following. Often filmed with soft, blue Fuji-film hues, they feature wind, light

and lots of water, usually against a backdrop of high school students running on rooftops, drinking

Pocari after practice or staring into the blue sky. It’s a visual shorthand for seishun—a word that

literally means “blue spring,” but culturally refers to the period and feeling of youth.

For many English speakers, the word “sweat” on a drink label can feel off-putting. However, in this

seishun imagery, they run, they sweat, but it’s not sticky or gross. It is a kind of refreshing sweat that

runs down your cheeks like morning dew. As the phrase mizu-mo-shitataru suggests, it’s a poetic

compliment. The actors in these commercials are almost always fresh-faced newcomers—so much so

that landing a Pocari ad is seen as a kind of a rite of passage for rising stars, known in Japanese as

touryumon, a term drawn from the Chinese legend of koi that swim upstream and leap over a waterfall

to become dragons.

credit: istock / @Swillklitch

© RightCowLeftCoast / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-4.0

It might seem strange for an electrolyte drink to carry this much aesthetic weight. A Western

equivalent might be Fiji Water in vaporware, a retro-futurist internet aesthetic rooted in 80s

and 90s remix culture, with heavy influence from Japanese media like city pop and anime. Fiji Water

became an unexpected “water” icon, appearing alongside Roman busts, Windows 95 logos and

Japanese text.

Vaporwave also uses water imagery for its surreal and relaxing feel: tropical pools, mall fountains,

light reflecting on smooth surfaces. Interestingly, since the genre often repurposes Japanese ads

and packaging, Pocari Sweat has also appeared in vaporware.

Originally launched in the 1980s, Pocari Sweat struggled at first. However, the brand invested heavily in advertising, not just to promote the product name or ingredients; but to sell a sekaikan: a visual world and mood, much like a perfume ad. This aesthetic vision made waves, entering the high-speed landscape of Japan’s bubble economy to become a Japanese summer staple.

A distilled memory of 80s and 90s youth, summer humidity and glistening blue skies. The Pocari

girl, mid-run, cheeks shimmering with sweat, settled into the collective aesthetic subconscious,

just as Coca-Cola became a symbol of vintage Americana. Beyond its hydrating, watery freshness,

Pocari Sweat became an icon of Japanese youth and the “good old days,” serving as a reference point for toumeikan in both the domestic imagery of seishun and the Western internet’s borrowed nostalgia.

And in Japan, a drink bottle becoming a style accessory isn’t as strange as it sounds. At one point, girls began repurposing Evian bottle labels as smartphone case inserts—not for hydration, but for their clear, watery funiki.

Shinto Purity and the Japanese Aesthetic of Water

Touimeikan, water and Japanese aesthetics go deep into history, far beyond the bubble era of the 1980s and 90s. It goes way back.

In Shinto, the indigenous faith of Japan, water plays a central role. After all, Shinto is a religion

of purity. It teaches that humans are born “pure,” and that kegare (impurity) is something picked up

through daily life, just like dust and dirt you collect on your body and clothes as you go about your day outside.

Fortunately, impurity isn’t permanent. Wash it off, and you return to your pure state. At the entrance of every shrine, visitors perform a ritual hand-washing at the chozuya, a stone basin filled with flowing water. It’s a quiet, reflective act meant to cleanse the hands and mouth, washing away spiritual impurities before approaching the divine.

In addition to purity, Shinto, like many animistic beliefs, emphasizes nature and living in harmony

with powerful natural forces. Flowing water, rivers and waterfalls are especially sacred, believed to

cleanse both body and spirit. Because purification and nature go hand in hand, some practitioners continue to perform takigyo today, standing beneath a waterfall to wash away spiritual impurities. Clear

water is pure in itself, and capable of purifying other things.

Of course, Gen Zs slipping Evian bottle labels into their phone cases probably aren’t thinking about waterfall purification rituals. But Shinto values do seep into everyday life and what we consider “ordinary” Japanese culture. The obsessive handwashing and gargling many Japanese kids are taught from an early age— the idea that you do this combo the moment you come home, before you touch anything or… breathe? The preference for nighttime bathing, to wash off the outside world’s kegare before entering the sacred space of the home? All of it stems from, or is at least influenced by, Shinto. So it’s no surprise that visual ideals would flow with the same tide. In a culture where water purifies, transparency becomes beauty. Water is a visualization of purity, and toumeikan is an articulation of its aesthetic appeal.

Visualizing Water in Art Through Blue

The Great Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura) by Katsushika Hokusai

Water represents purity, but it also reflects Japan’s favorite philosophy: impermanence. It’s fluid, never still. And it constantly transforms: into ice, snow and vapor, surrounding our lives in countless forms, just as it does around the world.

Water can also be powerful. The tsunami, a terrifying force of nature, has been etched into Japanese memory for centuries, passed down through generations as both fear and a lesson. And yet, the same combination of water and geological activity gave rise to one of Japan’s greatest gifts: the onsen.

Unsurprisingly, water appears again and again in Japanese art. The most internationally recognized

ukiyo-e print, Hokusai’s “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” from Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, has become an icon of Japanese visual culture.

This iconic work might never have existed without the then newly invented color: bero-ai (lit. Berlin Indigo), also known in English as Prussian blue. This synthetic dye, imported from Prussia via the Dutch in the 1780s, changed ukiyo-e forever.

Before this, ukiyo-e artists used a cultivar of Asiatic dayflower for blue, but it faded quickly and turned yellow over time. The more stable Japanese indigo dried down muted, dark, and warm-toned—lacking clarity—and its gritty texture made it unsuitable for smooth gradients.

Bero-ai, on the other hand, was cool-toned, vibrant and worked like a miracle. It was water-soluble,

making it ideal for bokashi-zuri (a gradient shading technique). Even when dry, it retained luminosity and clarity. For the first time, artists could render water with brightness and depth—the toumeikan they so

often pursued.

The ripple effect of this blue craze created a new trend: aizuri-e, prints created entirely in shades of Prussian blue. By layering and using noutan (gradations of light and dark), artists could express depth and transparency with a single color.

The same bold blue was an unusual choice for Pocari Sweat at the time, as blue wasn’t considered appetizing for food or drink. Much like Hokusai choosing Prussian blue to evoke the depth of the ocean, Pocari Sweat embraced the association with water and refreshment.

While transparency isn’t a color, you can visualize the lack thereof.

Maybe this has all been a roundabout way of saying, “water and toumeikan are aesthetic ideals in Japan,” but still waters do run deep.

From the ukiyo-e waves to the dew-like sweat in a Pocari ad, toumeikan isn’t something you can bottle.

But we keep finding new ways to show what it feels like.

Drawn to water? You might also like:

Artist Tomei: Curating Transparent Life (+Aesthetic Jelly Recipe)

Sento Architect Kentaro Imai and the Art of Bathing Spaces

Is Tap Water in Japan Safe to Drink?

More on Japan’s visual culture, aesthetics and design in our other articles:

Dami Lee on the Organized Chaos That is Tokyo

Japandi: The Fusion of Japanese Minimalism and Scandinavian Comfort