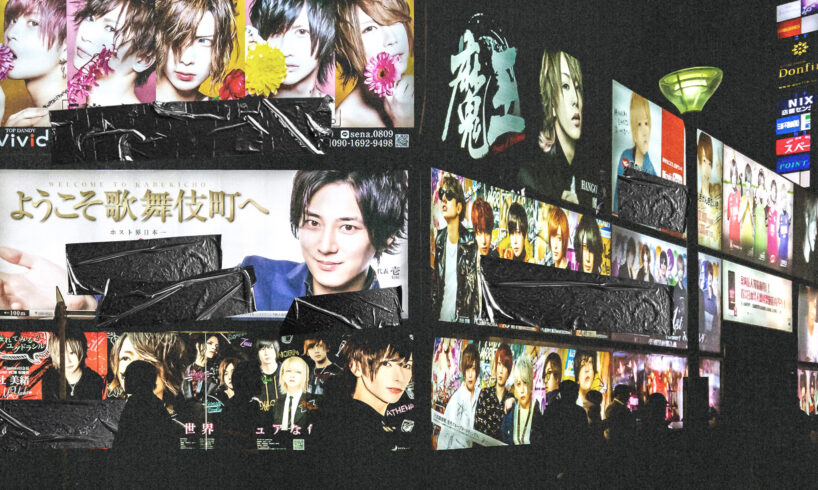

Towering faces of impossibly perfect men stare down from glowing billboards in Kabukicho, the infamous nightlife district in Shinjuku. These are hosts, charismatic young men who work at upscale clubs, pouring drinks and charming clients with practiced flirtation. The billboards all offer the same seductive image: porcelain skin, razor-sharp suits and gazes that promise love — or at least the illusion of it. Beneath their faces, bold proclamations boast of their success: “Annual sales over 100 million yen” or “No.1 requested host.”

But now, something’s changed. Those same signs are marred with strips of tape, covering up the words that once boasted of money and status. On June 27, workers could be seen quietly pasting over the slogans. Look closely at what’s been hidden, and you can still trace the faint outlines of what was there: Sales King. Champion. Legend.

What could make Kabukicho suddenly censor its own fantasies?

The New Law

On June 28, a revised law came into effect, targeting the darker side of Japan’s host club industry. The amendment makes so-called “romance sales tactics,” where hosts exploit a customer’s romantic feelings to pressure them into excessive spending, explicitly illegal.

The change was driven by a growing social problem: women racking up exorbitant unpaid tabs, known as tsuke, and then being coerced into working in sex-related businesses or appearing in adult videos to pay off their debts.

Under the new law, not only is this kind of coercion a criminal offense, but operators of sex industry businesses are also barred from paying hosts referral fees for introducing women to such work. Violators face up to six months in prison, fines of up to ¥1 million or both.

Discover Tokyo, Every Week

Get the city’s best stories, under-the-radar spots and exclusive invites delivered straight to your inbox.

Advertisements and promotions for host clubs are also now under scrutiny. In a June 4 directive on the handling of ads in hospitality businesses, the National Police Agency clarified that any promotion creating an overly “pleasure-seeking, indulgent atmosphere” that fuels customer spending or stokes competition among hosts — and in turn encourages illegal practices — would be considered a violation.

The directive laid out clear examples of banned language. Phrases flaunting sales figures, like “Annual sales over 100 million yen” or “No.1 requested host,” are now off-limits. Titles that suggest high status based on performance — “Champion,” “God,” “Legend” — are likewise prohibited. So are words that emphasize rivalry between hosts, like “Sales battle” or “Total SNS followers: 50,000.” Slogans that push customers to obsess over their favorite host, such as “Support XX” or “Drown in XX” have also been deemed excessive.

If a sign or ad violates these rules, local public safety commissions can issue corrective orders. Repeated or egregious offenses risk administrative penalties, including business suspension.

The End of the Sales King Era

Projecting an image of success has always been the lifeblood of host club marketing. The illusion of scarcity — that a host is in such high demand that time with him feels like a coveted privilege — has long been a powerful tool. Combine that with enough personal attention to make a customer feel special, and the result is a potent mix of ego, desire and social competition. It’s a formula that keeps customers coming back, often spending far beyond what they can afford to ensure their favorite host remains one of the club’s best and brightest.

But that game is over, at least in terms of what can be plastered on billboards. With bold rankings and sales figures now forbidden, host clubs are left scrambling — covering their signs with strips of tape, paint or paper in a hurried act of self-censorship. For now, it’s a temporary patch until new, compliant signs are printed. Still, it signals a clear shift: Host club advertising in Kabukicho will never look quite the same.

Even online, the change is obvious. Until recently, host club websites openly ranked their staff by monthly or quarterly earnings. Next to each profile photo were titles like “100-million-yen player” or “top earner this month.” Now, those rankings have disappeared. The numbers are gone, leaving only basic profiles without the status markers that once defined them.

The reactions from within the industry are largely negative. “It’s tough. I think it’ll be harder to keep our female customers motivated. Seeing the results — like, ‘I’m the one paying most of this massive sales total’ — meant something to them. Losing that is sad. Honestly, I can’t accept it,” said one current host to Prime Online FNN.

For outsiders like Chiwawa Sasaki, a writer who closely follows the host industry, the impact is profound. “Kabukicho is in chaos. Sales will likely drop significantly. They’ll have to change the way they get customers to spend money and the way they build support,” Sasaki told Prime Online FNN.

And maybe that’s not a bad thing. A business model that thrives on emotional manipulation and exploitation was always built on fragile ground. Stripping away the loudest, flashiest tools of persuasion won’t erase the fantasy entirely, but it may dull some of its more coercive edges.

Whether this legal overhaul will truly reshape the business, or simply force it to find subtler ways to sell the same dream, remains to be seen. But for now, Kabukicho’s glowing faces are a little less dazzling.