“Building and housing is the social issue of our time,” Germany’s new Construction and Housing Minister Verena Hubertz told public broadcaster ARD in May when she announced her plan to help ease the shortage of affordable housing.

With the cabinet set to present its 2026 budget proposal on July 30, spending on housing is one of the focal points.

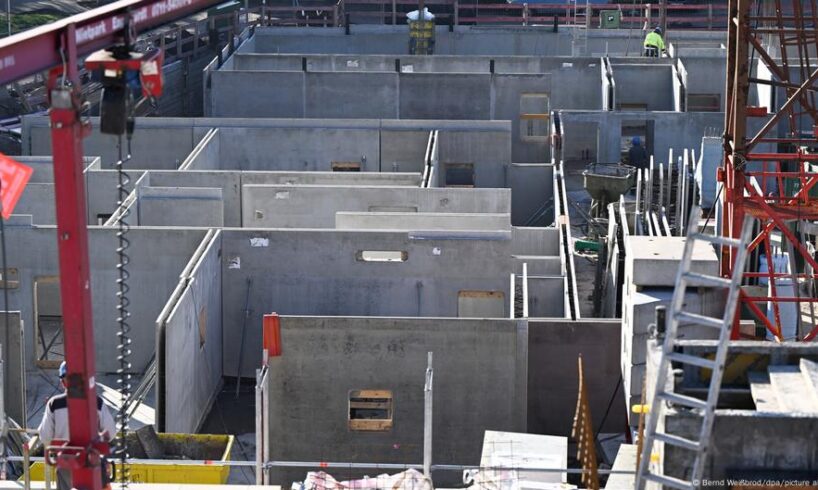

In a country where it can take longer to get approval for a development project than it does to actually build it, Hubertz said she wanted to give local authorities a “crowbar” to circumvent labyrinthine urban planning laws. That crowbar, labeled “Bau-Turbo” (construction turbo), is a new paragraph (§ 246e) to be inserted into the German Building Code.

If the legislation is passed in the fall, municipalities will be able to approve construction, change-of-use and renovation projects that deviate from the provisions of the Building Code if those projects are for the construction of new residential buildings.

Planning applications will also be automatically approved after two months unless vetoed by the municipality.

Germany: Augsburg’s practically rent-free housing

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Building regulations vary between each of Germany’s 16 states and among municipalities, resulting in an ever-growing patchwork of rules governing everything from the number of electric sockets per room to the shape and color of roofs.

The Construction Ministry estimates its legislative amendment, to be passed by the Bundestag in the fall, will save companies, citizens and local authorities around €2.5 billion ($2.9 billion) annually.

An ‘opportunity,’ not an overnight fix

Tim-Oliver Müller, the managing director of the Federal Association of the German Construction Industry (HDB), said he welcomed the government’s plans but warned that housing construction “would not pick up again overnight.”

“The law alone will not result in a single new apartment, but it will make it easier for local authorities to approve them,” Müller told DW.

He said a “melange of crises” has hit Germany’s construction industry, largely as a result of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, rising energy prices, the increased cost of materials such as concrete and steel, inflation and a jump in interest rates from below 1% to between 3% and 4%.

Müller is convinced that the new changes to the law would not reduce quality standards — for example, those regarding fire safety and structural integrity, which remain in place.

The new legislation is “purely a creation of possibilities, for example, with regard to building extensions or changing the designation of land from commercial to residential, something that was not previously possible,” Müller explained.

#DailyDrone: Berlin Modernist housing estates

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

A lot of hot air?

Environmentalists have expressed concern about easing planning regulations because they fear green spaces will be built on as new development projects are waved through with less time for local residents to object.

“Only with green spaces can we buffer [heatwaves]. Because these green spaces provide active cooling,” Stefan Petzold from the nature conservation association NABU told ARD.

Another person concerned about hot air is Matthias Günther, the head of the Pestel Institute, which researches areas like the economy and housing for the public and private sectors. He described the new legislation as “a lot of hot air” that will “not achieve anything in the short term.”

“Additional paragraphs and sections will be added to the Building Code, creating more bureaucracy. Some things will require the municipality’s consent, and, especially when it comes to building, they often have problems getting a majority because there’s always someone who doesn’t want it,” Günther told DW.

He says that Germany really needs an economic stimulus package for housing construction starting in the fall, accompanied by a loan program with interest rates fixed at 2% for the next 20 years.

“The city would essentially pass on its more favorable credit conditions. It wouldn’t cost that much. Everyone I talk to says that if they could get financing at 2% then they would start building again,” economist Matthias Günther believes, adding that a similar scheme had already proven successful in Poland.

Accommodation, food and EVs — MADE

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Too few homes and fewer solutions

The desperate lack of housing is one of the main reasons why rents have been exploding in big German cities, says Bernard Faller from the Federal Association for Housing and Urban Development (VHW). More than half Germany’s population lives in rented accommodation, the highest share in the European Union.

While Germany has some of the strongest tenant protection laws in the world, Faller said those laws serve to protect existing tenants and work against those who want or need to move, particularly young people and large families. “The problem remains the same: there are too few homes to meet demand,” he told DW.

The construction turbo plans are a “very exciting experiment,” according to Faller.

“Until we come up with something better, and I can’t think of anything better, the key to easing the overheated housing market, to curbing rising rents, is for more affordable housing to be built,” he said.

According to the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR), Germany will need approximately 320,000 new homes every year until 2030.

The previous federal government, which lost its majority in the February 2025 election, promised to build 400,000 homes annually. But by 2024, that figure was just 251,900, 14.4% down on the previous year.

The new coalition of the center-right bloc of Christian Democrats and Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and center-left Social Democrats (SPD) is planning to boost the Construction Ministry’s budget for 2025 to €7.4 billion in 2025 from €6.7 billion the previous year.

This money will be invested in the construction of social housing — subsidized apartments for low-income families, projects for climate-friendly construction, turning commercial areas into residential areas and promoting homeownership for young families.

Edited by Rina Goldenberg

While you’re here: Every Tuesday, DW editors round up what is happening in German politics and society. You can sign up here for the weekly email newsletter, Berlin Briefing.