The Productivity Commission says “tough-on-crime” policies are directly undermining Closing the Gap targets, as the latest annual data shows rates of adult incarceration continue to worsen and youth detention rates soar in parts of the country.

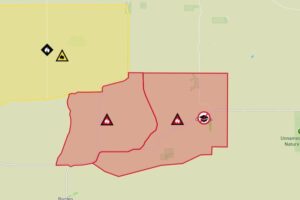

The data also shows the Northern Territory is the worst-performing jurisdiction in the country, with the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people going backwards on eight targets, including youth detention and adult incarceration.

Nationally, only four out of the 19 targets are on track to be met by the deadline of 2031.

BushMob is one of the few rehabilitation centres in Alice Springs for young people. (ABC News: Xavier Martin)

Since winning government in 2024, the Northern Territory has lowered the age of criminal responsibility from 12 to 10 and introduced tougher bail laws and police search powers.

Productivity Commissioner and Gungarri man Selwyn Button said its “tough-on-crime” approach has shown up in the annual Closing the Gap data.

“There is an absolute direct correlation between the two,” he told the ABC’s Indigenous Affairs Team.

“We certainly can see the direct correlation between the legislative change in the Northern Territory to the direct outcomes in terms of increasing numbers of incarceration rates.”

Mr Button is urging the government to invest in prevention programs over punitive approaches to youth justice. (ABC News)

Advocates and researchers are calling on governments to avoid punitive approaches and invest in holistic solutions that address root causes like poverty, health and housing.

“You can’t actually arrest your way out of an issue,” said Mr Button.

“What we’re asking governments to think about is what early intervention programs you can design … so that our young people aren’t ending up in the criminal justice system to just determine a criminalised response to dealing with a social issue.”

Young people needing help ‘don’t know where to go’

Deep in the red centre of Australia, one community organisation is helping children as young as 10 years old connect with their culture and get help.

BushMob is an Aboriginal community-controlled alcohol and drug rehabilitation program based in Mpartnwe/Alice Springs, and has been a safe place for many young people for more than two decades.

It provides cultural and therapeutic programs, including on-country bush camps, horse therapy, counselling, and support linking in with services.

“The young people talk about connection to culture, feeling their place within it, feeling the connection to something other than the systems that they’re seeing day to day,” said BushMob CEO, Jock MacGregor.

Mr MacGregor said BushMob gives young people space and connection to heal and “quiet time to think”. (ABC News: Xavier Martin)

For over 16 years, Mr MacGregor has seen many young children come through the doors, some compelled by court orders and others who admit themselves by choice.

“When I talk to young people about what’s going on with life … They feel like there’s no choice, they feel like there’s no support,” Mr MacGregor said.

“They feel very isolated and if they want to get help, [they don’t] know where to go.”

The Australian Human Rights Commission has long called for greater investment in early intervention and diversion programs such as BushMob’s.

Its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Katie Kiss said the Northern Territory’s current approach “is ignoring all the expert advice that they’re receiving”.

“[Going backwards on] each of those targets that are under the Closing the Gap agreement represents a human rights violation,” she said.

Ms Kiss said the NT government’s actions were going against their Closing the Gap targets. (ABC News: Mark Leonardi)

This week, the Finocchiaro government has introduced another round of sweeping changes to its Youth Justice Act.

They include:

Access to a young person’s criminal history when it comes to sentencing for adult offencesRemoving “detention as a last resort”Reinstating spit hoods and stronger powers around “reasonable force”Expanding the powers of the Commissioner to manage emergencies

In a statement, the NT government said the new laws were a response to “repeated community concerns” and cases where young people reoffended while on bail.

“Territorians have a right to safe streets and communities, victims have a right to a responsible justice system, and serious offenders have the right to remain silent,” Corrections Minister Gerard Maley said.

The new laws came in the same week the ABC reported nearly 400 Indigenous children were held in NT police watch houses over a six-month period, during which time there were nearly 20 incidents of self-harm involving children.

The ABC has sought comment from the NT government on the latest Closing the Gap data.

National snapshot on Closing the Gap

The Productivity Commission report shows the four targets on track to be met by 2031 include pre-school program enrolments, employment, and land and sea rights.

As reported in March, the rate of babies born at a healthy weight was no longer on track to be met.

In a statement, Minister for Indigenous Australians Malarndirri McCarthy said while some progress had been made, more work needed to be done.

“I am pleased that nationally we are seeing improvements in 10 of the 15 targets with data,” she said.

“However, it is very concerning that we are still seeing outcomes worsening for incarceration rates, children in out-of-home care and suicide.

“It’s important that state and territory governments all back in their commitments under the National Agreement with actions that will help improve outcomes for First Nations people.”

Along with the NT, Queensland and the ACT are also going backwards on their commitment to reduce the rate of young people in jail by 30 per cent by 2031.

While the 2023/24 rate of youth incarceration has increased nationally from the previous four years, the overall trend shows no change from the baseline year of 2018/19.

The report also found more than one-third of kids in youth detention last year first entered the system when they were 10–13 years old.

The Commission’s latest report comes as the number of First Nations people who have died in police or prison custody exceeds 600 deaths since a landmark royal commission handed down recommendations in 1991.