This article mentions child sexual abuse.

The story that won’t die — the sex trafficking and money laundering of American financier and child sex offender Jeffrey Epstein — is telling us a lot about the intersection of high finance and the elites who circulate through it.

But from where has this renewed focus emerged? Most of the controversial events coming to light occurred more than two decades ago. Even now, Donald Trump is trying to explain away his apparent outrage at Epstein having “stolen” then 16-year-old Virginia Giuffre from his Mar-a-Lago spa in 2000.

The short answer is journalism, particularly the shift in how journalists regard news and sources following The New York Times‘ breaking of the Harvey Weinstein scandal in 2017. Case-by-case reporting of violence and abuse had been slowly making the subject newsworthy when the NYT re-launched it with the “believe women” #MeToo foundation, poking at that ugly spot where gender and power mesh in systemic patterns of sexual abuse and violence.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1215501

In the case of Epstein, it was the hard grind of tracking the story from victim to victim, particularly by the Miami Herald’s Julie K. Brown in 2018, nearly a decade after the law had washed its hands of the case with a soft plea deal that protected Epstein from further prosecution.

It paid off. “If not for Miami Herald reporter Julie K. Brown, we might never have learned anything about Jeffrey Epstein’s sex trafficking operation, its implication of wealthy, powerful, influential men, and the existence of massive files documenting all of it,” Jennifer Rubin wrote in her newsletter last month.

(A conservative never-Trumper and recent refugee from Jeff Bezos’ Washington Post, Rubin wrote the now perhaps overly optimistic Resistance: How Women Saved Democracy from Donald Trump about how the US president enraged and engaged American women in his first term.)

The journalistically obvious (in retrospect) “believe women” gambit requires flipping traditional journalistic guidelines that treat important men as trustworthy as sources, with any doubts hidden in the defensive crouch of direct quotes and a shrugging “well, that’s what he said.”

In her Meditations in an Emergency newsletter, Rebecca Solnit wrote this week: “One reason this violence is so unacknowledged is that it is in the most literal sense not news — there are tides of hatred and violence against other groups that ebb and flow, but violence against women is global and enduring, a constant rather than an event.”

This shift in coverage leans into that volume, making abuse news by piling up testimonies from abused women to cancel out the weight of the untested word of a handful of “respectable” gentlemen. Powerlessness, through its sheer scale, can overwhelm elite power.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1214681

It’s harder than it looks, relying on an ethics of care that approaches traumatised sources with a sensitivity that many (particularly male) journalists struggle with.

We’ve seen how it works here in Australia, too. News Corp initially treated #MeToo as just another opportunity for sleazy celebrity gossip, while Australian media got its moment when the ABC’s Louise Milligan brought the intensity of the “believe women” gaze to Canberra’s Parliament House culture in late 2020 and early 2021, triggering (among many other things) the flight of Liberal women from the Liberal Party.

When Julie K. Brown started her work, the Epstein moment seemed safely in the rear-view mirror. The Bush-appointed US attorney who struck the plea deal, Alexander Acosta, was in the Trump cabinet as labor secretary. To the extent that “Epstein” was a thing, it was a fringe meme in the fringest corners of the online conspiracy web.

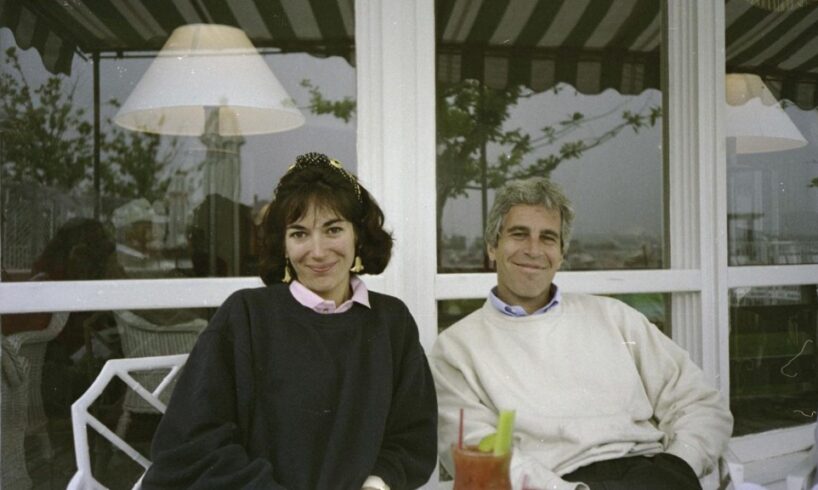

Brown finished with the rarest of things: reporting so shaming that it forced a Trump cabinet minister to resign. It led to the high-profile break-up of at least one billionaire marriage — Bill and Melissa Gates. Once-strutting masters of the financial universe were forced out when indiscreet connections turned up. Epstein was arrested and charged, and would die in prison (in increasingly mysterious circumstances). His accomplice in the trafficking, Ghislaine Maxwell, has been jailed.

Most importantly, the story gave a voice to the victims, identifying about 80 women — many from low-income or unstable homes — who say they were molested as teenagers. They talked, too, of underage girls trafficked from Europe, Ecuador and Brazil. Fox News is reporting that more than 1,000 women and girls may have been involved.

Yet this sort of deep-dive reporting that gives a voice to victims has a weakness: it depends on resources, impact and legal clout, as well as a news media model increasingly under stress.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1214186

The Miami Herald — long one of America’s most significant mastheads — is much weaker than it was when it broke the Epstein story. Its parent company, McClatchy, was bought out by a hedge fund, Chatham Asset Management, in 2020. Most US mastheads are now held in bottom-line-oriented hedge fund chains, and the Miami Herald newsroom has faced repeat redundancies.

The Trump environment, too, has made it harder. In an interview this week with Kara Swisher, Brown said that Trump’s running commentary (and the suggestion he may pardon Maxwell) has made most of the victims fearful about speaking out.

Meanwhile, Brown and other reporters are turning to another resource-hungry innovation: following the money. Epstein has already turned up in large dumps of financial data mediated through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Expect the most interesting stories about money, power and abuse to come out of that angle.