Australia’s biggest radiology provider giving at least 30 million medical scans of Australian patients to an AI company, without their knowledge or consent, did not appear to breach Australia’s privacy rules, the regulator has found.

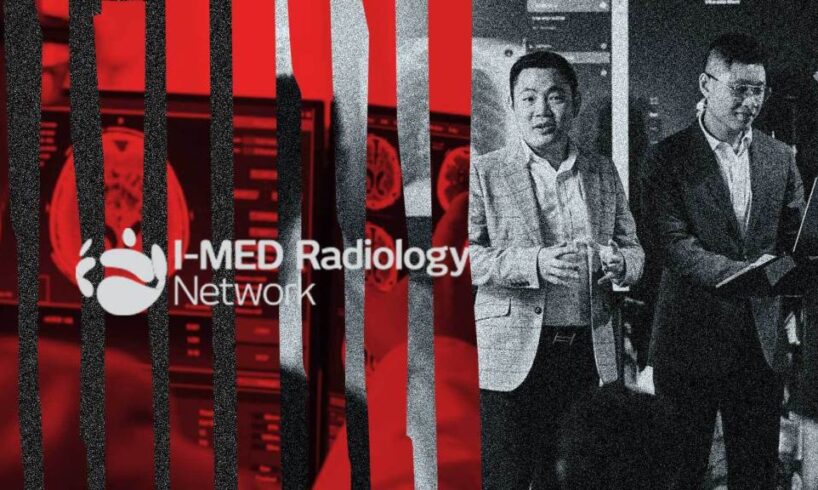

Last year, a Crikey investigation uncovered that I-MED had given millions of patient X-rays, CT scans and other scans to buzzy Australian health tech company harrison.ai to train its AI models.

Our reporting prompted preliminary inquiries from the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) into I-MED and the disclosure of these scans to harrison.ai (which I-MED took an ownership stake in).

The OAIC announced on Thursday afternoon that privacy commissioner Carly Kind would close the investigation after being satisfied that I-MED’s data had been “de-identified sufficiently”. She found this despite a “small number of instances” where the company had accidentally provided non-anonymised information.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1175720

OAIC published the results of the inquiries in consultation with I-MED, harrison.ai and sister company annalise.ai, and said the company’s de-identification of the data was a “case study of good privacy practice”.

The inquiries confirmed for the first time the scale of the operation and the lack of awareness of patients. The report says: “I-MED shared less than 30 million patient studies (a study refers to a complete imaging session for a single patient and may include multiple image types, that together represent a single diagnostic episode)”.

It also established that “patients whose data was provided to annalise.ai were not notified of this use or disclosure and did not provide their consent”.

Know something more about this story?

Contact Cam Wilson securely via Signal using the username @cmw.69. Or use our Tip Off form.

The crux of the privacy commissioner’s inquiries was whether the scans were legally “health information”, a special class of protected data, when handed by I-MED to harrison.ai.

I-MED said it had de-identified the data by removing names associated with scans and any text on the scan images, as well as via other steps. This, it said, meant the patient would no longer be “reasonably identifiable” and therefore the data would no longer be considered health information.

Kind was satisfied that this was done, other than in a “very small” number of cases where public information had been erroneously shared, and thus I-MED did not breach protections for health data, although she did leave the door open for further inquiries.

“It is still open to the commissioner to commence an investigation of I-MED with respect to these or other practices, and this case study should not be taken as an endorsement of I-MED’s acts or practices or an assurance of their broader compliance with the [Australian Privacy Principles],” the report said.

The report did not address the use of the data given by I-MED, only its handover.

An I-MED spokesperson directed Crikey to a public statement welcoming Kind’s report, that stated, “As the regulatory landscape evolves, we remain committed to the highest standards of privacy and compliance, while continuing to innovate in ways that improve patient outcomes and system integrity.”

Earlier this year, the federal government became a major shareholder in harrison.ai with a $32 million investment via the National Reconstruction Fund. I-MED has since quietly begun asking customers for consent to use their scans to train AI.