The child stands at the centre of the market square and stretches forth a finger to the actions of men and the pointlessness of human toil. Rising before that finger is a protruding shadow, that of the child, pointing back to prophesy: “You, too, will toil and labour. It is the inescapable human curse.” Every person, then, lives with a two-edged tragedy: our own share of life’s troubles, meted out to each of us at birth, and the tragic probability of experiencing the disasters suffered by those who were here before us.

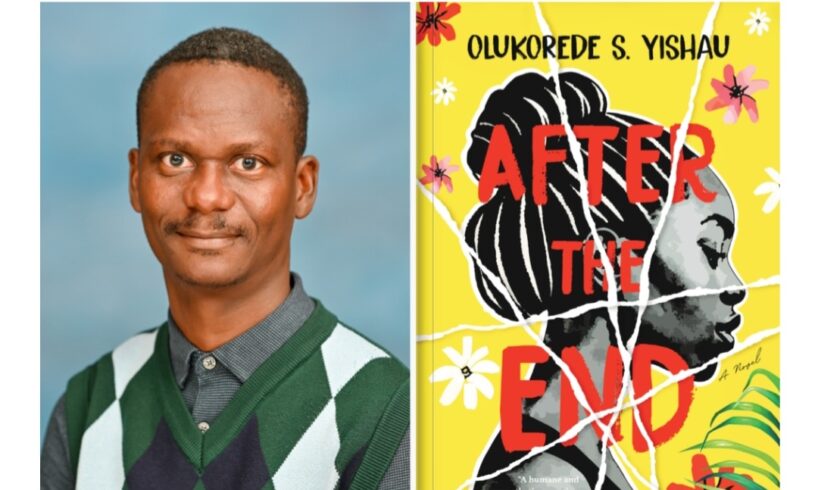

This latter realisation, that over our heads looms the potential doom of repeating the mistakes of the past, which we tend to condemn without empathy or careful inner reflection, dawns on Olukorede S. Yishau’s characters in his 2024 novel, After The End.

The story revolves on the marriage of Idera and Demola, a Nigerian immigrant couple living in the United Kingdom with their three children. When we meet this family, Demola is dead, and Idera, in the grip of grief’s vice-like hold, is visited by his previously unknown first wife Lydia and her son. This visit shatters the foundation of everything she believes and plunges her into the worst kind of disillusionment: one in which the illusion was the only reality ever known.

The widowed Idera navigates raising three growing boys in a politically unstable society rife with racial discrimination, economic uncertainty, and social decay, while nursing a grief worsened by the deep sting of her late husband’s betrayal. The story, though clichéd — woman loses husband, becomes a single mother, suffers greatly, meets an old lover, remarries, and finds a well-deserved happy ending — triumphs as a sociological novel because of the author’s careful attention to the complexity and fragility of lived human experience(s). A complexity that seems simple to the outsider; one that might even prompt an observer to exclaim, “Oh, fool, just make a sound judgement and escape this mess!” Yet, to the experiencer, this complexity is made more complicated by unaddressed trauma and a judgement clouded with fragments of fear, guilt, lust, and more.

Because the dead cannot speak, Demola’s perspective is chronicled by an external, limited, omniscient narrator, a technique that provides insight into his childhood and the circumstances of his upbringing (all factors that shape his mindset, actions, and decisions). This approach also offers a degree of objectivity, because it places the reins of judgement in the hands of readers and gives a panoramic view of Demola’s apparent and psychological realities, enabling us to question the concept of fate versus decision-driven consequences.

Are we truly doomed to repeat the mistakes we once condemned, or does it ultimately hinge on the choices we make at life’s maze-like crossroads? This question, coupled with the dramatic presentation of significant events in Demola’s life, told through a non-linear narrative structure, and interwoven with the stories of other characters before and during his marriages to Lydia and Idera, forms some of the fundamental ingredients that make the novel a page-turner.

It may seem repetitive to note that this novel is rich with material for psychoanalytical criticism. For although it is fast-paced, with a realism and simplicity of language reminiscent of a kitchen-sink play, it is also laden with the emotional weight and intensity that arise from the deeply multilayered nature of the mind as a force that propels or nudges a person into unforeseen circumstances.

On page 201, Idera confesses to her first love, “I’ve been married before, Justus. The first time, I was so relieved to be asked, I just made a lot of assumptions about why he was proposing to me…” a statement that reveals years of deeply ingrained, initially subconscious feelings of worthlessness stemming from being born out of wedlock, abandoned by her father, and later becoming pregnant in similar circumstances. Demola, however, is not fortunate enough to have the opportunity for mental reawakening, and lives all his life with the repressed fear of becoming like his father. Tragically, he repeats the mistakes of his father’s life, including the very betrayal he sought to avoid, and dies bewildered and burdened with the emotional demands of a deceit-ridden polygamy.

The socio-cultural context of this novel greatly influences the experiences of its characters. Issues like the effects of Babangida’s Structural Adjustment Programme in the 1980s; the brutality of Sani Abacha’s regime; the worrying reality of human capital flight in Nigeria, known as Japa; the decay of humanity and disintegration of families in contemporary English metropolises, provide a vital backdrop to the novel’s setting of place and time, and cements its place within the corpus of contemporary Nigerian fiction that mirrors the intricacies of the modern Nigerian experience.

Overall, the story’s movement is toned by an intense interplay of trauma and resilience, setting an expectation for a resolution that respects the gradual, introspective journey to recovery, particularly for Idera. However, its conclusion is somewhat unexpected, because it shifts focus to a romantic reunion between Idera and Justus, as though romance is the pinnacle of her healing. This shift, however moving and exciting, oversimplifies her painstaking path to healing, and closes the narrative on a note less introspective than the story’s earlier depth. In addition, readers should consider the vivid descriptions of sexual activities, which may be unsuitable for those under 18, despite the significance of the issues the work addresses for both teens and adults.

In conclusion, Olukorede S. Yishau’s After The End excels as an artistic venture crafted with careful attention to the layered texture of the human experience. In its exploration of pain and healing, readers are invited to empathise with the characters’ struggles and growth. This novel stands as a triumph of art’s role in observing, commenting on, understanding, and interpreting the human condition.

Joy Eseosa Matthew, a student of (English Arts) at the English Language department of the University of Lagos, is joint winner of the prize for the review of After The End at Reading Cafe’s 10th anniversary celebration.