In an effort to combat falling birthrates, China’s central government has announced a plan to provide families with annual cash subsidies of 3,600 yuan per child under the age of three. Ninety percent of the funding will reportedly come from central government coffers, but the program will be administered and disbursed by local governments.

At Bloomberg, Karoline Kan reported on the details and likely effects of the subsidies:

The government will spend 3,600 yuan ($502) a year per child under age three, according to the official Xinhua News Agency. The assistance, effective retrospectively from Jan. 1 this year and available regardless of the first-, second- or third-child, is meant as an incentive for young couples wary of rising costs of child-rearing.

The policy is expected to benefit more than 20 million families each year, Xinhua reported. China has previously offered tax breaks and has been working to offer more affordable daycare services, it said.

The latest measure follows China’s population shrinking for a third straight year in 2024. New births at 9.54 million last year was only half of the 18.8 million registered in 2016 when China lifted its one-child policy. [Source]

At CNN, Nectar Gan provided historical detail on China’s history of family planning, examples of previous local efforts to raise birthrates, and reactions by experts and the general public to the announced subsidies:

“It’s no longer just a local experiment. It’s a signal that the government sees the birth rate crisis as urgent and national,” said Emma Zang, a demographer and sociology professor at Yale University. “The message is clear: we’re not just telling you to have babies, we are finally putting some money on the table.”

The new scheme, which also offers partial subsidies for children under three born prior to 2025, has been welcomed by eligible parents but Zang said it’s unlikely to move the needle on fertility rate. Similar policies have largely failed to boost births in other East Asian societies like Japan and South Korea, she added.

[…] The irony of the shift from fining parents for unsanctioned births to subsidizing them to have more children is not lost on China’s millennials and Gen Zs – especially those who have witnessed the harsh penalties of the one-child policy firsthand.

On Chinese social media, some users have posted photos of old receipts showing the fines their parents once paid for giving birth to them or their siblings. [Source]

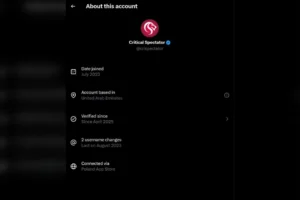

The new policy quickly became a trending topic on Chinese social media, and hashtags such as “3,600 yuan annual subsidy for children under three years old,” “childcare subsidy,” and “childcare subsidy plan released” garnered over 100 million views. It prompted heated discussions on Weibo, RedNote (Xiaohongshu), X, and other social-media platforms, and was the subject of many articles and essays.

CDT Chinese editors have archived five recent articles and essays about the subsidies. An article from Fengsheng OPINION noted that many people seemed “unappreciative” of the subsidies, and suggested three reasons for this: past local subsidies that have raised the public’s expectations; the high cost of raising children in China; and cash aid being framed as helping to “stimulate consumption” as opposed to helping families. A piece from WeChat account Norway TALK compared the rapid decline of China’s birthrate with the more gradual declines experienced by Japan and South Korea, and expressed skepticism that the recently announced Chinese subsidies will make much of a dent. The author also described some of the broader policy measures to promote childbirth in Japan and South Korea, and predicted that China would eventually follow suit. Another WeChat piece in a similar vein discussed how generous cash transfers, tax incentives, subsidized childcare, and family-leave policies in Japan, South Korea, and Northern Europe haven’t managed to increase birthrates by much (with France faring only slightly better). The author concluded that while the 3,600 yuan annual subsidy is a good start, China’s demographic challenges call for a broader range of socioeconomic support and policy tools.

Another archived piece is a powerful personal essay from Jin Qiqi about growing up in a family of four children during China’s “one-child policy” era. Jin writes about how she and her sister were left behind with their grandparents in the countryside, and about the punishments meted out to her parents—fines, confiscation of livestock, and eventually, demolition of their house—for repeatedly violating family planning rules. Her conclusion is that every generation has had to contend with meddling and impediments in their reproductive lives:

Our parents’ generation wanted to have children but were held back by government policy; for our generation, the policies have been relaxed, but we are still held back by life.

History always repeats itself. Where once the government forbade people from having kids, it is now trying to convince them to have more kids. Things have come full circle, and we’re right back where we began.

But I will always carry the memory of how the Family Planning Office ripped the tiles from our rooftop and smashed the wooden walls of our house. It is a reminder that the seemingly simple choice of whether or not to have children is never just about money. [Chinese]

CDT Chinese editors have also compiled a selection of comments from Chinese social media. The general tone was supportive of the subsidies, but many commenters expressed reservations about whether the subsidies were adequate or timely enough, about the fiscal constraints of local governments, and about whether the subsidies would be accessible to all, including migrant workers and their children. Some commenters described the subsidies as a way to “fertilize the chives”—in other words, to provide just enough sustenance to create a new generation of exploitable workers. A selection of comments are translated below:

朱海峤医生: As long as you’re willing to have kids, the government will provide subsidies. // 陆人壬: They’re only giving subsidies because people aren’t having kids.

闷闷西瓜: If everyone kept refusing to have kids, they’d raise the subsidy to 600 per month.

yjingnn8: It’s too little, too late, and won’t solve the population crisis.

gozh362598: They’re running out of chives, so they’ve finally started giving us more “fertilizer.” It took a crisis to make them act.

John39336763524: The truth is, these recent subsidies for home appliance purchases and childcare are a rare [government] effort to “fertilize the chives.” They’re realizing that if the chives are stunted, it’ll wipe out their “harvest.”

lee065083: With local finances already stretched to the limit, I’m curious where the money will come from.

倔强不屈的不配: Will localities actually be willing to disburse the funds?

unreaI233: It’s better than nothing, and at least they’re paying attention to the problem.

forever小猪饲养员: 3600 a month would be more like it. What can you do with just 300 a month?

足球丨往事: Seems like they’re not too worried, since the subsidy only pays for about one can of powdered formula per month.

还能再拖一会: This pittance won’t change the minds of those who don’t want kids, but those who do have kids will be marginally better off.

pycynthia: Is raising kids only a three-year project?

ooO樂濤濤Ooo: Are they going to refund all the “social maintenance fees” [a euphemism for fines] paid by people who exceeded childbirth quotas back in the day?

10__ManUtd: This is too radical. They should first subsidize single people, then married couples, and finally those who have kids. Without subsidizing the first two groups, it’s pointless to try to subsidize the latter.

懿萌懿千秋: This year our locality announced a new policy, and we’ll see whether they can implement it before the year’s end. We kids of migrant workers [living in cities where they lack residence permits] are annoyed because we can’t benefit from these various policies. We haven’t heard anything from the local authorities back in our hometown, but we don’t really belong where we’re living now, either.

浦东外高桥: It’s a drop in the bucket and they’re just milking it for publicity.

郑小海同学: For ordinary people, free medical care is the most vital form of subsidy. These days, it’s a struggle just to survive!

肥儿飞翔: Lamborghini coupons [Refers to a 2021 Alipay promotion offering five yuan off the purchase of a Lamborghini; nowadays, it implies that something is worthless.] [Chinese]