Kabuki was believed to have been created in the 17th century and hasn’t stopped evolving for the past 400 years, especially when it comes to its stories. The classics written during the Edo period are still the most popular, but new plays are being written all the time. In 2009, for instance, the dramatist Kankuro Kudo wrote Oedo Living Dead, a kabuki tale about zombies in feudal Japan.

It was briefly screened in early July this year as part of the Cinema Kabuki initiative that brings filmed kabuki performances to movie theaters. Almost every day of the limited run, the cinemas were packed with curious audiences, probably because zombies are almost never seen in kabuki. Actually, they are rarely seen in all forms of Japanese pop culture.

Poster for “Oedo Living Dead” | Cinema Kabuki

Night of the Laughing Dead

Even if you haven’t seen any of the trailers and went into Oedo Living Dead with no expectations, the play makes it clear what kind of story it is within the first few seconds by introducing two actors in fish costumes playing kusaya and complaining about their smell. Kusaya are fermented fish from the Izu Islands characterized by their overwhelmingly pungent aroma.

The story then segues into the kusaya sauce used by the vendor Oyo, bringing the dead to life and the enterprising Hansuke using the same sauce to put the zombies to work, since they won’t bite a living human slathered in the stinky concoction. The play then becomes a commentary on the exploitation of Japanese temp workers.

It’s a satirical comedy that has its darker moments. During one scene, when dozens of zombies suddenly push their undead hands through a shoji screen, you realize the story could have worked as a straight-up horror.

“Zombies in feudal Japan” is a cool premise that would’ve been additionally aided by the creatively gory makeup used in the play. So why did Kankuro Kudo go with a humorous take? And why do so many Japanese productions, from kabuki to live-action movies and anime, treat zombies as comedic fodder?

Still from Tokyo Zombie (2005) | IMDB

Zombies Might Be Too Foreign for Japan

Tokyo Zombie, released in 2005, deals with a zombie apocalypse but approaches the topic as a joke, like when one of the main characters thinks he becomes undead after being bitten but is actually fine because he was attacked by a zombie with dentures.

The Zom 100: Bucket List of the Dead (2023) anime features a more end-of-the-world horror setting but is ultimately an uplifting tale about going out into the world and doing everything you ever wanted to do because tomorrow is not promised. Then there’s Battlefield Baseball (Jigoku Koshien), released in 2003, about undead baseball.

While there are many examples of Japan treating zombies as serious threats, like in the Resident Evil video games, they are usually set in the West and feature foreign protagonists.

That’s part of the reason why Japan doesn’t really seem to fear zombies. They look at the idea as a Western invention that’s a bit too silly to be scary. Japan takes horror very seriously, and in Japanese horror, the malevolent force is often connected to nature and clashes with some aspect of modernity.

No matter how fantastical the premise, Japanese horror tends to rely on familiar elements that get twisted into something sinister, like a VHS tape being a harbinger of death in The Ring. Corpses simply aren’t part of everyday life in Japan.

Not that people don’t die here, but, after they do, they usually get cremated, with the country only having a handful of Western-style cemeteries where reanimate-able bodies are put in the ground.

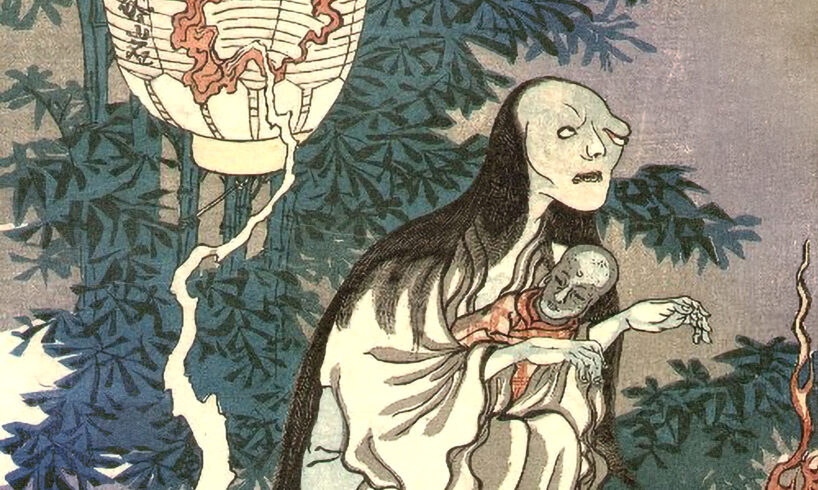

Depiction of vengeful Onryo spirit by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (c.1836)

Japanese Monsters vs. Western Zombies

That isn’t to suggest that Japan is unafraid of the undead. They can be found everywhere, including in kabuki, folklore, mythology, legends and more. But they are very different from Western zombies.

When the dead come back to life in Japan, they usually do it in the form of an onryo avenging ghost (typically of a mistreated woman) or a yokai supernatural creature. Both of them often straddle the border between the physical and the spectral world. Though not always there corporally, they still interact with the world of the living, or become corporeal through intense emotions.

On the whole, though, Japanese monsters tend to be less biological. Even Godzilla was once portrayed as a supernatural creature in the movie Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack, when he was possessed by the ghosts of those who died in World War II. Zombies are, by definition, almost entirely biological and that already puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to scaring Japanese audiences.

Hone Onna (Bone Women) are the reanimated remains of women who died with intense feelings of love that they continue to seek beyond the grave. Appearing to potential lovers as living and in their prime, these creatures spend night after night with their unwittingly necrophiliac lovers, sapping their life force away until the victim dies. Yama-uba, meanwhile, are cannibalistic yokai mountain witches with bulletproof skin, knife teeth and a second mouth on the tops of their heads.

It’s true that zombies have numbers on their side, but Japanese paranormal monsters also come in bulk. When hundreds-to-thousands of different yokai and oni demons parade through the streets, it’s called the Hyakki Yagyo, a motif that has been appearing in Japanese art for centuries. In such a culture, it’s a little hard to take zombies seriously as horror antagonists.

Discover Tokyo, Every Week

Get the city’s best stories, under-the-radar spots and exclusive invites delivered straight to your inbox.