(Analysis) In mid-August 2025, the United States widened its campaign against Brazil’s government, moving from sanctioning members of the judiciary to targeting officials in the health sector.

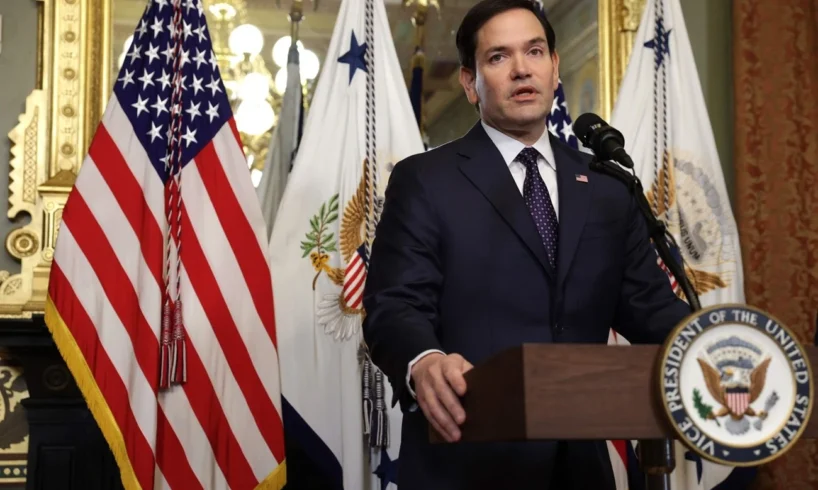

On August 13, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced visa cancellations for “several members” of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration.

The focus: those tied to the Mais Médicos program, which places doctors in underserved areas of Brazil, including rural and remote communities.

Washington accuses the program of acting as a “forced labor” export scheme from Cuba, enriching Havana while circumventing U.S. sanctions.

Two names were made public: Mozart Júlio Tabosa Sales, Health Ministry secretary, and Alberto Kleiman, a former ministry advisor and ex-official of the Pan American Health Organization (OPAS). The bans also extend to some family members.

Rubio claimed Mais Médicos was “an inconceivable diplomatic coup” by the Cuban regime, facilitated by Brazil and OPAS, in which Cuban doctors were sent abroad under contracts that diverted a large share of their salaries to Havana.

Washington Turns Up the Heat on Brazil — Echoes of Venezuela in Sanctions from Judges to Health Officials. (Photo Internet reproduction)

The U.S. position is that this violates both human rights norms and existing sanctions against Cuba. Brazil’s government has pushed back hard.

Health Minister Alexandre Padilha said the accusations were baseless, calling the measures “unjustifiable attacks” on a program that “saves lives and is approved by those who matter most: the Brazilian people.”

Mozart Sales called the sanctions “unfair” and defended Mais Médicos as part of the public healthcare system’s mission to bring essential services to those who would otherwise go without.

The Precedent: Targeting Brazil’s Supreme Court

The August sanctions did not come out of nowhere. In July 2025, Washington took the extraordinary step of directly targeting Brazil’s judiciary.

Justice Alexandre de Moraes, a central figure in investigations into former president Jair Bolsonaro and the January 8, 2023 riot, had his U.S. visa revoked.

He was also sanctioned under the Global Magnitsky Act, a tool usually aimed at officials from authoritarian regimes accused of human rights violations. Several of his Supreme Court colleagues also lost their visas.

The sanctions froze any assets under U.S. jurisdiction and prohibited American companies from doing business with Moraes.

While he reportedly holds no U.S. assets, the sanctions are symbolically heavy and practically inconvenient — potentially affecting even his ability to use international credit systems linked to U.S. banks.

The focus: those tied to the Mais Médicos program, which places doctors in underserved areas of Brazil, including rural and remote communities.

President Donald Trump, in his second term, escalated further. He imposed steep tariffs on Brazilian steel and other exports, explicitly linking them to the prosecution of Bolsonaro.

The message was clear: stop pursuing Bolsonaro or face economic consequences. Brazilian law, however, gives no mechanism for the executive to halt a Supreme Court trial.

Eduardo Bolsonaro’s Washington Campaign

Much of the pressure stems from active lobbying by Bolsonaro’s allies, especially his son Eduardo Bolsonaro.

Having relocated to the U.S. earlier in 2025, Eduardo has built ties with Trump’s inner circle and openly pushed for sanctions on officials tied to his father’s legal troubles.

After the Moraes sanctions, Eduardo celebrated publicly, saying Trump’s measures would “contain and punish authoritarian regimes” like the one “Lula and Moraes are turning Brazil into.”

Moraes, from the bench, accused Brazilian “traitors” of conspiring with a foreign power to destabilize the country, trigger an economic crisis, and pave the way for another coup attempt.

How the U.S. Targeted Venezuela (2017–2020)

The pattern in Brazil echoes the strategy used by the U.S. against Nicolás Maduro’s Venezuela:

2017 – Sanctions on Supreme Court justices after they stripped the opposition-led National Assembly of power.

2017–2018 – Sanctions on ministers, electoral officials, and military leaders for undermining democracy.

2017 onward – Visa bans for hundreds of officials and relatives; by March 2019, over 600 visas revoked; by 2020, more than 700 individuals affected.

2019 – Recognition of opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president; coordination with allies in the Lima Group and OAS to isolate Maduro.

2019–2020 – Economic sanctions on oil company PDVSA, blocking Venezuela’s main revenue; August 2019 embargo on all Venezuelan state assets in U.S. jurisdiction.

2020 – U.S. indictments against Maduro and aides on drug trafficking and terrorism charges; bounty of $15–25 million on Maduro’s capture.

This multi-pronged strategy—personal sanctions, travel bans, economic warfare, and international isolation—left Venezuela economically shattered and diplomatically cut off, though Maduro remained in power with military and foreign backing.

Patterns Repeating in Brazil

In both Venezuela then and Brazil now, Washington has:

Used personal sanctions and visa bans to pressure key officials.

Aligned with the domestic opposition to push for political change.

Applied economic tools—from sanctions to tariffs—as leverage.

Framed the government as authoritarian to justify intervention.

The coordination with Eduardo Bolsonaro today mirrors U.S. ties with Venezuelan opposition envoys during the Maduro years.

In both cases, the aim is to weaken the target government from within by isolating it internationally and pressuring its political base.

By 2020, Venezuela was diplomatically isolated and economically crippled — though Maduro remained in power, backed by the military and allies like Russia, China, and Iran.

Brazil and Venezuela: The Similarities

The tactics now appearing in Brazil mirror the Venezuela campaign in several ways:

Brazil and Venezuela: The Similarities

Venezuela (2017–2020)

Brazil (2025)

Sanctions on Supreme Court justices and high officials

Sanctions on Justice Moraes and other STF members

Hundreds of visa revocations for officials and families

Visa cancellations for STF justices, health officials, and families

Coordination with domestic opposition (Guaidó camp)

Coordination with Bolsonaro camp, led by Eduardo Bolsonaro

Economic sanctions (oil, markets)

Tariffs on steel and other exports

Framing regime as authoritarian to justify action

Framing Lula’s government as authoritarian, tied to Cuba

In both cases, Washington works hand-in-hand with local political actors seeking to weaken or unseat the current leadership, using targeted personal sanctions, economic leverage, and international rhetoric.

Key Differences That Could Change the Outcome

Despite the similarities, Brazil is not Venezuela circa 2017.

Economic Scale: Brazil is the 10th largest economy in the world, a G20 member, and a major trading partner to multiple powers.

Democratic Legitimacy: Lula’s government is internationally recognized as democratically elected, unlike Maduro’s disputed 2018 re-election.

Diplomatic Isolation: The Venezuela strategy had broad regional and European support; U.S. moves against Brazil are largely unilateral.

Diversified Trade: Brazil can pivot to China, Europe, and other partners to offset U.S. pressure.

These differences mean full isolation is unlikely, but sustained U.S. economic and political pressure could still create significant strain.

What’s at Stake

The U.S. is applying tools normally aimed at authoritarian regimes — Magnitsky sanctions, personal visa bans, and economic penalties — to a democratic ally. This raises sovereignty concerns and sets a precedent for similar interventions elsewhere.

If the confrontation escalates, Brazil could face:

Expanded U.S. sanctions on other officials or industries.

Greater domestic polarization fueled by foreign involvement.

Closer ties with China, Russia, or other U.S. rivals.

For the U.S., this approach risks alienating Latin America’s largest democracy and undermining its own credibility on supporting democratic norms.

Conclusion: Venezuela’s Shadow

The Venezuela campaign between 2017 and 2020 shows how far the U.S. is willing to go when it labels a government “authoritarian.” Brazil is not there — but the methods now in play are drawn from the same playbook.

Whether Brazil “follows Venezuela into the abyss” depends on two questions: how far Washington is willing to escalate, and how successfully Brasília can rally domestic and international support to resist.