The political landscape is now set for October: La Libertad Avanza (LLA) and Fuerza Patria closed their lists in an orderly fashion and will be the main protagonists of the election campaign.

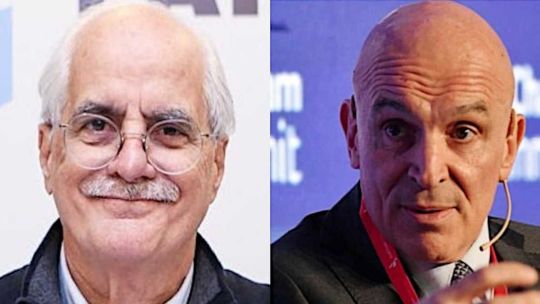

With different profiles, Jorge Taiana and José Luis Espert embody the two poles of polarisation. Outside this framework, each party faces its own challenges: the identity crisis for Mauricio Macri’s camp as it is swallowed up by the libertarians, the fragmentation of the leaderless Radicals and the future facing the centrist governors’ bloc.

Candidates were defined district by district, so speaking of a single closing may be reductive. Still, analysts agree that polarisation will be the organising axis of politics in the months ahead. Although a large segment of the population feels represented by neither Milei nor Peronism, so far – despite the efforts of those centrist governors – no political space has managed to overcome this dichotomy.

In conversation with Perfil, Facundo Nejamkis (Opina Argentina), Cristian Butié (CB Consultora) and Santiago Giorgetta (Proyección Consultores) analysed the outlook for the most competitive political forces heading into the midterms.

La Libertad Avanza: Karina Milei’s construction

Within LLA, Giorgetta highlighted the role of the President’s sister. “Karina Milei closed the lists in a very particular way. It is remarkable how someone with little experience managed to defeat several political caudillos,” he said.

The ruling party’s strategy varied by district. “In some places, like Mendoza or Buenos Aires City, with [candidates] Luis Petri or Patricia Bullrich, LLA are going out to win with well-known figures. But there were surprises in other places, such as in Córdoba with Gonzalo Roca, practically unknown in the local political map. The brand was put ahead of the people,” Butié reflected.

LLA intends to nationalise the campaign and hammer home the slogan used by its provincial candidates in Buenos Aires Province: “Kirchnerismo nunca más” (Kirchnerism never again.”) President Javier Milei will personally lead the drive to the polls.

For Nejamkis, “one of the distinctive features is the institutional power of the Presidency to generate a unified, homogeneous offer nationwide.” He added that while LLA’s slate brought no major surprises, it did demonstrate its ambitions for power and foreshadowed moves for the second stage of Milei’s government. “With Petri we can imagine a candidacy for the Mendoza governorship, because if he wins this election, he’ll have strong chances. And it also creates room to renew the Cabinet,” said the analyst.

The alliance signed by Karina Milei with PRO did not see prominent slots for Macri’s camp on the lists. Nor did the presidential chief-of-staff reward those leaders who had backed the government’s measures in its first phase. “It is clear Milei’s political project has hegemonic ambitions. They are not building an electoral coalition in the style of European parliamentarianism, but something more akin to Peronist construction,” said Nejamkis.

Butié envisages an election similar to 2017, when Juntos por el Cambio won 40.3 percent nationally. “At that time there was talk of Cristina’s comeback and also of stability. A large part of the country was painted yellow and it was thought Macrismo would last 20 years — and we know how that ended. That’s why I believe the result of this election has little to do with what may happen in 2027,” he said.

Fuerza Patria: Consensus candidate

After weeks of internal feuding, Peronism presented a unified list with representation from several different sectors. According to Butié, “unity was a sine qua non condition for survival.” Nejamkis observed that “everyone made sacrifices to achieve unity.” Giorgetta stressed that the bloc “achieved order after a traumatic closing.”

The experts emphasised the role Taiana will now play as the lead candidate for Buenos Aires Province. “His main virtue is that he won’t face friendly fire. He’s a leader with significant internal consensus, but also a figure with an unimpeachable historical record in Peronism,” Giorgetta highlighted.

Taiana’s choice means he will face current deputy and media-savvy economist José Luis Espert. Depending on perspective, this is either a smart move or a challenge.

“One could argue Taiana is a little colourless for a campaign and perhaps not ideal to mobilise Fuerza Patria’s voters. But at the same time he’s a tougher opponent for someone like Espert. It’s easier to insult Máximo Kirchner or Axel Kicillof than Taiana, a man who doesn’t raise his voice and isn’t associated with corruption or scandalous policies,” Nejamkis reflected.

PRO: Secondary role

One of the biggest outcomes of the list-closing was confirmation of the marginalisation of ex-president Mauricio Macri.

According to Butié, “PRO accepted the consequences of the May election [in Buenos Aires City] and its leaders stepped aside.” The analyst says it’s not yet time to speak of the “disappearance” of the yellow party, but of a change of era. “It was once a party with national projection and now is reduced to a local force that must focus on preserving its stronghold in 2027, Buenos Aires City,” he added.

Nejamkis bluntly referred to “the swallowing-up of PRO by LLA” and noted that none of the party’s identity remains in the alliance with the ruling party. “It is striking that one of the spaces so relevant right up to the last election has vanished as a brand – its leaders were not incorporated as PRO members, but absorbed by LLA,” he argued.

Similarly, Giorgetta noted that Macri’s camp didn’t even try to place candidates in the Buenos Aires Province legislature through mayors who refused to reach an accord with LLA. “I think it was Macri’s decision – he even left slots vacant. There were municipalities where they had strong third-way chances, but didn’t seize them,” he said.

Still, the three experts insisted it is too soon to declare PRO dead. Politics is dynamic, and surprises can always arise. In October, at least, yellow signs will still be visible.

UCR: Territory without leadership

The list-closing confirmed that the Unión Cívica Radical (UCR) remains deeply fragmented. In Milei’s first phase of government, some Radicals became staunch opponents (Facundo Manes, Martín Lousteau), others acted as allies (Rodrigo de Loredo, Alfredo Cornejo), and others outright embraced libertarianism (the so-called “Radicals with wigs”).

The anti-Milei camp failed to unite under a single label across districts. Nor did the pro-Milei side score major victories. De Loredo even publicly rejected the place offered to him, saying he wouldn’t be submissive to an accord with libertarians. Cornejo, meanwhile, had to accept that Petri – his long-time local rival – would head the list in Mendoza.

Giorgetta described the UCR as “a rudderless space,” citing the absence of the historic List 3 in Buenos Aires Province as an example of the party’s woes.

According to Butié, Radicalism today polls no more than five percent. “With Juntos por el Cambio, they accepted a supporting role, the position PRO now has in its accord with LLA. And within that hierarchy, the Radicals have slipped even lower,” he said.

Nejamkis called Radicalism a “dodecahedron,” a twelve-sided geometric shape. He argued the party’s current plight is the continuation of a process that began in 1997: “It always needs an external actor to define how it should confront Peronism.” He noted it has closed alliances over the years with FREPASO, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Mauricio Macri.

Still, the UCR governs provinces and municipalities, making it a potentially useful territorial ally. “The question is whether this fragmentation can once again be resolved by partnering with Peronism, now organised under [centrist governors’ alliance] Provincias Unidas,” Nejamkis suggested.

Provincias Unidas: political project or circumstantial alliance?

The launch of Provincias Unidas generated great expectations. Governors Ignacio Torres (Chubut), Maximiliano Pullaro (Santa Fe), Martín Llaryora (Córdoba), Claudio Vidal (Santa Cruz) and Carlos Sadir (Jujuy) presented their bloc shortly before the list-closing. Though they do not aim to compete as a unified front in October, they are optimistic about their influence in the new Congress. Their ultimate goal is to field a presidential candidate in 2027.

In the early weeks, they faced internal tensions, particularly with Juan Schiaretti. The former Córdoba governor endorsed candidacies including that of Florencio Randazzo, causing friction among the group of five governors, who are convinced their proposal should focus on newer leaders with proven executive ability. They have also encountered issues over party branding.

It is still too soon to know if this space can project itself over time or if it is just another electoral-year experiment. According to Butié, it currently polls seven to nine percent nationally, no chance of breaking the polarisation. However, he noted it could gain weight with a 2027 outlook. “Schiaretti may lose to La Libertad Avanza in Córdoba, but the 30 points he takes there will count as 30 national points. The same goes for Pullaro in Santa Fe,” he argued.

Nejamkis has long noted the existence of “a segment of voters who identify as neither-nor – neither Mileístas nor Macristas – demanding a space that represents them.” Provincias Unidas could eventually fill that gap, provided they find clear leadership, he said.

Giorgetta is less optimistic. He argued that “the group launched with force but is fading day by day, failing to close easy deals.” He cited, for instance, the fact that in Buenos Aires Province the bloc is fielding different factions – “weakening it further” – and that in Córdoba it failed to seal an alliance with leaders such as Natalia de la Sota. In his view, Santa Fe is its only real stronghold, while Chubut remains uncertain.

related news