In 2021, Tibet Action Institute (TAI) published a groundbreaking report exposing the extensive use of colonial boarding schools to indoctrinate and forcibly assimilate Tibetan children into Han Chinese culture and society. (See CDT’s two-part interview with TAI’s Lhadon Tethong on this topic.) This May, TAI issued a follow-up report that looked more closely at the conditions and treatment of children in these schools, exposing widespread abuse and the use of boarding preschools for children as young as four.

Dr. Gyal Lo at Nyen (Mountain of Deity) in Labrang, Gansu (June 2020), via Tibet Action Institute

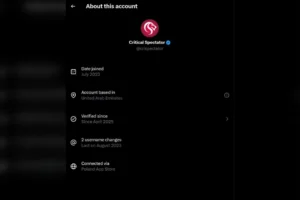

Much of the research into these schools has been conducted by Dr. Gyal Lo, a sociologist and expert in Chinese education. Born in the traditional Tibetan region Amdo (in Gansu Province under the PRC), Gyal Lo received his master’s degree from the Tibetan Language and Culture Department at Northwestern University for Nationalities in Lanzhou, China. He later taught in that department for ten years, during which time he designed and taught the first ever sociology class in Tibetan. In 2015, he got a doctorate from the University of Toronto and then returned to China to conduct academic field work before emigrating to Canada in 2020. He currently works as a Tibet specialist at TAI, and speaks and writes widely about education in Tibet. As part of our ongoing interview series about Tibet, CDT spoke to Dr. Gyal Lo on a video call. His video background was a photo of a beautiful Tibetan village nestled among verdant hills.

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

China Digital Times: So that beautiful village that’s behind you now is in Amdo, correct?

Gyal Lo: This is the place where I was born and grew up.

CDT: Can you talk a little bit about the environment you grew up in and what your education was like, especially when you were a young child?

GL: This is a semi-nomadic and agricultural place, close to the border area. We call it Tang Karnang. A [local] famous place is Labrang Monastery. It’s a rich Tibetan cultural and traditional place. I was born during the Cultural Revolution and started school almost at the end of the Cultural Revolution. That was a primary school, but not a formal school, actually. The Chinese government sent one Chinese man who only spoke Chinese language. We had, I think, around 25 kids. It was only one room. He taught us only Chinese. But at that time, our village cultural and linguistic environment was a very strong Tibetan environment. So during school, in the classroom, to do a few hours [in Chinese] did not affect us. We spoke Tibetan language and we practiced what our parents taught us. Our sense of our cultural and language identity was very strong, even under the Cultural Revolution. I went through that school system, and also got an M.A. in the Tibetan Language and Culture Department [at the Northwest University for Nationalities in Lanzhou, Gansu], and also I taught as a faculty member of that department for nearly 10 years. Then I got another M.A. and a Ph.D. at the University of Toronto. My education, I would not call it unique, but it’s a bit atypical, because I received a school education and also a very strong monastic education. On top of that, I got a Western education in Canada. So that, I think, makes me a bit unique. My academic proficiency is in three languages: English, Tibetan, and Chinese.

CDT: When you were deciding to go to university, what made you want to study Tibetan language and culture? Was it emphasized strongly in your family that that was important, or did you have some other personal interest?

GL: I had my own personal problem, my physical condition. My left foot had a problem and I couldn’t do physical work at that time. So that situated me only to succeed in studying. I asked my family, and my family also supported me very much when I said I wanted to be a professor. In 1987, I got selected into the university. That year, I felt like it was almost a different country or different cultural zone when I left my hometown. That was the first time that I left.

With my undergraduate study at Northwestern University for Nationalities Tibetan Language and Culture Department, I extended my historical view and also my cultural and linguistic foundation. That experience – receiving monastic education in the summer and winter holiday, and also receiving the [more formal] school-system education – made me a bit stronger than other kids, because I had to be able to develop my primary and secondary discourse with both a primary and a secondary language. I did that equally well, actually. So in 1994, when I finished my first M.A., the university asked me to stay there, to be an assistant faculty member. Then I started teaching there.

During my teaching, I found myself dissatisfied with the course that they [assigned] me. I thought that it might not be good for students, either. So I told the chair of the department I wanted to design a new course. And they said, “What kind of a course do you want to teach?” I said I wanted to teach sociology. That was the first time [that anyone taught sociology in Tibetan]. It was a creative course I did. At the beginning, I read the translated version of the sociology book in Chinese; the original book was published in America. The author’s name, I think, was Cohen. I read his [book] and then I taught the course in Tibetan language, the first ever. I think that’s what attracted a lot of students – applying the effective framework to identify social and cultural issues. And at the same time, in our department, we had students from [all over Tibet]: U-Tsang, Kham, Amdo. But the common thing is that most students, when they submitted assignments to me, there were so many structural problems [in their writing]. And I asked them, “What’s wrong with you guys? When you are speaking, you speak perfectly. But when you write something, it’s very strange.” And then they say, “Teacher, that’s the way the school taught us.” So we started rethinking, “What’s wrong with our education?” At that time I had one friend who was the first Tibetan to get a Ph.D. in Education. He and I were very close, and we discussed Tibetan education more and more. We started to analyze the curriculum, the textbooks, etc. We started to realize the boarding schools were a huge problem. Until 1995, we didn’t realize that there was a problem with the colonial boarding schools.

CDT: At that point in 1995, how common were the boarding schools?

GL: I think they already [had been running for] 15 years. Some of our students already came from those boarding schools.

CDT: And at that point, what kinds of students were going to the boarding schools? Was it just in the rural areas?

GL: At that time, no matter rural or urban, all seemed to be in the boarding schools. A few students whose families were very close to school didn’t really need to board. But the other students, the majority of students, were boarding.

In 1982-84, they started to build village schools. But that’s only until grade five. After grade five, you have to go to the township school, then in the township school, you have to board. Even at that time, the older generation thought our people needed to receive education, urging the people and the parents to send their kids to school, without understanding the problems of the boarding schools. From 1995, we realized there was a huge problem, because China, at that time, had already extremely centralized their curriculum. They only allowed us to translate their textbooks into the Tibetan language. The translations were very poor quality. So that’s why the students had poor sentence structure.

CDT: This new report that TAI put out is the second one on this topic, but this report has new evidence that shows the impact these schools are having on children. It sounds like you were starting to already see that impact in 1995. What do you find most concerning from what you and TAI found while researching this new report?

GL: This new report found not only the curriculum and psychological issues that students in the boarding schools are facing, but also the physical difficulties. The videos and evidence that we received are from many different places. So that means that kind of physical violence or abuse is happening in many places, not only one single place. The second issue in this report is the Chinese government taking the young monks from the monasteries to put them into boarding schools. It’s very hard for the young monks to adapt to the school style. They try to escape from the boarding school, and then the local officials and the school principals want to keep them in the school. That’s why those kids get frustrated and don’t want to stay in the schools. They run away and then they feel like there is no way for them to get back to the monastery. [Some] tried to commit suicide. That kind of thing is happening not only in one place, but in several places.

CDT: You mentioned that you yourself went to the monastic schools on the weekends and holidays. Can you talk about the traditional role of those monastic schools? What is being lost with the loss of these monastery schools in Tibet?

GL: When I was a teenager in monastery study, the content was purely our own culture. The language and the content were highly consistent. We had no difficulty in our way of thinking, by using the language and learning the content. When our children went into the boarding schools, there was an inconsistency between the family language and the school language. The school teaches a totally different language and different content, which are irrelevant to their home culture and home language. That creates a psychological difficulty, and difficulty with their way of thinking and the effectiveness of the learning. So that [reduces] the quality of the learning and their thinking ability. Those are the key issues. [The Chinese are] trying to produce this Tibetan generation as cheap labor. One day, they graduate from school, and come back home, but they fit neither home society nor Chinese society. For those generations now, the only option for survival is to become cheap labor in Chinese cities.

CDT: And do you think that that’s the intention of the Chinese government with these schools?

GL: Of course, they intentionally design this.

CDT: Now you’ve discovered the existence of these boarding preschools. Which children are most likely to end up in those preschools and what are the conditions like in those schools?

GL: The preschool programs were [launched] in September 2016. At the beginning, their facilities were very poor; they had no preparation. But I think since 2019, their school facilities have improved very much. But my key concern is not about the facilities. My key concern is they are purely indoctrinating our kids at such a young age – four, five, six. They’re keeping them in boarding schools, and then they’re teaching them only Chinese language and only Chinese culture. They are completely cut off from their parents, their family, community, and culture. After three months, the children in the boarding preschools become strangers at home. After seven years, in 2023, I did a research inquiry with them. Those kids had started confidently standing up to criticize their family members who are not able to speak Mandarin. This is not too small a number. It’s [happening] across Tibet. This is a serious shift. After three months, you became a guest or stranger at home, your own home. After seven years, you start to stand on the other side, criticizing your family members. So this is how China’s colonial boarding preschools affect [the children].

China is investing not only financially, but also intellectually and pedagogically. They created pedagogical techniques, pouring the Chinese language and culture into the Tibetan kids. For example, young teachers without any experience came to do experimental teaching. They bring Chinese cultural objects everyday and put them on the table. Then they ask the kids to close their eyes and imagine [the objects]. Then when they open their eyes, they ask them to draw what they have imagined. They start asking them to use Chinese to explain what they have drawn. That’s kind of a forceful push. The kids are scared every day, every moment, in the school. They have almost no privacy [or] freedom. They’re pushing them. So the kids quickly forget their mother tongue, and get Chinese as a fundamental language. That’s why after three months, they became strangers. They can’t engage in the family conversation. More seriously, I observed kids sitting there and you see them, their faces, they seem really uncomfortable, sharing the same identity with a family member. They have that kind of sense already. That’s not only one small case, that’s because of the preschool education policy. They implemented it across Tibet.

Based on my experience, what I saw and my general knowledge about the Tibetan population, it’s way more than a million kids [in boarding schools].

CDT: Have you had a chance to speak to students who’ve already gone through the whole education system, when they are young adults or adults, and to talk to them about their own sense of identity as a Tibetan, and if they were able to retain that, or what their feelings are?

GL: When I saw the problem, I spent four summers doing fieldwork. I had a chance to talk to the teachers, kids who were in the boarding preschools, and young mothers of the children. Also, those unemployed graduates who previously experienced boarding school. They have a reversible sense of identity. They’re not able to keep their sense of [Tibetan] identity very strong. But those five-year-old kids I talked to say, “I don’t know the consequence of being in this school. But I start missing my mom and grandma. I can’t take care of myself. After class, there’s a process, you change clothes and then you have dinner and then you go to bed. All those processes, I can’t do them. I don’t know how to take care of myself.” Age five! Of course, I’m not denying 100% that the schools have no good care, but the majority of the schools do not have enough caregivers for them.

CDT: Have you seen some examples of ways that Tibetan families are managing to preserve their children’s ties to their language and culture? Are they doing things in the house to try to counteract the impact of the schools when the children are home, that have been effective?

GL: From 2023, they are collectively doing these activities more on the weekends when their children come home. Some of the young parents cannot do this, but their grandparents moved close to the school. They want to see their kids every day, even if they can’t get into the school. They rent a room, and sometimes they stay in the car, beside the school. Young mothers are already demonstrating about those schools. Such young kids are being taken away from them. They organized a group of women who walked to Lhasa, a thousand miles away, as a demonstration. They said, “We can’t live like this without our kids. We miss them too; it’s not only that the kids miss us.”

CDT: What has the response been to those kinds of demonstrations?

GL: Those women walking to Lhasa, it took three months. Every day, each evening, when they got to a village, they sought shelter. At the beginning, the villagers provided them with shelter. When the Chinese local governments saw that, they punished the family who provided this hotel for them. So those are the very practical and very serious problems between women and local governments. Because such young kids have been taken away into the boarding schools, young mothers are starting to face mental problems. And it’s not just one woman: it’s many. In order to release their mental stress, they just try to walk to Lhasa, as a demonstration. This is affecting the community, entire villages. Many women, young mothers who organized, say, “We can’t take our children back home, what can we do?” Then they start to organize a collective cultural activity when their kids come home from boarding school on the weekend. They dress up and do ritual activities.

CDT: Since you’ve been through the Tibetan education system and you’ve also studied it, what would the ideal education for a Tibetan child look like, so that they could be prepared to have economic and personal success in today’s Tibet and the bigger world, but also preserve their own culture and identity and language?

GL: I designed a curriculum already. I think children need a culturally relevant education. The textbooks should be based on Tibetan cultural knowledge or practical knowledge, and also the traditional knowledge, too.That will prevent alienation and also the identity crisis. This February, I visited the Tibetan community in India. I saw the Tibetan community using Tibetan language and practicing their culture. They would be able to manage it and develop their community, if they had freedom inside Tibet. China always says Tibetan language is backward, Tibetan culture is backward, it’s only a religious-based culture system. No! We’ve been using our language, carrying out our civilization for more than 4,700 years. Our language is a capable language in a modern context. Learning Tibetan doesn’t mean rejecting modernization. We do need modernization. We accept modernization, but we need modernization by using our own language. If we have a strong mother-tongue foundation, then we’re happy to learn a second or third language. No problem.

So my curriculum, my education would be like this: it would carry out the strong cultural capacity and the language capacity and proficiency, and also use new knowledge to develop society and support [Tibetans’] economic survival in society. Tibetans today, even myself, I have three languages. It doesn’t mean that to have Chinese or English is a problem – no, because I have a strong mother-tongue foundation. The Tibetan education is a culturally relevant education. That must be there. But now what China is providing is not even a formal education. It’s assimilation. The CCP [is enforcing] CCP loyalty, and also teaching Xi Jinping Thought in the curriculum. So there’s no room for formal knowledge to be learned. That’s why I’m calling this “not a formal education.” It’s indoctrination.

CDT: How optimistic are you about the ability of the Tibetan language and culture to persist within Tibet? Or do you think the culture and language and traditions will continue most strongly outside Tibet?

GL: Based on the population research, and also the 2020 census, Tibetans in their Tibetan homeland are still the majority. My age, the over-50 generation, is still very strong in their language and culture. If any possibility or opportunity comes, it will flourish again, I think.

CDT: Is there anything else you would like our CDT readers to know – either about these schools or about this new report or about the situation in Tibet more generally – that I haven’t asked?

GL: What’s the policymakers’ approach on this? Since 2018, Xi Jinping has been particularly against cultural and racial diversity in China. Under that philosophy or framework, they have carried out the policy to promote their “one language, one culture, and one country.” This leadership, this CCP system, we need it to open up. Otherwise, those harmful policies are not only put on Tibetans, but also Uyghur people, Mongolians, and other ethnic minorities too – the Guangxi Zhuang minority, and there are many minorities in Yunnan, too. They will make other populations suffer in the future. So it’s time to increase the pressure to force them to change what they’re doing now.

CDT: How would you like to see the international community apply this pressure to help the situation?

GL: According to my knowledge of China, Chinese culture, and the Chinese people, they listen to power and strength. So they’re scared of the U.S. and they’re scared of the international community. If we all firmly stand in solidarity together, then we have powerful pressure on them and they will listen. But the problem now is that China’s repeated lies have become truth in many international organizations and institutions. China thinks that they can break the international community’s solidarity apart one by one. The international community in this sense needs to increase the quality of their solidarity and then firmly stand with their principles of democracy and human rights, all those common values. It’s time to bring China to democracy, or the international community can take democracy and human rights to China.

Additional resources on Tibet’s colonial boarding schools:

Bonus resource: Resource Guide to Decolonizing Reporting on Tibet (July 2025) – “Tibet Action Institute presents this Resource Guide for Decolonizing Reporting on Tibet as a tool for journalists, editors, researchers, policymakers, students, and others seeking to report on Tibet with accuracy, integrity, and respect for Tibetan voices.”

In such a repressive environment, how do Tibetans in Tibet hold onto their cultural identity? How does the world find out what is happening there? How do exiles stay connected with their families and homeland? Where can we find hope for the future of Tibet and Tibetans? CDT has launched this interview series as a way to explore these questions and to learn more about current conditions in Tibet, efforts to preserve Tibet’s religious and cultural heritage, and the important work being done every day by activists, writers, researchers, and others to help and support Tibetans inside and outside the region. Read previous interviews in the series.