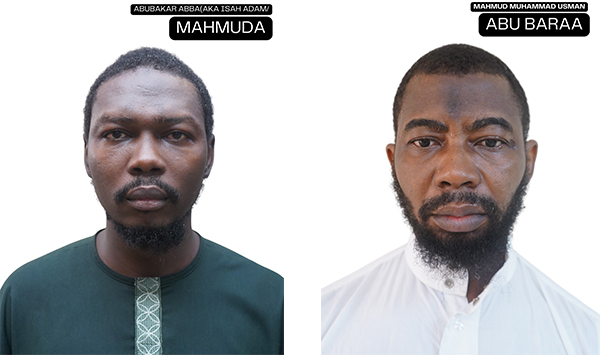

On 16 August, the Nigerian government announced it had captured two leaders of Ansaru, an al-Qaeda franchise in Nigeria—but little is known about these bigwigs. In this report, we profile them based on interviews with local sources and secondary data collated by jihadi experts.

The two men: Mahmud Usman, also known as Abu Bara’a, and Mahmud al-Nigeri, notoriously known as Mallam Mamuda, were arrested after a months-long, intelligence-driven operation between May and July, according to National Security Adviser (NSA) Nuhu Ribadu.

Mr Ribadu, who described Abu Bara’a as the “Emir of Ansaru,” said he was the overall coordinator of the group’s sleeper cells across Nigeria and mastermind of several kidnappings and terrorist financing operations.

He explained that Abu Bara’a was deputised by al-Nigeria (Mallam Mamuda) , who headed the notorious “Mahmudawa” faction of Ansaru based in and around Kainji National Park and trained in Libya under foreign jihadist instructors from Egypt, Tunisia and Algeria, “specialising in weapons handling and IED fabrication.”

In this report, PREMIUM TIMES digs deep into the background of the terrorists.

From prison to power: The rise and fall of Abu Bara’a

An ex-inmate and longtime jihadist, that is what experts said about the captured overall leader of Ansaru.

Before the 2012 schism that led to the formation of Ansaru, Mr Abu Bara’a was one of the remaining early Boko Haram leaders who, according to security analyst Daniel Simón and researcher Vincent Foucher, became a qaid [mid-level commander] in the amniyya, the internal security section that Boko Haram founder Mohammed Yusuf created within his movement between 2005 and 2007.

The terror leader was, sometime around 2011, arrested by the military before a negotiation between the Nigerian government and Boko Haram. Taiwo Adebayo, a Lake Chad Basin researcher with the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), told PREMIUM TIMES that Mr Abu Bara’a was to represent Boko Haram in that negotiation.

He was subsequently imprisoned in Koton Karfe, a 50-bed prison facility about 25 kilometres from Lokoja, the capital of Kogi State.

But he was set free in February 2012 when his brothers-in-arms stormed the prison facility with explosives. The prison break resulted in the escape of more than 100 inmates, including Mr Abu Bara’a and six other Boko Haram members, Mr Adebayo said.

The ISS researcher said it was after the prison break that an internal fracas erupted, splitting Boko Haram for the first time.

“The schism was caused mainly by two things: the disagreement over how the money sent to Boko Haram by al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden should be utilised,” Mr Adebayo said. “The second reason was their dissatisfaction with Shekau’s ultra-takfirism, which justifies the killing of civilians, including Muslims who do not subscribe to jihadi ideology.”

Mr Abu Bara’a became one of the founding members of Ansaru. He rose to the group’s leadership position after the well-known Ansaru leader Khaled al-Barnawi was arrested in 2016.

Mr Abu Bara’a’s ethnicity is Ebira, from Okene, Kogi State. The Maiduguri-raised terror leader, nicknamed Abbas before becoming a terrorist, had an ambition to become a military officer, but was denied entry, according to Messers Simón and Foucher.

Mr Abu Bara’a finished his secondary school studies at El Kanemi College of Islamic Theology, a private institution where his father, a respected mainstream Islamic scholar, served as a department head.

“After completing his secondary studies, Abbas, who had a strong vocation for military life, attempted to enter the National Defence Academy,” Messers Simón and Foucher wrote in an article spotlighting Mr Abu Bara’a. “Lacking the necessary connections and patrons, he failed to join the defence establishment and, around 2001 at the age of 18 or 19, found himself disillusioned and at a crossroads. While his father encouraged him to pursue further studies for a regular university degree, Abbas remained uncertain about this path.”

Mr Abu Bara’a’s foray into jihadism dates to his post-secondary education stage when a group of students led by a Saudi Arabian deportee, Mohammed Ali, “began to challenge the Islamic establishment in Maiduguri.”

It also coincided with the time that Mr Ali (killed in a battle in 2003) and some of his Salafi-Jihadi followers travelled to Niger, Algeria and Mali for training with the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC).

Although the group didn’t adopt any name, the media referred to them as “Nigerian Taliban.” However, the authors couldn’t tell whether Mr Abu Bara’a was part of those movements, but they opined that: “By generation, class, and education, he (Abu Bara’a) resembled the Nigerian Taliban or early GSPC associates more than Yusufiyya (Boko Haram founder) followers.”

Mr Abu Bara’a, according to security sources cited by these authors, was trained by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) between 2013 and 2015.

Around 2017, he held the position of Amir (leader) and “authored or reviewed” a lengthy article for al-Qaeda propaganda outlet, Risala, under a pseudonym, Sheikh Abu Usamatul Ansary.

The wealthy warlord

Mr Mamuda’s background is not fully known to researchers. Although some sources said he is from Kano State, there is no substantial evidence to prove that.

Until his recent capture, Mr Mamuda, the feared leader of an Ansaru faction operating from the Kainji forest, built a reputation that blended deception, coercion and ruthless profiteering.

Locals told PREMIUM TIMES that Mr Mamuda first presented himself as a protector, casting his presence as a form of community defence. He allowed villagers and artisans into the otherwise restricted forest reserve, granting them access to hunt, fish, farm and log. But this access came at a cost.

Those who sought to earn a livelihood inside the reserve were compelled to pay him heavy levies. A logger who encountered Mr Mamuda last year said logging groups paid as much as N1.5 million every week to his fighters.

“His younger brother, Aiman, coordinated the extortion,” said the logger whose identity has been concealed for security reasons. “If you disobey them, either not renewing your fee or going beyond a marked area, they kidnap you and collect a ransom ranging between N5 and N10 million.”

While he could not estimate revenues from other activities, he admitted that Mamuda profited massively from farming, hunting and other illegal exploitation of forest resources.

Beyond this structured extortion, Mamuda’s gang orchestrated a series of high-profile kidnappings that spanned Nigeria and parts of the neighbouring Benin. Among the incidents were the abduction of seven surveyors working on the Lagos-Badagry-Sokoto highway, whose release was negotiated through the emir of Yashikira after ransom payment.

“They kidnapped the surveyors the very first day they came into the town,” a resident of Karonji told PREMIUM TIMES. “They seized their equipment and matched them into the forest.”

In another case around Nanu village, the group abducted car dealers returning from Cotonou, Benin Republic, collecting about N12 million.

Also, the terrorists recently kidnapped one Isah Abubakar, a lawyer and businessman. They collected N20 million for his release. Mr Isah’s brother was fatally shot during an escape attempt. He died a few days later.

The group also staged violent raids on Babana, Luma in Niger State. It also raided Karonji and Kemanji in Kwara.

In Dagazi, a border village in Benin, they kidnapped worshippers from a church, demanding 10,000 CFA, a resident of Gbesasi, another border village near the scene of the incident, said.

In audio messages to residents, Mr Mamuda branded vigilantes as his sworn enemies and vowed revenge on communities that collaborated with the military.

READ ALSO: Nigeria captures top globally-wanted Ansaru terrorists behind several atrocities

Ansaru

Ansaru, formally known as Jama’atu Ansarul Muslimina fi-Biladis Sudan, broke away from Boko Haram in 2012 as a more humane faction. But it quickly became violent, targeting civilians, security forces and public infrastructure.

The group, which pledged allegiance to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), took part in high-profile crimes including the 2022 Kuje prison break in Abuja, the 2013 abduction of French engineer Francis Collomp in Katsina, the 2019 kidnapping of the Magajin Garin Daura, Musa Uba, the abduction of the Emir of Wawa and the deadly attacks on a Niger uranium facility and other cross-border operations.

The arrest of Messrs Abu Bara’a and Mamuda, experts believe, will unsettle the Ansaru group. It could lead to infighting that may further decimate it and possibly split it into factions.