WASHINGTON — In his first term, Donald Trump’s favorite president, other than himself, was Andrew Jackson, the hatchet-faced, self-made populist who relished turning Washington upside down.

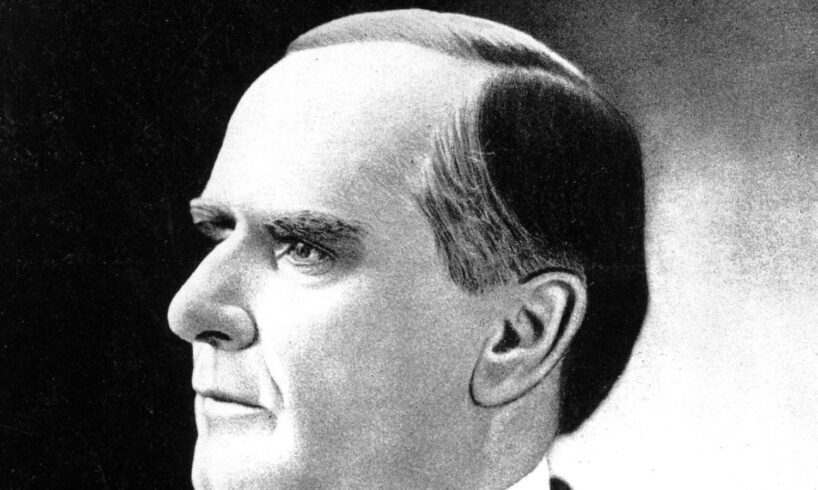

Now he’s partial to the barrel-chested, unfailingly polite William McKinley, a champion of American expansionism as well as of tariffs, Trump’s favorite second-term policy.

Trump’s shift, rather than merely swapping one infatuation for another, demonstrates how his mindset and priorities have evolved.

The Republican president’s admiration for McKinley fits with his current politics, which are different from when Trump first took office in 2017. A key political target for Trump back then was the elites, which his administration predicted might crumble in the face of a Jackson-like working class uprising.

In his second inaugural address, Trump lauded McKinley as a “natural businessman” who “made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent.”

Trump used a Day 1 order to restore the name of North America’s tallest peak to Mount McKinley and he has repeatedly named-checked the 25th president more recently, while his weighty tariffs have left the world bracing for the kind of trade war not seen since the days of the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890.

Jackson has hardly warranted a mention.

“In the first term, well, McKinley was a fat cat,” said H.W. Brands, a history professor at the University of Texas and author of “Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times.” “So, if you’re going to be a populist, you’re not going to be a McKinley.”

But Jackson, Brands noted, hated tariffs. “So, if tariffs are your thing, Andrew Jackson’s not your guy anymore. You have to look around to find somebody whose name is connected to a tariff.”

The White House says the shift isn’t a departure from Trump’s first-term goals, but simply his leaning harder into new tools — in this case, tariffs — to achieve them.

“President Trump has never wavered from his commitment to putting working-class Americans above special interests, and his channeling of President McKinley’s tariffs agenda is indicative of how he is using every lever of executive power to deliver for the American people,” said spokesman Kush Desai.

Still, many of Trump’s current top advisers are veterans of the financial sector eager to help the president bend the economic system to his will, rather than reshaping it from the bottom up.

That’s meant Trump focusing political ire on foreign countries and “globalists” who embraced international free trade. He wants to impose a new economic order that puts U.S. interests first, and has settled on steep import taxes to get America’s trading partners to negotiate more favorable deals — as the way to most efficiently do that.

The president’s Jacksonian impulses aren’t all dormant. He imposed some first-term tariffs and now is shaking up Washington with his efforts to slash the federal workforce and stock the bureaucracy with loyalists. He’s also prioritized antagonizing “elites” at Ivy League universities and top law firms.

In his rhetoric, Trump also has mythologized the power of tariffs, despite history telling a different story. Tariffs in the McKinley era, which loosely tracked the Gilded Age, led to more income for the federal government, but also a highly stratified society of haves and have-nots.

But just as Jackson allowed first-term Trump — a magnate who had little in common with many working-class voters he wooed — to take up the mantle of modern populist, McKinley gives Trump an intellectual justification and historical precedent for his love of tariffs.

“It’s a vibe shift for sure,” said Eric Rauchway, a history professor at the University of California, Davis, and author of “Murdering McKinley: The Making of Theodore Roosevelt’s America.”

It’s also an example of Trump taking policy actions to move the country in a certain direction — or simply declaring what he wants to be true — then working backward to come up with an argument on why his instincts were correct all along.

“Trump’s relationship to history, and so many other things, is entirely transactional,” said Daniel Feller, a professor emeritus at the University of Tennessee and former longtime editor of “The Papers of Andrew Jackson.”

Jackson was the founder of the Democratic Party, though many on the left now reject him for being a slaveholder who imposed the “Trail of Tears” on Native Americans. Orphaned at 14, Jackson taught himself the law and eventually became wealthy.

Yet he created a political persona around advocating for everyday Americans. Trump, during his first term, referred to Jackson as the “People’s President.”

McKinley, who was assassinated in 1901, six months into his second term, was born in Niles, Ohio, outside Youngstown. He fought with the Union army and preferred throughout his political career to be called “Major,” the Civil War honorary title he earned.

As a congressman, McKinley was known as the “Napoleon of Protection” for promoting the 1890 Tariff Act, which sharply raised import taxes on thousands of goods in an effort to protect American producers when there was no federal income tax. It ultimately increased prices domestically, hurt U.S. exporters and helped spark the Panic of 1893, the worst economic downturn until the Great Depression.

McKinley also represents a burst of American colonial expansion. He annexed Hawaii and oversaw the U.S. taking control of the Philippines. His administration also acquired new territories in Guam and Puerto Rico, established a military government in Cuba and sent troops to China.

Today, Trump has talked about the U.S. invading Panama and Greenland, making Canada the 51st state and turning the Gaza Strip into the “Riviera” of the Middle East.

In July, in comments about which of his predecessors got prime White House wall space, Trump mentioned “the Great Andrew Jackson.” But he praised McKinley, saying that the U.S. “was the wealthiest” from 1870 to 1913, when it was “an all-tariff country.”

“We had a couple of presidents that were very, very strong,” Trump told his Cabinet then. “McKinley, I guess, more than anybody.”

On social media last week, a Trump aide posted a picture of a new, gold-framed portrait in the West Wing featuring Trump alongside McKinley, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, and Henry Clay, over the title “The Tariff Men.” Lincoln used high tariffs for Civil War funding, Jefferson was a free-trade advocate but supported some tariffs to bolster domestic industries. Clay, as House speaker, helped pass a major tariff act in 1824.

What Trump doesn’t mention is that McKinley’s tariffs helped cost the GOP its House majority in 1890, with McKinley himself among those defeated. He returned to Ohio, was elected governor and, despite going bankrupt over a bad investment in a tin plate company, won the White House in 1896.

After that, though, Rauchway said, McKinley actually didn’t push tariffs as much following his experience with them in Congress. Just before he was killed, McKinley also talked up the need for international trade.

That didn’t stop Trump, in announcing sweeping tariffs around the globe in April, from saying the U.S. had been “looted, pillaged, raped and plundered by nations near and far.”

His championing of tariffs isn’t totally new. In his first term, Trump ordered some higher import taxes on solar panels, washing machines and steel and aluminum imports. He also occasionally praised McKinley, then, as when he said in a 2019 speech that the 25th president “was very strong on protecting our assets, protecting our country.”

But Trump conceded in that same speech, “I’m totally off script.”

That’s no longer the case. Trump continually promotes McKinley’s place in history.

“McKinley was a great president,” Trump said during last month’s Cabinet meeting. “Who never got credit.”