Off the icy continent’s coast lives a pale pink octopus that hunts bristle worms and shrimp-like crustaceans across the sea floor.

“They occur all the way around Antarctica, so they’re a circumpolar species,” Strugnell explains over the phone from an oyster conference in Tahiti.

“They occur from shallow depths down to a little over a kilometre.”

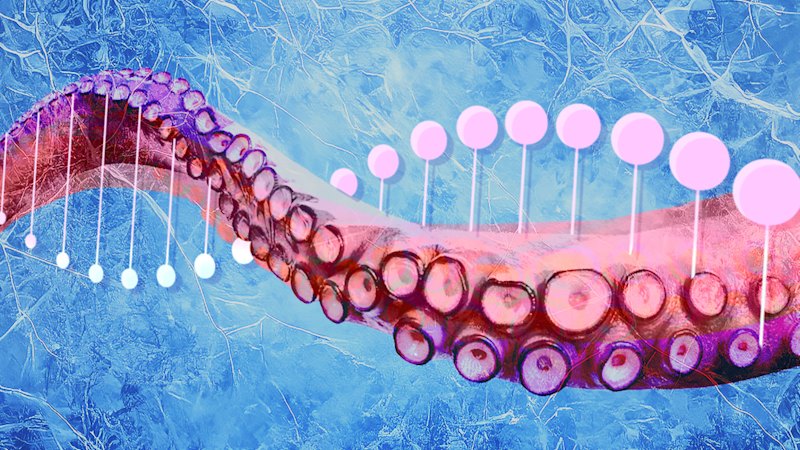

The pink octopuses grow to about 15 centimetres and live all around Antarctica.Credit: Pete Harmsen

This species, called the Turquet’s octopus, doesn’t have a larval stage, unlike many other marine species that drift in the water column for long distances. They also don’t travel very far as adults.

Distinct populations live in the Weddell, Amundsen and Ross seas, which today are all separated by the ice sheet.

The only way these populations could mix is if the rocky channels underneath the ice sheet opened up, allowing cross-continental cephalopod lovers to meet up and interbreed.

Researchers traced through the genetics of the Turquet’s octopus to find when three now-separated populations last interbred. Credit: Strugnell et al, Science

“The only way that that could have been the case is if there wasn’t any ice sheet there at all,” Strugnell says.

Find the last time these octopus populations interbred, and you’ve identified when the ice sheet last collapsed.

23andMe for tentacles

This type of genomic/geological detective work was made possible by leaps forward in our ability to sequence and analyse DNA.

Professor Jan Strugnell investigates molecular evolution in deep sea Antarctic species.Credit:

Most of these tools were improved for human use, such as the saliva swabs used by the now-collapsed company 23andMe to reveal the ancestral history of their customers.

“Your DNA, my DNA, contains a record of all of our ancestors. It’s a time capsule. And you can use the DNA from an octopus or a human and understand a lot about their past population size and connectivity,” Strugnell says.

“It’s along these lines that we could understand that octopus populations on either side of Antarctica used to be connected, where today an ice sheet exists.”

Strugnell and her colleagues analysed a range of tiny tissue samples from the octopuses, some from 40-year-old specimens kept pickled in museums.

West Antarctica has enough ice to raise global sea levels by more than three metres if it melts.Credit: Ian Joughin

This genomic data answered their glaciological question. There, in the DNA, lay signals that showed the octopuses from the three different seas last exchanged genetic material about 125,000 years ago.

The team had their answer. It was a shocking one.

What the octopuses warned us

The time the ice sheet collapsed, according to the octopus DNA, is called the Last Interglacial period. Global temperatures and carbon dioxide levels were very similar to what they are right now.

The scientists concluded their octopuses had revealed the first empirical evidence that the colossal, world-shaping ice sheet could begin to collapse even if we fulfil the Paris Agreement of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. Temperatures during the last collapse were only between 0.5 and 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

“It’s great to be able to address a question that people have been trying to answer since the 1970s. But, you know, it was also really very depressing,” Strugnell says.

“The implication of the work is that we might be subject to sea level rise of three metres or more. This is very hard for us to imagine. There are many, many millions of people that live in very low-lying coastal areas, including in Australia.”

In the short term, the finding allows climate scientists to sharpen up their modelling tools for what might unfold in Antarctica, now that we have a better idea of its relatively recent (geologically speaking) past.

Loading

Strugnell says other teams are now using the DNA technique to estimate past population sizes of Antarctic creatures on the sea floor. This gives us crucial data about historical advances and retreats of ice sheets all around the continent.

“Antarctica feels like such a long way away. And perhaps even in people’s minds, it’s stable,” says Strugnell, who is part of an Australian Research Council initiative called Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future.

“But what happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay in Antarctica.”

The power – and politics – of collaboration

Global collaboration between biology buffs, climate wonks, zoology nerds and glaciology gurus broke the scientific deadlock of solving the ice sheet’s past.

But often, interdisciplinary work isn’t as simple as an astronomer and a volcanologist swapping notes.

Strugnell says it can be more difficult to get this kind of research published because scientific reviewers baulk at papers with content outside their study area – and that’s basically guaranteed with a paper that spans glaciology and octopus genetics.

Part of the research team, including Nick Golledge, Nerida Wilson, Sally Lau, Tim Naish and Jan Strugnell.Credit: Sally Lau

It takes a strong editor to bring people together and match the right reviewers with the right parts of the paper to help evaluate its scientific rigour as a whole.

“Scientific fields have quite a lot of jargon. We’ve got different ways of communicating about what we do, often working on different temporal or spatial scales,” Strugnell says.

“It takes a really long time to make sure you’re all even starting on the same page.”

Make the effort to work together, however, and you might find the future of our planet written in the genes of an octopus.

Other winners of this year’s Eureka Awards

Environmental Research: The Living Seawalls Project (Macquarie University; UNSW; and Sydney Institute of Marine Science)Forensic Science: Towards a Smart PCR Process (Flinders University and Forensic Science SA)Interdisciplinary Scientific Research: Octopus and Ice Sheet Team (James Cook University; CSIRO; Antarctic Research Centre)Scientific Research: PINK1 Parkinson’s Disease Research Team (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute)Sustainability Research: Professor Anita Ho-Baillie (The University of Sydney)Emerging Leader in Science: Dr Aaron Eger (UNSW and Kelp Forest Alliance)Leadership in Science: Distinguished Professor Ian Paulsen (ARC Centre of Excellence in Synthetic Biology, Macquarie University)Innovation in Citizen Science: Passport2Recovery (Flinders University)Promoting Understanding of Science: Dr Vanessa Pirotta (Macquarie University)Societal Impact in Science: Professor Thomas Maschmeyer (The University of Sydney)Read the full list of winners.

Source