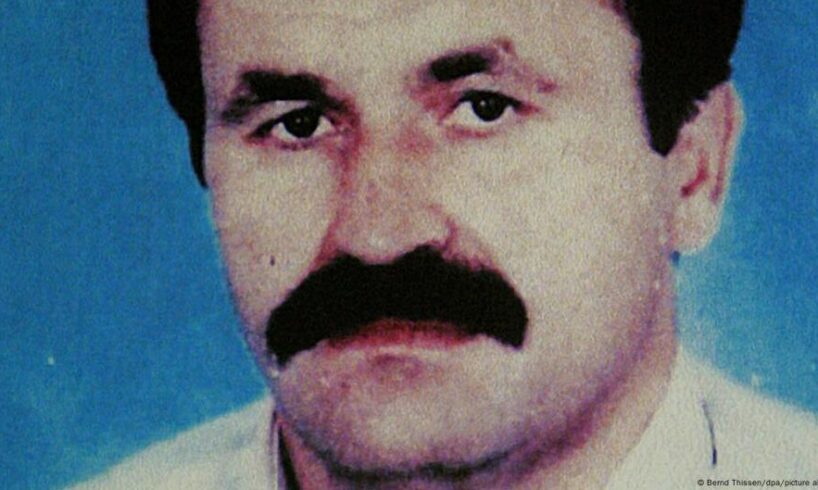

Nuremberg, September 9, 2000: The Turkish-born florist Enver Simsek was waiting for customers at his roadside stall when his murderers ambushed him in the early afternoon.

They shot the 38-year-old father eight times, with five bullets htiting him in the head. He died two days later from his severe injuries.

Simsek did not regain consciousness before dying and was thus not able to give information about what had happened or who had attacked him. It was not until 11 years later that Simsek’s wife and her two children found out who was responsible for killing their husband and father: a terror group, which named itself National Socialist Underground (NSU) and was until then unknown to the public. Its motives: hate and racism.

The NSU was uncovered on November 4, 2011. On this day, after a failed bank robbery in Eisenach, Thuringia, two men very likely took their own lives in a campervan, under circumstances which have never been fully explained. Their names were Uwe Böhnhardt and Uwe Mundlos. Their accomplice Beate Zschäpe, who was eventually sentenced to life imprisonment with preventative detention in 2018, exposed the trio.

Police seemed to be oblivious

Zschäpe, who was 36 at the time, sent several copies of a confession video to different organizations, including media outlets. In the macabre compilation, the NSU boasted of murdering Enver Simsek and others.

Beetween 2000 and 2007, the trio had traveled across Germany, shooting eight more men with Turkish or Greek origins. The 10th and final victim was the female police officer Michele Kiesewetter.

Germany was shocked. How could a right-wing extremist terror group execute people with non-German origins according to the same pattern for seven years without the police and the Office for the Protection of the Constitution noticing?

Enver Simsek’s daughter, Semiya, who was a teenager when he was murdered, still asks herself this question ― and many others. Though she was born in Germany, she now lives in Turkey.

Police suspected the family of the murder victim

In February 2012, three months after Zschäpe unmasked the NSU, Semiya Simsek gave a moving speech at a combined memorial service for all of the NSU’s victims, which was held in Berlin. She spoke of her grief and despair ― and of humiliation. Because after her father’s death, investigators focused on his familyin their search for the perpetrators.

“For 11 years, we were not allowed to simply be victims,” she complained, reflecting on that time of uncertainty.

She bore the burden of thinking that somebody from her family could be responsible for her father’s death. And there was also some suspicion that he had been involved in criminal activities or drug dealing.

Chronology of NSU murder spree

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Angela Merkel: ‘I ask your forgiveness’

“Could you imagine how my mother felt to suddenly be a focus of the investigation?” Semiya Simsek asked. During the memorial service, then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel labeled the yearslong suspicions as “nightmarish” and, addressing the bereaved relatives, added: “For that, I ask your forgiveness.”

In 2013 the NSU trial began at the Higher Regional Court in the southern German city of Munich. It finished in 2018.

“We were all there on the first day,” said Semiya Simsek in a 2024 video, which features on the website “Orte des Erinnerns Nürnberg” (Place of Remembrance Nuremberg). She described how uncomfortable it felt to be in the courtroom: “There were also a lot of Nazi visitors there.”

No government help

The website, which went online in March 2025, is a civil society partnership that includes the city’s Human Rights Office. In the video, Simsek recounts fond memories of her father from her childhood. She calls the years between his death and the NSU being revealed “the most terrible, the dark time.” During this period, she received no support from the government or other authorities.

“After the revelation, many people wanted to support us. But at 25 I didn’t need that kind of support anymore. I wanted it when I was 14,” she said.

When it was finally clear who had murdered her father, the distrust toward her and her family turned to sympathy.

Demands for more than sympathy

People regretted not believing her, said Semiya Simsek, but their words came too late and evensounded like a mockery to her 11 years after her father’s death.

“I have already tried to somehow come to terms with this myself,” she said.

A quarter-century after the first NSU murder, she and Gamze Kubasik — whose father, Mehmet Kubasik, was shot by the NSU on April 4, 2006, in Dortmund — have written a book about their shared fate. Titled “Unser Schmerz ist unsere Kraft,” which translates as “Our pain is our strength,” it shares their family stories, the failings of the investigation in the NSU case and the battle for remembrance.

“I cannot make peace,” said Semiya Simsek, referring to the many questions that remained unanswered in the NSU trial and parliamentary investigative committees. “That is also why I continue to go public and say: ‘We cannot be finished with this.’ I am still plagued by questions: Why my father of all people? How were these victims chosen? Why are the accomplices not being investigated?”

Semiya Simsek, Gamze Kubasik and many other bereaved family members continue to hope for answers. The same is true for the survivors of other assassination attempts by the NSU. Especially the 22 people who were injured, some of them severely, in a nail bomb attack that targeted Cologne’s Keupstrasse, known as being a Turkish business hub, in the western German city on June 9, 2004.

This article was originally written in German.

While you’re here: Every Tuesday, DW editors round up what is happening in German politics and society. You can sign up here for the weekly email newsletter, Berlin Briefing.