The children were sleeping when death came from the air. A military warplane dropped two 500lb (230kg) bombs on their boarding school, witnesses said. Imagine, if you can, the carnage and the horror. At least 18 died. Others suffered life-changing injuries. The ruling regime claims to be fighting terrorists. Yet more often than not, it is defenceless, blameless civilians who are killed, maimed and displaced. No, this isn’t Gaza. It isn’t Ukraine. It’s Myanmar, where appalling atrocities, including crimes against humanity, often go unreported and unpunished. That doesn’t render them any less heinous or less deserving of universal condemnation.

Myanmar, formerly British-run colonial Burma, where civil war has raged since an army coup overthrew the elected government in 2021, is a microcosm of today’s fractured world. National leaders gathering at the UN general assembly this week face numerous daunting problems: among them, the authoritarian assault on democracy; record levels of conflict; pervasive flouting of human rights; impunity in the committing of genocide and war crimes; humanitarian emergencies exacerbated by foreign aid cuts; rising poverty; and environmentally damaging exploitation of less-developed countries’ natural resources.

Isolated, neglected, violence-wracked Myanmar suffers from all these ills. Viewed in this global context, it represents a test of the dwindling capacity of the UN-led system, regional organisations and “great powers” to maintain order and uphold shared laws and values. It’s a test they are failing miserably. And when it comes to China and Russia, and increasingly Donald Trump, the failure is intentional. As in many other so-called conflict zones, what is happening day after day in Myanmar is a largely un-observed, international disgrace. Myanmar holds up a mirror to a world of pain.

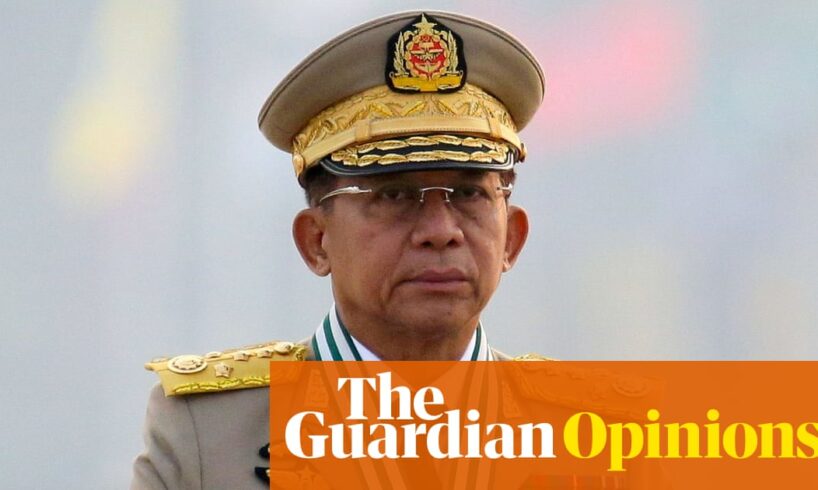

The ruling junta led by Min Aung Hlaing, an absurdly bemedalled Chaplin-esque dictator, is wholly illegitimate. Nationwide protests sparked by its overthrow of Nobel peace prize-winner Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy government were brutally suppressed. Rivalrous ethnic armed organisations subsequently seized large areas from the military – including much of western Rakhine state, where this month’s school bombing occurred. Undeterred, Min Aung Hlaing planning elections in December to rebrand his regime and cement his rule. It’s already clear that the polls, if they go ahead, will almost certainly be a travesty, their results likely fixed in advance.

Support from neighbouring China is key to the junta’s survival. As ever, Beijing prefers “strongman” rule to genuine democracy, prioritising state control, security and its infrastructure, energy and mining investments. President Xi Jinping welcomed Min Aung Hlaing, accused by international criminal court prosecutors of crimes against humanity, to his second world war anniversary parade this month. Exhibiting similar disregard for democracy and human rights in Myanmar, India’s leader, Narendra Modi, also embraced the dictator and backed his sham election. As chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), Malaysia insists a ceasefire must precede any vote. But Thailand and Cambodia have broken ranks.

The aftermath of an airstrike in Thayet Thapin village in Rakhine state, Myanmar, 12 September 2025. Photograph: AP

Further reflecting contemporary geopolitical schisms, Vladimir Putin’s Russia, which is the junta’s main arms supplier and has extensive experience of bombing civilians, is also closely aligned with Myanmar’s child-murderers. More surprising, and disturbing, is growing US ambivalence. Trump has sanctioned criminal gangs and ethnic militias that run junta-fostered scam centres, people trafficking and drug-smuggling operations. But in July, the US eased some restrictions, fuelling suspicion that, in return for Myanmar’s rare earth minerals, Washington may recognise the regime. This softening coincided with a lubricious letter from Min Aung Hlaing praising Trump’s “strong leadership”.

The suffering of Myanmar’s people knows no bounds. Thousands of civilians have died since the coup; thousands more are held without trial. Up to 4 million have been displaced and pushed further into poverty. After an earthquake struck in March, junta forces continued airstrikes, ignoring a supposed ceasefire and blocking emergency aid. Last month UN investigators said summary executions and the “systematic torture” of detainees, including burning of genitals, gang-rape, strangulation, beatings and electric shocks, were part of “a pattern of atrocities which is intensifying across the country”.

In addition, the plight of victims of an earlier crime – the Myanmar army’s genocidal 2017 pogrom that drove more than 700,000 mostly Muslim Rohingya residents of Rakhine state across the border into Bangladesh – grows steadily worse. Ongoing fighting, plus hate attacks by Buddhist-majority militia, have forced a further 150,000 Rohingya to flee since 2024. Now US and, prospectively, UK foreign aid cuts mean food and medical assistance is running out for the more than 1 million exiles in Bangladeshi camps. The UN refugee agency warns that by December, on current trends, there will be no food at all.

By almost any measure, Myanmar’s crisis is everyone’s crisis, reflecting the failings of a dysfunctional world. What is to be done? A special session of the UN general assembly next week will seek a “sustainable resolution” of the problems facing Rohingya and other Myanmar minorities. The EU and Britain, as UN security council Myanmar “penholder”, must do more; additional sanctions are imperative. Yet it remains unlikely that Asean or the US will adopt a more interventionist stance – or that China will suddenly see the light.

skip past newsletter promotion

Sign up to Matters of Opinion

Guardian columnists and writers on what they’ve been debating, thinking about, reading, and more

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain information about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. If you do not have an account, we will create a guest account for you on theguardian.com to send you this newsletter. You can complete full registration at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

On the contrary, Beijing is busy buying, indoctrinating and grooming tame political parties whose participation, it calculates, will make Myanmar’s coming election resemble a genuine contest. Poll “disruptors” face the death penalty. This is Xi Jinping’s big idea, his gift to humankind; this is the China model in action. As in Hong Kong, elections are fine, as long as the “right” people get elected. Myanmar is a pointer to the repressive, padlocked post-democratic world that awaits us all.

This is the future if the west fails. Like bombs dropping out of thin air, it could be over in a flash.