The “it” was an updated online application form, and news that information such as name changes through marriage – a key factor in many reunions – would now no longer be released without written consent from the parent.

While no laws have changed, practices around accessing names and addresses or siblings and informants will also be limited. As will the ability of groups such as Jigsaw and Link-Up to make sensitive approaches to suspected family – another often crucial factor in a successful reunification.

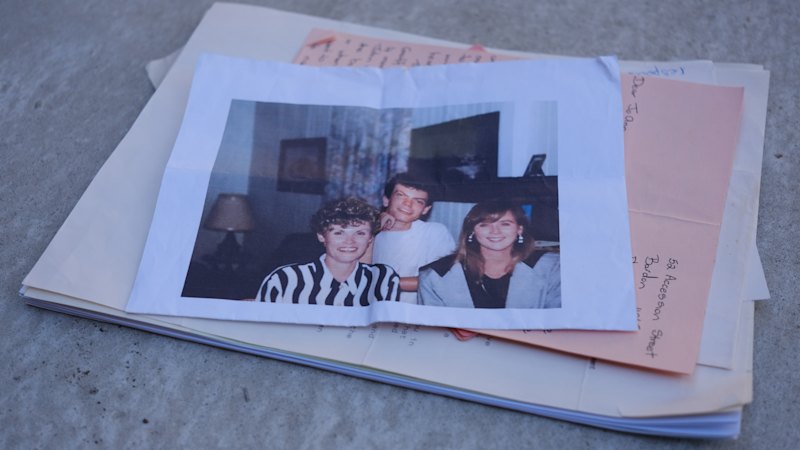

Dr Jo-Ann Sparrow, right, with her biological mother and brother on the day they met in November 1991Credit: Matt Dennien

After a raft of official state and federal government apologies for their roles in separating hundreds of thousands of families, such first contact will now have to be carried out by department officials.

“I mean, it’s ironic that no consent was needed to take these children from their parents, but now we have to have all these levels of consent suddenly to find each other,” said Sparrow, born at the peak of the forced adoption era in the early 1970s.

From her birthplace of Brisbane, Sparrow was adopted into a family with three existing biological children on the Darling Downs. She grew up feeling like she would never know her birth parents, but feels lucky she always knew she was adopted.

This knowledge drove her to be one of the first in line for information on her own biological family when it became available in 1991. Sparrow’s collection of documents and correspondence stemming from this also sits alongside a photo with her mother and brother on the day the met later that year.

Link-Up research manager Ruth Loli told this masthead in a statement that changes were “in direct opposition” to the Bringing Them Home report and principles endorsed by registrars nationwide, and was discriminatory to women.

“It is discriminatory to enable applicants to locate birth fathers or adopted sons but not to locate birth mothers or adopted daughters,” Loli said. Link-Up chief executive Patricia Thompson AM described the requirement for written consent from a parent “an appalling act”.

“This will only be triggering and re-traumatising for Aboriginal people, and with a lack of appropriate supports in place.”

Loading

Sparrow is calling on the government to reverse the change, with swift legislative changes if needed, and for meaningful consultation with the people and service providers impacted.

A letter from Jigsaw to Families Minister Amanda Camm has so far gone unanswered. Camm also declined to respond to questions from this masthead.

A departmental spokesperson would not be drawn on any specific catalyst for the change and whether other options were considered.

“We are committed to working with Queenslanders who are searching for information about their adoption,” the spokesperson said in a statement. “The department and the registry … have reviewed processes to ensure compliance with the legislation and privacy requirements for individuals involved in the adoption process.”

“As a result, the relevant form relating to requests for information from the birth entry register or adopted child register was updated to enhance privacy and compliance with the legislation. The Queensland government’s Commission of Inquiry into the child safety system, which is currently underway, will include a review of the Adoption Act.”

Even years on from government apologies and the end to the practices which sparked them, Sparrow says Jigsaw’s work is not slowing down.

If she were to start the search for her mother today – who married and changed her name twice – the current laws and practices “would not let me find her”.

“It would put things to a standstill and it would send me into the dark depths of DNA and internet searching, essentially, which … should be the option of last resort, not first resort,” Sparrow said.

“We should be able to have access to this information, just like other people in other states do, just like we’ve had right up until now.”