Open this photo in gallery:

PAUL DARROW/The Globe and Mail

When Donald Oliver was growing up in Wolfville, N.S., as part of the only Black family in town, racism wasn’t just a concept, it was a daily experience. He knew what it meant to walk into classrooms, grocery stores and restaurants and be treated as lesser.

A half-century later, when he swore the oath of office in 1990 as the first Black man appointed to the Senate, it meant more than recognition of his distinguished career and his community leadership. It carried the weight of history, proving that the walls that once shut him out could be broken.

Standing beneath the high ceilings of Parliament Hill’s Red Chamber, he finally had the power to shape the institution from within.

Mr. Oliver served 23 years in the Senate before retiring in 2013 at the mandated age of 75. Two years later, he was diagnosed with cardiac amyloidosis, a rare and fatal heart condition. His resilience and tenacity, combined with participation in a clinical drug trial at the Mayo Clinic, helped him continue his civic work for nearly a decade.

Even as the disease limited his mobility, he continued giving back to his community, mentoring and supporting young students in their pursuit of postsecondary education. He died at age 86 on Sept. 17 in Halifax, with his wife, Linda Oliver (née MacLellan), by his side.

Open this photo in gallery:

Donald Oliver outside of his office on Parliament Hill in Ottawa in October, 2004.Tobin Grimshaw/The Globe and Mail

His lived experiences were the fire that drove his work as a senator, lawyer, author, educator and founding member of the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia. His mission was always about creating change for Black Canadians.

“Senator Donald Oliver was a true pioneer, not only in his groundbreaking service to Canada’s Senate, but also in his dedication to our community here in Nova Scotia,” Russell Grosse, CEO of the Black Cultural Centre said in a statement.

Mr. Oliver was a strong voice against anti-Black racism. In the Senate, his fight for equal opportunities in hiring and employment went beyond speeches or motions. He personally raised $500,000 to design and lead a research study with the Conference Board of Canada that looked at the barriers visible minorities face in the public and private sectors.

The resulting report, “Business Critical: Maximizing the Talents of Visible Minorities,” became a guide for employers to identify and remove systemic discrimination.

He launched the Senator Don Oliver Black Voices Prize in 2023 to support emerging Black Nova Scotia writers. He also advocated tirelessly for employment equity. When asked in a 2010 Globe and Mail interview about why visible minorities were underrepresented in senior positions, his answer was frank: “I think it’s because of racism. I think it’s because of discrimination.”

In 2019, he was named a member of the Order of Canada. A year later, he received the Order of Nova Scotia.

After Mr. Oliver’s death, the province’s premier, Tim Houston, described him in a statement as a “courageous trailblazer,” who “proudly represented Nova Scotia for over two decades with grace, wisdom, and a relentless commitment to inclusion and justice.”

Open this photo in gallery:

Donald Oliver at Wroxton College in Oxfordshire, England in July, 2010.Jim Ross/The Globe and Mail

On Nov. 16, 1938, Donald H. Oliver was born into humble beginnings in Wolfville. His father, Clifford Oliver, and grandfather both worked as janitors at Acadia University. His mother, Helena Oliver (née White), was a talented pianist who earned her living as a seamstress. Donald, along with his four siblings and half-brother, faced endless discrimination as the only Black family in town. He once told former Globe and Mail reporter Jane Taber about his childhood experiences of being spat on and bullied; a waiter once told his family that they would not be served because they were Black.

He thrived academically, however, graduating from Acadia University in 1960 with a bachelor’s degree with honours in history, before earning his law degree at Dalhousie Law School in 1963 as a Sir James Dunn Scholar. He went on to have a distinguished career as a lawyer in civil litigation at Stewart McKelvey Stirling Scales for over three decades. He taught law at Dalhousie University and other institutions in Canada, the United States, South America, Scandinavia and London, England.

He also served as director of the Law Foundation of Nova Scotia and worked with more than 30 major charitable organizations and boards in Canada, rising to leadership positions in many of them.

Mr. Oliver’s political interest sparked during his undergraduate years at Acadia, where he was introduced to the Progressive Conservative Party and met former provincial premier Robert Stanfield.

He became a senior official with the Progressive Conservatives in 1972 and dedicated more than 50 years to the party. From 1972 to 1988, he oversaw legal affairs for six federal election campaigns.

Open this photo in gallery:

Donald Oliver on his farm in Pleasant River, N.S., in October, 2013.PAUL DARROW/The Globe and Mail

Mr. Oliver went on to represent Atlantic Canada as the party’s national vice-president and served as the director of the PC Canada Fund. At the provincial level, he served as the Constitution chair and member of the Finance Committee for Nova Scotia’s PC party, and later became the party’s vice-president.

In 1990, Mr. Mulroney appointed Mr. Oliver to the Senate, making him the second Black Canadian senator after Anne Cools, who was named to the Senate in 1984.

Mr. Oliver rose to become speaker pro tempore – the second-highest position in the Senate – in 2010 and held the position until his retirement in 2013.

Mr. Oliver’s final year in the Senate coincided with a scandal: 30 senators were accused of making improper expense claims. Three (Patrick Brazeau, Mike Duffy and Pamela Wallin) were suspended and one, Mac Harb, resigned. Mr. Duffy was tried on charges of fraud, breach of trust and bribery, and acquitted on all counts. Charges against Mr. Brazeau and Mr. Harb were eventually dropped, and the three suspended senators were reinstated.

A 2015 Auditor-General’s report recommended nine other senators – including Mr. Oliver, by then retired – for RCMP investigation. The RCMP ended their probe without laying charges against any of these nine senators.

Mr. Oliver repaid $23,395 in expenses, while maintaining that his claims were made “in the utmost good faith, and with an honest understanding of approval based on the guidance of Senate staff.”

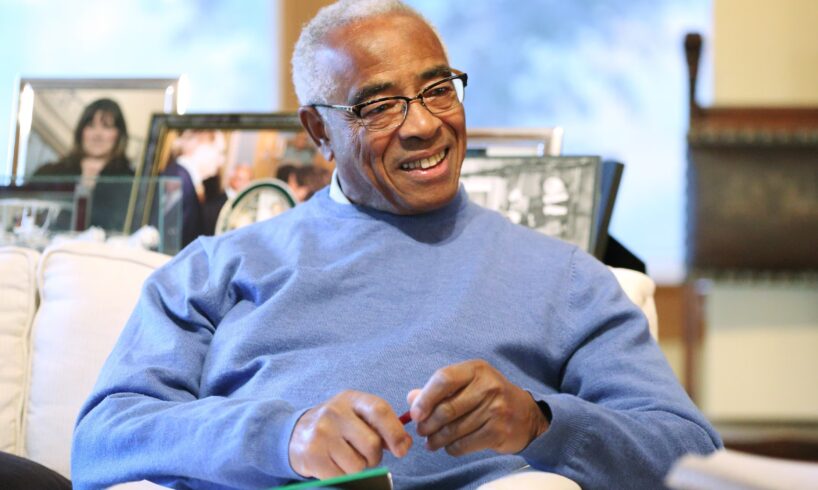

Open this photo in gallery:

Donald Oliver shows a photo taken with U.S. President Barack Obama in 2009.PAUL DARROW/The Globe and Mail

Despite the expenses investigation, Mr. Oliver’s former Senate colleagues remember him for his integrity. Mr. Duffy remembered him as a “rare and gentle man,” who was often a peacemaker.

“He had a good life and he did a lot of good for people. He set a very strong example of what it is to be a Canadian, not [just] a Black Canadian, but a Canadian,” Mr. Duffy said.

A Cordon Bleu-trained chef, Mr. Oliver enjoyed hosting dinner parties and wrote a cookbook, Men Can Cook Too! His farmhouse on the Pleasant River in Queens County, N.S., which he purchased in 1975 and restored after his retirement, became his sanctuary. There he cooked in his 700-square-foot kitchen he jokingly called “the West Wing,” gardened, listened to jazz, and entertained friends.

Mr. Oliver was admired by many prominent Canadian figures. In a statement, Prime Minister Mark Carney said Mr. Oliver had a “courageous life marked by committed service to his community and country.”

Over the course of his career, Mr. Oliver often spoke publicly about the barriers he faced as a Black man in Canada and the importance of removing them for future generations.

“His leadership was never about personal accolades. It was about uplifting others and ensuring no one was left behind – because doors had once been cracked open for him, he made it his mission to push them wide for other Black Canadians and marginalized communities,” said Senator Wanda Thomas Bernard, another trailblazing figure who joined the Senate following Mr. Oliver’s retirement and received his guidance as a mentor.

“May future generations see him as a model of leadership, rooted in heart, courage, and vision, a man who lifted others as he led the change he wished to see in Canada and beyond.”

Mr. Oliver leaves his wife, Linda Oliver, and their daughter, Carolynn Oliver.

You can find more obituaries from The Globe and Mail here.

To submit a memory about someone we have recently profiled on the Obituaries page, e-mail us at obit@globeandmail.com.