Transforming a major piece of Sydney’s public space from a former mental health hospital to an “iconic urban parkland” is a delicate dance for the state government.

Callan Park is a 61-hectare parkland in Lilyfield containing more than 130 historic buildings — many of which relate to a former psychiatric hospital.

Originally known as Callan Park Hospital for the Insane, the site was used for more than a century from the late 1870s.

During parts of its history, chemical restraint was common, and a royal commission found evidence of “cruelty” and little “active treatment or rehabilitation” being performed.

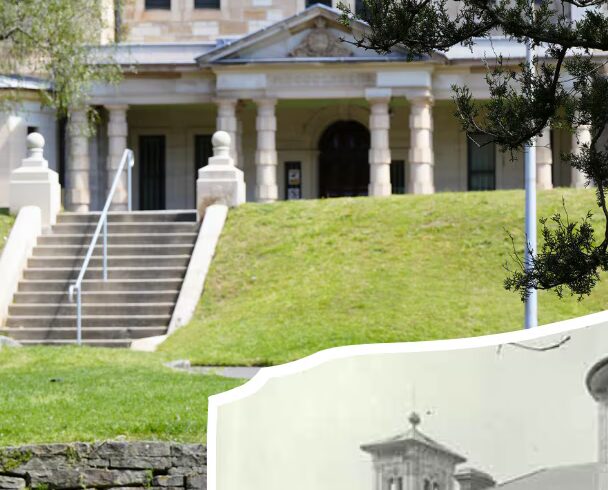

The Kirkbride precinct in Callan Park, previously associated with the psychiatric hospital, features multiple heritage sandstone buildings. (ABC News: Simon Amery)

A proposal to revamp the site includes restoring heritage buildings, welcoming film crews, and land use opportunities for cafes, markets, galleries and museums.

But legislation means development at Callan Park can only be carried out on a not-for-profit basis.

The Callan Park Act also prohibits the development of function centres, hotels or retirement villages on the site.

An artist impression of what a revamped Callan Park could look like under the state government’s proposal. (Supplied: NSW government)

A parliamentary review in June recommended commercial for-profit activity should be permitted in Callan Park.

Planning and Public Spaces Minister Paul Scully told the ABC the NSW government was “considering the recommendations”.

“The review found Callan Park’s legislation restrictive and recommended a number of amendments to enable further activations,” he said.

“We have seen some really great transformations across our public spaces.

“These activations have maintained the character and quality of the space, while making sure people have some fun things to do.”

With 300,000 Sydneysiders living within a 5 kilometre catchment of the park, many residents have fought for the maintenance and preservation of this “jewel of the inner west”.

Community groups wish to ensure Callan Park does not become commercialised. (ABC News: Simon Amery)

Community groups wish to see the heritage buildings restored for not-for-profit interests and organisations only.

The proposal remains on exhibition, with feedback to inform the final plans.

However, achieving a balance between respecting the sensitive history of archaic institutionalised sites while also revamping public spaces is not a new battle for stakeholders.

Storied past of original facility

A few suburbs over from Callan Park is one of Australia’s original psychiatric hospitals.

Gladesville Hospital, initally established under the name Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum. / Supplied: NSW State Records/ABC News: Isabella Ross

Overlooking Parramatta River, Gladesville Hospital’s historic buildings, cemetery and acknowledgement signs to those institutionalised reflect its storied past.

Initially established under the name Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum in 1838, Gladesville Hospital closed in 1993.

It was known for its sprawling grounds that were considered therapeutic for patients.

In its early years, the treatments offered for mental health care were considered “pioneering” for the time.

However, allegations of trauma and abuse emerged following the facility’s closure.

For some former patients, they view Gladesville Hospital as a “symbol of cruelty”. (ABC News: Isabella Ross)

Former patient Janet Meagher AM said the hospital remained a “symbol of cruelty” for her.

“That fear of return was so dominating, so terrifying that I was virtually paralysed to do anything,” she told ABC Radio National.

Well over 1,000 former patients remain buried at the site, mostly in unmarked graves, with the ages of those buried spanning from teenagers to 90-year-olds.

Gladesville Hospital is the final resting place of more than 1,000 former patients and some staff. (ABC News: Isabella Ross)

The Mental Health Commission of NSW held a memorial in 2019.

Now the 25 hectare heritage-listed site is owned by NSW Health and its buildings are mostly occupied by health service agencies.

The site’s grounds remain open to the public, with a foreshore green space called Bedlam Bay hired out by Hunter’s Hill Council for sporting and community events.

Site close to ‘many people’s hearts’

Hunters Hill Trust is a community organisation that for over 50 years has been advocating to preserve the area’s history and unique heritage.

For this group, the Gladesville Hospital site and its green space are precious for a multitude of reasons.

“It is a treasure trove of classical architecture, stone walls, formal gardens and vistas of early landscaping,” a trust spokesperson said, also pointing to the resonance of landmark mature trees throughout the parkland.

“It has so far resisted the ravages of modern development.”

The spokesperson said the trust regularly receives inquiries from members of the public who mistakenly think the group could help trace the history of relatives who were former patients at the hospital.

“We are therefore very conscious of how close this incredibly poignant site is to many people’s hearts, and we keep a watchful eye on any consideration of its future.”

Hunters Hill Trust members at Bedlam Bay, pictured left to right: Alister Sharp, Jim Sanderson, Annette Gallard and Maureen Flowers. (ABC News: Isabella Ross)

Acknowledging the wider push for new housing sites by the NSW government, the trust said it was “imperative” for residents to still have access to open green space, which was in the “best interests of public health and wellbeing”.

A NSW Health spokesperson acknowledged Gladesville’s “significant heritage value”, pointing to an ongoing program for remediation works including repairs and maintenance.

When asked if the department plans to maintain ownership of the site, the spokesperson said: “NSW Health is currently commencing preparations for a conservation management plan to guide the preservation and future use of the site.”

Commemorative signs on the site speak to its sensitive history. (ABC News: Isabella Ross)

From ‘obsolete’ hospital to university campus

Near Parramatta in Sydney’s west lies the former Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital site.

One of the hospital’s primary buildings was originally an orphanage for girls before it then became known as Rydalmere Hospital for the Insane.

Between 1888 to the 1980s, the facility had the intention of not just accommodating, but segregating people with mental illness.

The Rydalmere mental health facility was open for about a century. (Supplied: NSW State Records)

A 1949 Sunday Herald article reported there were only three doctors employed to care for over 900 patients, describing the conditions as “obsolete and inhuman”.

In the 90s, the former hospital grounds became Western Sydney University’s (WSU) Parramatta South campus.

“The university recognises and respects the rich history of the site, including its previous uses as an orphanage and psychiatric hospital. We are committed to preserving this important heritage,” a WSU spokesperson said.

The spokesperson said signage, artwork, exhibitions and public programming often commemorate the site’s past.

The former primary building of the psychiatric hospital now sits on a university campus. / Supplied: NSW State Records/Sally Tsoutas/Whitlam Institute

Conservation works on the complex were also undertaken and guided by Heritage NSW.

Sydney’s urban planners are all too familiar with juggling competing interests between residents, community groups and government entities.

Andrew Burridge, a senior lecturer in geography and urban planning at Macquarie University, said revitalising public green spaces presented a “fantastic opportunity”.

“Sydney’s population and density is only going to increase, so having access to large green spaces is fundamental,” Dr Burridge said.

“Commercial interests and overdevelopment are where the risk to public space potentially starts.

“Having NGOs, not-for-profits and educational or community organisations use these heritage structures is the more suitable option.”