“Hey, boneheads, how’s tricks? Time for a vicious assault on your morale. Here’s Bing Crosby.” During the Pacific Theater of World War II, American soldiers often found comfort in broadcasts like this one from Japan. They thought the female on-air voice which they nicknamed “Tokyo Rose” was soothing and sweet, yet laced with a playful sting that showed impeccable understanding of American humor.

The strange thing is that this wasn’t some brave operator sending out pro-American broadcasts from behind enemy lines. It was official Imperial Japan propaganda meant to lower the Allies’ morale. Instead, it had the opposite effect.

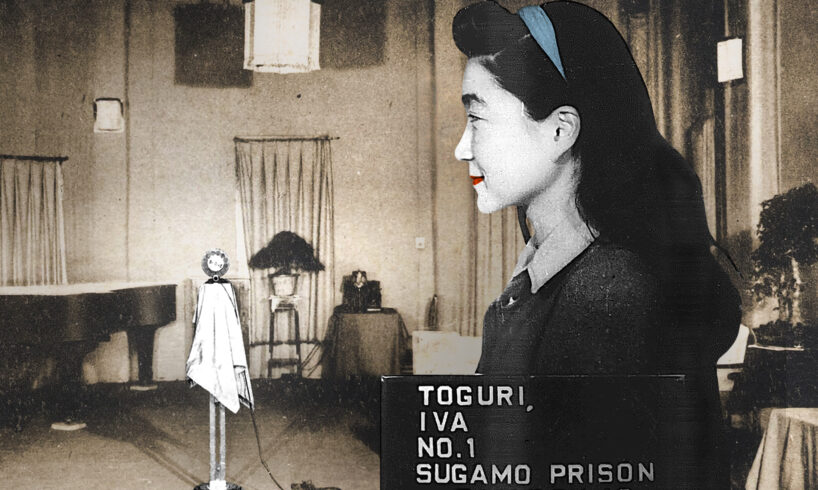

Toguri d’Aquino at Radio Tokyo, September 1945 | NACP

A Bouquet of Roses

Technically, Tokyo Rose did not exist. There was no single female radio personality operating out of Japan that addressed Allied soldiers in English. A number of women worked for Imperial Japan’s broadcast, The Zero Hour, on Radio Tokyo, but none of them took on floral sobriquets.

“Tokyo Rose” was a nickname wholly created by American servicemen, though some insisted that was how the announcer introduced herself. Many also claim that, between her playful jabs, she also told them upsetting things like how their wives were cheating on them back home. Those insults also didn’t exist — at least not in the broadcasts of the woman who helped create the idea of Tokyo Rose. Her name was Iva Toguri d’Aquino.

The Story of the Worst Vacation Ever

The daughter of Japanese immigrants, Iva Toguri d’Aquino was born Ikuko Toguri in Los Angeles in 1916. “Iva” was the name she adopted in high school. Raised Methodist, she loved swing music, played varsity tennis, joined the Girl Scouts and was fittingly born on the Fourth of July. The only way for her to be more American is if she could bake an apple pie that summoned bald eagles to her window sill.

After graduating from UCLA, she traveled to Japan in 1941 to visit an ailing relative, arriving just months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Stranded there, Toguri was branded an enemy alien and denied ration cards. Yet, whatever little food or medicine she managed to scrounge up, she shared it with American POWs she came to know. That’s just the kind of person she was.

It’s All in the Delivery

In 1943, due to desperation and coercion by the Japanese authorities, Toguri started working on Radio Tokyo’s The Zero Hour with other POWs, writing and reading scripts aimed to demoralize U.S. troops. She used nicknames such as “Orphan Annie” or just “Ann.” In 1945, she married Felipe D’Aquino, a Portuguese-Japanese man and became Iva Toguri d’Aquino. Again, she never called herself “Tokyo Rose.” However, she did take every chance possible to mock Japan’s propaganda.

In the scripts that they oversaw, Japanese authorities only noticed words of abuse like “boneheads” (one of Toguri’s favorites) and summaries of the terrible conditions from the front lines, so they OK-ed the broadcasts. “Ann” sprinkled them all with irony until they started coming off as endearing. On paper she was attacking Americans, but listeners were delighted by her fluent slang and deadpan sarcasm, and tuned into Zero Hour willingly.

Ann also tapped into the soldiers’ frustration with army life, often saying what they were all thinking. When she talked about bad army food and having to sleep in trenches, the reaction was, “Preach, sister!” The Zero Hour was, in a way, a release valve for the soldiers’ frustrations, and according to later FBI reports, actually boosted their spirits.

How Toguri Got Done Dirty

Toguri earned little money from The Zero Hour and reportedly shared what she could with American POWs. Combined with her clear mockery of war-time propaganda that only an all-American patriot could pull off, this should’ve earned her a red-carpet reception after the war. Instead, it got her arrested.

After being tricked into signing her name as “Tokyo Rose” for what she thought would be a well-paid tell-all interview, she was arrested for treason in Yokohama. The U.S. government investigated but transcripts of her Zero Hour broadcast showed nothing. No taunting, no leaks of military secrets, nothing treasonous at all.

A gossip columnist got wind of Toguri’s attempts to return to the U.S. and saw a chance to sell some columns at the expense of another person’s life. Radio host Walter Winchell stirred the public against Toguri, leading to her second arrest. This one stuck, with the surfacing of “evidence” that later turned out to be false. At the time though, it worked: Toguri spent six years in prison, was fined $10,000 and stripped of her American citizenship.

Radio host Walter Winchell (left) and Toguri d’Aquino interviewed by US correspondents, September 1945 | Wikimedia / NARA

A Long Road Towards Justice

In 1956, almost 20 years after Toguri’s release from prison, the truth about her involvement in the war came to light. Key witnesses recanted their previous testimonies, experts testified to her innocence and real reporters kept calling for justice. It was generally agreed that some English-speaking Japanese propagandists may have impersonated “Orphan Annie” because of her popularity, and they may have talked about unfaithful wives and bragged about U.S. ships being sunk by the Japanese Navy. Iva Toguri had nothing to do with that.

Finally, in 1977, President Gerald Ford granted Toguri an unconditional pardon and restored her citizenship. She remains the only U.S. citizen to overturn a treason conviction. The woman they called “Tokyo Rose” spent the rest of her life quietly and by all accounts happily — in Chicago, ultimately signing off the air permanently on September 26, 2006, at age 90.

Related Posts

Discover Tokyo, Every Week

Get the city’s best stories, under-the-radar spots and exclusive invites delivered straight to your inbox.

Updated On October 8, 2025