SINGAPORE: Nine-year-old Ethan (not his real name) has never once complained about going to school. Each morning, he heads off with enthusiasm and returns brimming with excitement, eager to share stories about his day.

But this year, a new challenge has tested him.

This is the first year the Primary 3 student had to sit for graded examinations. While he excelled in oral assessments – scoring 87 marks in one – he managed just 15 out of 100 in a recent written paper.

“Reading is very difficult for him so he can’t read the questions and he doesn’t really understand why exams are important,” said his mother, Jane (not her real name), adding that Ethan has a history of speech delays.

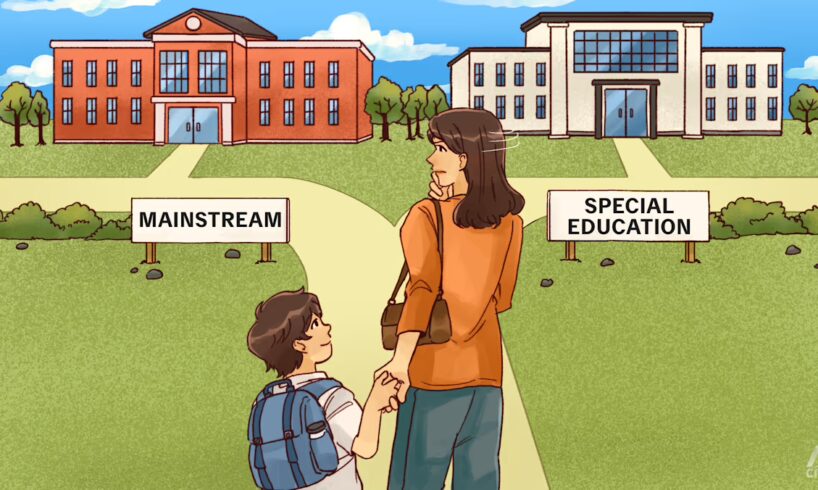

She now wonders if enrolling him in a mainstream school three years ago, instead of a special education (SPED) school, was the right decision.

Ethan was diagnosed with autism at age six and was recommended by the National University Hospital to be enrolled in a SPED school that offers the national curriculum.

“I cried when we got the results because we sent him for extra classes and gave him more learning support, but he was still struggling.”

Initially, Jane followed the doctor’s advice and applied to St Andrew’s Mission School, which caters to children with autism. But her application was rejected as Ethan was not yet able to read.

Determined for him to continue with the national curriculum, Jane enrolled him in a mainstream school in Bukit Panjang.

“We don’t want him to feel that he is different. My husband and I both work from home, so we felt we could teach him daily and guide him along,” Ms Jane said, adding that he has adapted well.

MORE CHOOSING MAINSTREAM PATH

Like Jane, a growing number of parents are opting to place their children with autism in mainstream schools rather than SPED institutions.

A study published in July in Singapore medical journal the Annals analysed medical records of children born between 2009 and 2011 who were referred to an autism clinic or diagnosed with autism.

Researchers reviewed demographic data, diagnostic methods, psychological assessments, early intervention attendance and school placement outcomes.

Of the 1,282 school placement recommendations recorded, 19.7 per cent were advised to attend mainstream schools, while 39.1 per cent were recommended SPED schools offering the national curriculum. The remaining 41.2 per cent were advised to opt for SPED schools offering a customised curriculum.

However, in practice, 45.9 per cent of the 1,483 children in the cohort ended up in mainstream schools, while 21.8 per cent enrolled in SPED national curriculum schools, and 32.3 per cent attended SPED schools with customised programmes.

Notably, 3.4 per cent of children placed in mainstream schools had originally been recommended for SPED customised programmes.

Dr Wong Chui Mae, principal investigator of the study and senior consultant at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, said the results mirror common patterns seen in clinical practice.

One factor influencing parental decisions, she said, was the limited availability of SPED schools offering the national curriculum. At the time, Pathlight School was the only such option. Since then, St Andrew’s Mission School has opened, and Anglo-Chinese School (Academy) is slated to launch in 2026.

During MOE’s budget debate in March, then-Second Minister for Education Maliki Osman said the ministry’s priority is to provide a good education for students with special education needs, regardless of school type.

He said mainstream teachers are trained to support diverse learners, and that students, teachers and leaders in SPED schools are given access to the same developmental support as those in mainstream schools.