25 Years Ago: UK rail privatization leads to fatal Hatfield crash

On October 17, 2000, a passenger train on the Great North Eastern Railway (GNER) traveling from London to Leeds derailed at 115 mph near Hatfield, United Kingdom. Four people were killed: Robert Alcorn, 37, of Auckland, New Zealand; Steve Arthur, 46, of West Sussex; Leslie Gray, 43, of Nottinghamshire; and Peter Monkhouse, 50, of Leeds; more than 35 others were injured. Some survivors escaped by crawling through shattered windows; others had to wait to be freed by rescue crews. The disaster occurred barely a year after the Paddington rail crash, which claimed 37 lives and injured over 400.

Early speculation in a media-driven frenzy about a terrorist attack proved unfounded. Once experts combed through the wreckage and interviewed survivors and rail workers, the evidence revealed chronic neglect of the tracks, leading to a fractured rail line. The company responsible for the privatized maintenance of the network’s tracks, signals, tunnels and bridges was Railtrack, created from British Rail in 1994.

A memorial garden for victims of the Hatfield rail crash

To contain public anger and protect its market value, Railtrack launched a damage-control campaign. CEO Gerald Corbett admitted the poor state of the tracks after the broken rail was identified as a key factor in the derailment. He offered his resignation, but the board, being notified beforehand about this public spectacle, refused to accept it, seeking to avoid a hit to share prices.

Evidence showed systemic negligence on the part of Railtrack. Faults on the Hatfield section were flagged as early as January 2000 and judged in need of renewal, yet repairs were delayed for nearly a year. Railtrack carried out temporary fixes, such as rail grinding, but a routine inspection just a week before the accident led to no action in fixing serious problems. Company officials claimed such delays were normal due to scheduling conflicts between train services and maintenance work.

The crash exposed the failure of privatization promises. Annual broken rail counts increased from 739 in 1996–97 to over 900 by 1998–99 and 1999–2000, despite Railtrack’s pledges to improve safety. Labour government assurances of investment and tighter regulation did not change the stubborn facts taken from the catastrophic crash: that profitability for investors took precedence over safety and that democratic control by railway workers over decision-making would have prevented such a disaster.

The Hatfield disaster starkly demonstrated the consequences of placing private profit ahead of passenger safety. On Britain’s privatized railways, the drive for returns to shareholders outweighed the most essential obligation to protect lives.

South Africa invades Angola with US backing

On October 14, 1975, the armed forces of South Africa’s apartheid regime, fully backed by US imperialism, launched an invasion of Angola. Codenamed “Operation Savannah,” the invasion was a desperate offensive aimed at destroying the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) before the country’s scheduled formal independence from Portugal on November 11. The goal was to oust the left-nationalist MPLA and install a puppet regime subservient to Washington and Pretoria.

The invasion came three months after the MPLA, which had widespread popular support among the impoverished Angolan masses, had successfully driven the CIA-backed National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) from the capital, Luanda. The MPLA had by this point already established itself as the new government. This victory threatened American plans to control the oil-rich and diamond-rich nation through its proxies, the FNLA and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).

South African Eland tanks [Photo by Sam van den Berg / CC BY 2.5]

The CIA’s “Operation IA Feature” had been financing and arming anti-MPLA forces since at least July. Washington was fully aware of South Africa’s invasion plans and actively assisted. A major airlift was organized to supply the invading forces. The invasion was an attempt to decapitate the MPLA before it could entrench itself as the sole legitimate government on the November 11 independence date.

The invasion began with several columns of the South African Defence Force (SADF) crossing into southern Angola from occupied Namibia. The main armored column, Task Force Zulu, advanced rapidly up the Atlantic coast, capturing the strategic port cities of Moçâmedes, Lobito and Benguela within weeks. With the objective of seizing Luanda before independence day, the South African forces, fighting alongside UNITA and FNLA troops, pushed hundreds of kilometers into Angolan territory.

Given that the South African forces were better armed with tanks and other armored vehicles, the MPLA was confronted with the threat of a military retreat from Luanda and losing control of the capital. The MPLA made an urgent appeal for assistance from its allies. In response, Cuba sent combat troops that began arriving in early November to bolster Luanda’s defenses. About 6,000 Cuban soldiers would aid in combating the imperialist siege of the city. Weapons supplies and about 1,000 military advisers from the Soviet Union were also sent to aid the MPLA.

The South African advance was ultimately halted by MPLA and Cuban forces just south of the capital in the Battle of Quifangondo on November 10. Faced with stiff resistance and growing international condemnation of the invasion, the SADF would begin a slow withdrawal. By January 1976 the South African forces would be forced into retreat and eventually pushed back across the border.

75 years ago: Imperialist forces capture Pyongyang, North Korea

On October 19, 1950, the Battle of Pyongyang concluded with a victory for United Nations (UN) forces, with soldiers from the United States Army marching into Pyongyang, the capital city of North Korea. It took place less than a month after US forces recaptured the South Korean cities of Incheon and Seoul, marking a turning point in the Korean War that had, up to this point, largely consisted of victories for the Korean People’s Army (KPA).

Preparations had already begun in the weeks prior for US forces to cross north over the 38th parallel, the latitude line along which US imperialism divided the Korean Peninsula at the end of the Second World War. The United States Joint Chiefs of Staff authorized UN Commander-in-Chief Douglas MacArthur to invade North Korea on September 29, the same day that US-backed dictator Syngman Rhee was reinstated as the South Korean president.

During the march to Pyongyang, US forces were joined by troops from the South Korean Army, who had already crossed into North Korea on September 30, making their way eight miles north of the 38th parallel within the next several days. Also accompanying the US Army were military units from Britain and Australia.

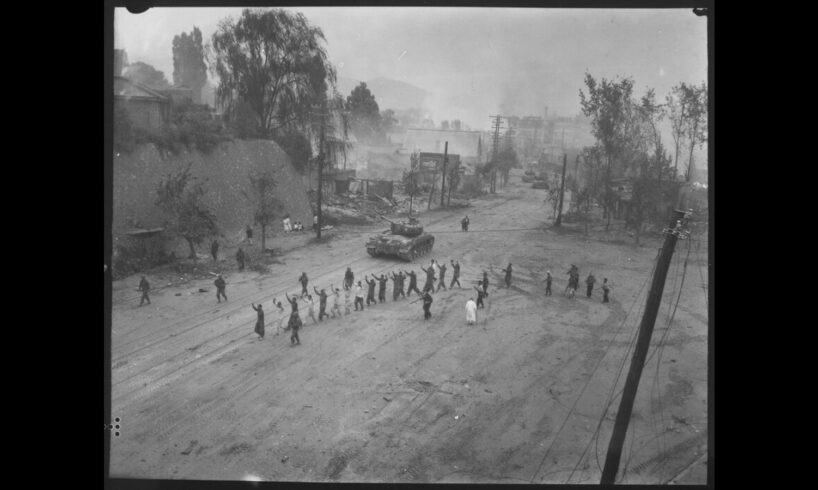

Captured North Korean troops after US forces enter Pyongyang

The Battle of Pyongyang itself consisted of three days of heavy fighting which began on October 17, when combined US and South Korean forces met with KPA defenses near the North Korean capital. US troops marched directly from the south while the South Korean forces flanked the KPA from the east. The North Korean military was unable to hold off this advance for more than a few days and swiftly retreated further north, as the government relocated to Sinuiju on the border with China.

The fall of North Korea’s capital to imperialist forces marked an escalation in the Korean War, which had already claimed tens of thousands of lives. MacArthur would soon after instruct his commanders to press forward to the Yalu River near the Chinese border, which was the precursor to China’s intervention into the war which would later bring Pyongyang back under North Korean control.

100 years: Syrian rebels take neighborhoods in Damascus from French

On October 18, 1925, in one of the key episodes of the Great Syrian Revolt against French imperialism which had begun in July, rebels under the leadership of Hasan al-Kharrat seized French strongholds in the capital of Damascus.

Guerrillas under al-Kharrat’s command had been harassing French troops in Ghouta, the green belt to the southeast of Damascus, since September, disarming troops and taking hostages. On October 18, 40 of his troops were able to infiltrate the ancient Al-Shaghur neighborhood of Damascus, where they were greeted by crowds of residents, many of whom joined the band. Together they captured the area’s police station and disarmed officers.

These fighters were able to seize and burn the Al-Azm Palace, the residence of the French High Commissioner Maurice Sarrail (who was not on the premises), in the Old City of Damascus.

Hasan al-Kharrat

About 200 troops of the nationalist politician and ally of al-Kharrat, Nasib al-Bakri, sealed off the entire Old City. About 180 French troops were killed during the action, and those remaining fled to the fortified Citadel of Damascus.

The French shelled civilian areas from the Citadel, including the commercial neighborhood to the south, called at the time Sidi Amoud but since 1925 been known as Al-Hariqa (The Conflagration), since it was completely burned down, as well as other neighborhoods. At least 1,500 Syrians were killed. While Damascus was eventually turned over again to the French, there was international condemnation of the massacre of so many civilians, and Sarrail was dismissed by the end of October.

Sign up for the WSWS email newsletter