Japan might hold the record for the longest use of crucifixion as a form of punishment in the history of the world. The ancient Romans crucified people for about 500 years, from roughly the 3rd century BCE until the practice was abolished in the 4th century CE. Japan had a much later start, with literary sources like The Tale of the Heike pointing to 1181 as an early reference.

However, one of the last recorded crucifixions comes from the 1860s, a few years before the punishment was abolished by the Meiji government. That marks nearly 700 years of killing people in one of the most brutal ways possible. Hard to imagine — in fact, nearly impossible — because Japanese crucifixion was very different from the Western kind. Here’s how:

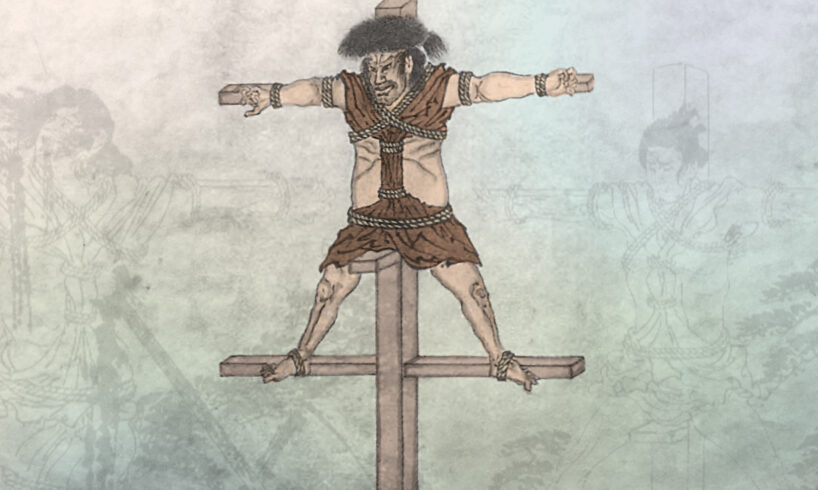

Depiction of an Edo period crucifixion by Naganori Sakuma | National Diet Collections, Wikimedia

For Display Purposes Only

The Japanese haritsuke crucifixion likely evolved from older punishments where offenders were bound to posts to be abused and humiliated by the community before execution. Haritsuke followed a similar model. Those convicted of particularly heinous crimes — like killing their master or parent, rebelling against the government or especially during the Edo period (1603 – 1867), forging money — were first given a “horsey ride.” This was the humiliation part. Called a hikimawashi, it involved parading the guilty through town on horseback with banners announcing their crime.

In later years, this was replaced by confining offenders in boxes with only their head poking out, and leaving them in high-traffic areas of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) for two days, where passerby could spit and jeer at them.

Only after that came crucifixion, although the practice used ropes instead of nails and a pole with two crossbeams, arranged like the katakana character ki (キ) for men. Women were crucified on the classic one-beam cross shaped like the kanji for “ten” (十).

Another important difference: the crucified didn’t actually die from doing lethal CrossFit. Once up on the cross, they were pierced with spears on both sides and had their throats cut, but only after hours of suffering from blood loss and stab wounds. The bodies were left up on the cross for a few days as a warning to potential criminals. If a person died from torture before crucifixion, the corpse was still displayed on the cross but only after being preserved in vinegar to delay decay.

Monument to the 26 Martyrs in Nagasaki, erected in 1962

Christians Had It the Worst

Haritsuke was most popular during Japan’s Warring States period (mid-15th century to early 17th century), though even then it wasn’t common. It was reserved for the worst of the worst and it took much time and effort. After the arrival of Christian missionaries in Japan in the 16th century, an odd coincidence was discovered: both cultures were obsessed with people on crosses. The practitioners of haritsuke were encouraged to continue.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537 – 1598), Japan’s second great unifier, had a particular fondness for crucifixion. After Christianity fell out of favor, he revived haritsuke on a grand scale, with mass executions and spin-offs like suitaku used to kill Christians. During suitaku, a haritsuke cross was planted by the coast at low tide, and as the waters rose, the condemned were slowly engulfed — the sea reaching just below their mouths without drowning them. There were no mercy killings here; death by suitaku could take days.

In 1597, Hideyoshi went back to basics when he ordered the crucifixion and spearing of 26 Catholics (both foreign and Japanese), in what became known as the execution of the 26 Martyrs of Nagasaki. Yet, unbelievably, the history of haritsuke grows darker still, so brace yourselves because things are about to get grim.

Not Just for Humans

There’s no easy way to put this, so we’ll just come out with it: there is a recorded instance of animals being crucified in Japan and not for killing their masters or for forgery, though you probably guessed that.

It began with Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, known as the “Dog Shogun,” a huge animal lover who issued the Edicts on Compassion for Living Things. The laws mandated severe punishments on anyone who abused animals, especially dogs, sometimes punishable by death. The Edicts may have had good intentions, but many people at the time resented the implication that dogs’ lives were equal to or even above theirs.

As a protest against Tsunayoshi’s law, the people of what is now Adachi Ward in Tokyo reportedly crucified two dogs in 1695 next to a sign that read: “These dogs have taken advantage of the Dog Shogun’s authority to torment people.” The act was meant to mock the government’s policies and while innocent animals had to suffer for it, at least the execution accomplished absolutely nothing. Tsunayoshi’s Edicts remained in effect until his death in 1709. There is no silver lining to this story, just senseless suffering as in much of history.