The land of possibilities

If Israelis had heard how the President of the United States spoke about the hostages, it’s doubtful that he would have received such thunderous cheers at Hostages’ Square last Saturday night. To say they were a secondary concern for him would be an understatement, and even that understates it. Donald Trump favored eliminating Hamas the American way, and 20 living hostages (he was always confused about their number and minimized it — I wonder what Sigmund Freud would have said) seemed to him a marginal matter, collateral damage.

Only belatedly did he perceive how strategic the issue was for the Israelis, and therefore for their government as well. In the United States, presidents have usually not been criticized for meeting hostages’ families too little, but for doing so too often (for details, search “Ronald Reagan” on Google).

In one of the discussions before Operation Gideon’s Chariots B began, Netanyahu spoke about the scar that would remain in Israeli society if Israeli forces conquered Gaza City at the cost of the hostages’ lives. Allow me to guess that he never really believed the moment would come.

Indeed, in recent months, Netanyahu and Ron Dermer’s perception was that an operation to conquer Gaza City, if it happens, might begin, but certainly would not reach completion. Here is the inside story.

Following the successful war in Iran, Israel tried to use the momentum to reach a partial deal. The idea was to release half the hostages and, during a 60-day ceasefire, arrive more or less at the conditions achieved this week. But Hamas, inspired by a Gaza starvation campaign that was gaining international traction, refused. President Trump, still in the shadow of Israel’s victory in Iran, thought the IDF could eliminate the remnants of Hamas as quickly as it smashed Tehran’s nuclear program. The combination of Hamas’ refusal and the president’s ambition led Israel to decide to enter Gaza City.

The idea was proposed by Minister Avi Dichter: conquering the city is the end of Hamas, he said at one meeting. The magic happened almost immediately: “Even before our forces entered the city,” Dermer recounted, “three days of talk about the operation did what three months of negotiations failed to do. Hamas suddenly agreed to a partial deal. But by then time had already run out.”

Israel faced two options: one, to conquer the remainder of the strip and establish a military government with American support. Dermer and Netanyahu believed that would require national unity and backing from Trump. The first component did not exist, and the second was highly unlikely.

The second option was a plan manufactured by Israel, led by the Americans, and supported by Arab states. President Reagan once told his people: you’ll write the plans, and I’ll be the presenter who markets them. This plan was no different, with Dermer filling the role of the writer. It was clear that any plan presented as purely Israeli would be pronounced dead before it was even born. That doesn’t mean every tweet was coordinated, the minister said at the cabinet meeting this week, but on the big matters, Jerusalem and Washington moved together.

Thus began arduous negotiations with Middle Eastern countries. During a round of talks in New York, it seemed impossible to get all those elephants into the same private room. Nevertheless, Israel’s representatives returned from there with 17 substantive comments from the Sunni states and even an agreement in the offing.

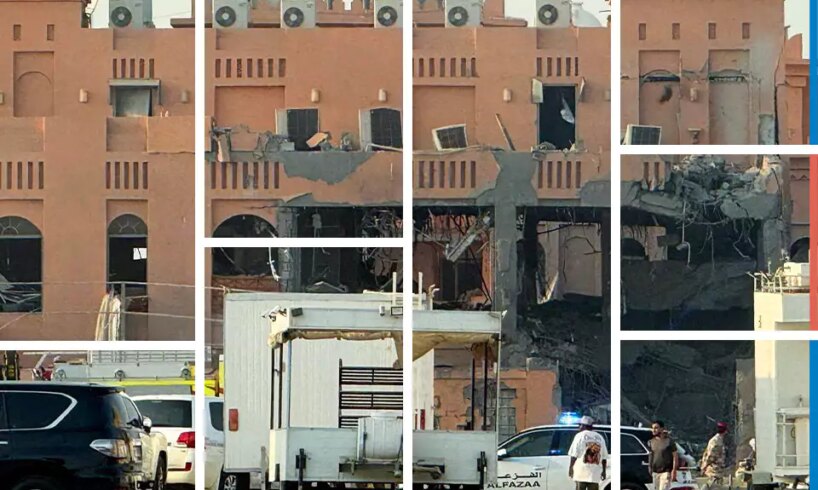

Then came September 9. Early in the morning, a three-person telephone consultation was held about the strike: Prime Minister Netanyahu, Defense Minister Katz, and Minister Dermer. All three supported the attack. Many issues came up in the consultation, but one particular issue did not: none of them believed there was an Israeli commitment to the Qataris not to strike Hamas personnel on their soil. Netanyahu called President Trump minutes earlier, but the president was groggy after a late night of discussions. It took time to reach him. The strike went ahead.

So far, it’s unclear how senior Hamas figures escaped the attack, but it’s obvious that it brought the deal closer. I recently wrote that it was the most successful failed assassination in history, in the sense that it signaled to the Qataris that the war would come to them if they did not stop their double game.

Dermer sees it differently. He links the strike to the agreement, but in a completely different way. The Qataris, it turns out, were convinced that by agreeing to host the negotiations, they had obtained immunity from Israeli strikes on their soil. From their perspective, the strike was a blatant, offense breach of the commitment.

Qatar had been unable to bring a deal for a long time, but it’s not half bad at thwarting deals. “The spoiler state,” they called it in Jerusalem — one that can easily ruin any agreement, as it did to the Egyptian hostage deal that was forming last spring behind its back.

Qatar is a complicated nation, Netanyahu said recently. What is it made of? In Jerusalem they describe two trains running behind the same engine. One, led by the ruler’s mother and brother, supports the Muslim Brotherhood and is an unmistakable hater of Israel. The other, led by the prime minister and several other senior figures, seeks rapprochement with the West.

Around April, a turning point was identified in Doha. Relations with the United States tightened significantly, and Hamas, an oddly patronized child, became a burden and a stain. All the Arab states rushed to assemble at the emir’s conference, both in anger at Israel and fear of a blue-and-white domination of the Middle East.

The Americans’ genius was to convert that negative energy into fuel to propel negotiations to their goal. “You want Israel to stop? Then let’s end the war,” they told the Sunni countries, and thus enlisted them in a framework that seemed impossible: a pan-Arab, almost pan-Muslim commitment to the elimination of Hamas. Dermer drafted the apology for the death of the Qatari security official; in Doha they reciprocated with a goodwill gesture by dramatically toning down Al Jazeera’s hostile tone.

More than enlisting them against Hamas, which had annoyed the entire Arab world, the achievement was to enlist them for a framework that does not include the Palestinian Authority in the foreseeable future. That is, for example, what held the Emiratis back from entering Gaza a year and a half ago. In one sense, that is the great innovation: before the plan, Gaza belonged to the Palestinian Authority; now it is Arab-international until further notice. The PA, meanwhile, hates Hamas so much that it agreed.

Yes, there will be a two-state solution, Dermer said this week. But not between the river and the sea — within the Gaza Strip itself. The plan is that as long as Hamas does not disarm, reconstruction will begin — but only in the half of the strip under Israeli control. What two years of war did not accomplish will be done by market forces: where will the population feel it is better to live — amid the ruins under Hamas boots, or in a rehabilitated area with an Emirati-funded school and a trailer home for each family?

The Americans believe this is a temporary situation, and are convinced that Hamas will be disarmed soon. Israel, of course, is much more skeptical. In a recent meeting, IDF Chief of Staff Eyal Zamir made a request of the Americans: Explain to me please. Your multinational force, with a few battalions, enters a tunnel. Hamas operatives are armed there. How exactly does this disarm Hamas? Who exactly will hand over the weapons? And what if they don’t?

You didn’t believe the first phase would happen, the Americans said, believe that the second will happen too. Have a little faith, the Jews with an American flag on their lapel told the Jews with an Israeli flag.

Fog, of war

Many unforeseen things have happened in the past month. Here is another October surprise: when the Knesset plenum returns this coming Monday, a bill to dissolve the Knesset will not be on the agenda. A legal opinion determined that because the bill failed last summer, 61 signatures are required to reintroduce it soon. The ultra-Orthodox were supposed to join, if only to threaten Netanyahu. But then the ceasefire deal arrived, and the opposition didn’t even try. They understood there was no chance that Shas chairman Aryeh Deri would support it in such an historic moment. After all, he is no Yitzhak Goldknopf, who equates the return of hostages from Hamas captivity with the return of IDF deserters from Israeli prison.

The prime minister still wants to postpone the elections as long as possible — at least that’s what he says in private. The reason? First of all is history: Netanyahu has split from partners and prompted early elections only once, during the hated Bennett-Lapid government. His playbook is that one day of rule in the hand is better than two in the bush — especially now, when peace agreements with Muslim countries are just around the corner. According to assessments, they will not help bring in a caretaker government and want to build a plan that is viable for years to come. What they do not want is to serve as material in an election campaign.

So if Netanyahu wants to delay the elections, why doesn’t he give Deri and Moshe Gafni his famous treatment, which includes endless talks, meetings and not-so-mild physical pressure? After all, Shas seems to be dying to return to the government.

Maybe he’s delaying the move because he was busy, then ill. And maybe, just maybe, he wants the two or three weeks of quiet he’s just received to examine his options. If the polls show a dramatic turn in his favor, and if it becomes clear that the conscription law is still unpopular even during relative calm, it may be worth going to elections at the end of winter. And if — as after Iran — the needle does not move, the incentive to wait until the final moment will grow. In short, as the Bank of Israel buys dollars for a rainy day, Netanyahu is buying time.

Avinatan Or alongside his parents after his release. Photo: IDF Spokesperson’s Unit

LIght and shadow

Now that all the living hostages and all the excuses have been exhausted, the time has come for the State of Israel to make the decision it has been comfortable fleeing from for more than two years: the death penalty for the Nukhba murderers. First, so that they will not be released in the next deal — whenever it comes. But primarily, because that is what justice demands.

It is unpleasant to be a country with the death penalty, but the thought of financing this band of murderers is even less pleasant. The excuse that this would encourage terror seems ridiculous after one of the deadliest days of terror in world history. If there is no real change in every aspect of the struggle against Hamas, there will be no change in their actions toward us. What is needed is a public trial in Nir Oz, glass cells, and gallows.

*Many hostage videos were released in the past year. The vast majority were published on Saturday afternoons, shortly before the rally in Hostages’ Square and the demonstration on Kaplan street began. It is interesting to note two hostages of whom videos or photos were never published: Avinatan Or and Eitan Mor, the former from Shiloh and the latter from Kiryat Arba.

Hamas knew very well that the two families would not agree to broadcast even a single second filmed in the tunnels, faithful to the consensus at the start of the war: do not cooperate with Abu Obaida’s psychological warfare. It was not wrong, of course: the Or family was the only one to vet those calling them during the bizarre video calls on the morning of the release.

Can a democratic state forever impose self-censorship on itself? Highly doubtful. For that reason, there is no point in legislating the recommendations of the Shamgar committee that forbid the mass release of terrorists and even meetings between the prime minister and hostages’ families. One does not decree a measure the public cannot tolerate.

And yet, there is surrender, and there is surrender. The Or and Mor families set the proper standard under terrible conditions. It is a shame that the national radio stations, one funded by the government and one by the army, did not learn from them: instead of opening every hour with “We won’t stop until everyone returns,” they should have added: “We won’t stop until victory.” The government set two objectives for the war, the stations it funds decided there is only one.