Abby-Lee Honeysett remembers Gulgong as the sort of place where kids would ride their bikes until the streetlights came on.

That was until the day in 1999 when 17-year-old Michelle Bright was murdered.

Just nine years old at the time, Ms Honeysett vividly recalls the impact it had on the western NSW community.

“Living and being outside all changed for us when Michelle was murdered,” she said.

Michelle Bright, 17, was walking home from a friend’s birthday party when she was murdered in 1999. (Supplied)

“As a child, watching your family try to navigate sudden heartbreak, grief and loss was confusing and intense.”

The case remained cold for nearly two decades, until Craig Rumsby was found guilty of the teenager’s murder in 2023 and sentenced to 32 years behind bars.

Ms Honeysett said her mother Kim was like a sister to Michelle’s mum Loraine Bright.

The stories she heard around the kitchen table about Michelle’s case and the coronial system stayed with her, eventually inspiring her to change careers.

After a decade as a teacher, she returned to study and graduated with a Bachelor of Medical Science from Western Sydney Univerisity.

“I discovered that grief from a murder is uniquely devastating, and it can linger for years and the turmoil disrupts your daily life,” she said.

Turning grief into purpose

Now 36, Ms Honeysett works as a forensic mortuary technician at NSW Health Pathology’s Forensic Medicine Service in Lidcombe, a role that places her at the heart of stories that end too soon.

She assists pathologists with post-mortem examinations for unexplained, violent or suspicious deaths, prepares loved ones for identification, and helps families through one of the hardest days of their lives.

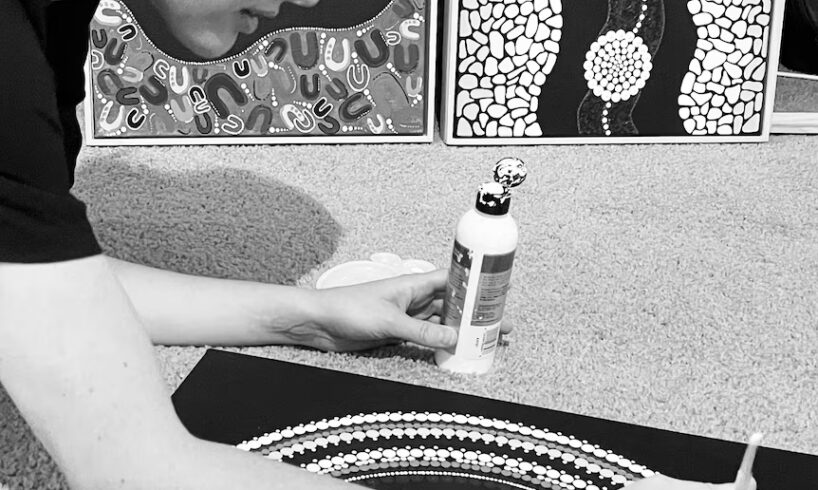

Abby-Lee Honeysett says painting not only helps her disconnect from work but connects her to culture. (Supplied)

Ms Honeysett said it was Michelle’s case that had shaped her work.

“Michelle’s family had a horrific time while she [her case] was being navigated through the coronial system, and those stories stuck with me,” she said.

“I just want to be that support system, and advocate for everyone that comes through my care at the Coroner’s Court.

“I want to be the voice that they don’t have, because Michelle never had that.”

For Michelle’s mum Lorraine Bright, seeing her daughter’s legacy honoured through Ms Honeysett’s work has been deeply moving.

“It makes me so proud to see Michelle’s memory live on,” she said.

“It shows the type of person she was, and that she was loved by so many people and nobody is forgetting her.”

Healing through culture and art

Ms Honeysett has also found another outlet that helps her disconnect from work and reconnect with culture.

“Being exposed to death and trauma does take its toll mentally, so when I get home from a long day at work I just get lost in time while painting,” she said.

Abby-Lee Honeysett created Birrang, which means “journey”. (Supplied)

The Wiradjuri woman said it was not until later in life she reconnected with her culture, a process now deeply woven into her art.

“To me, Aboriginal art is a visual language, it tells a story so it helps me express my identity and fosters a sense of belonging, especially since moving to the city, it helps keep me grounded,” she said.

“It helps me keep the visual stories alive and express my connection to country.

“I grew up on Wiradjuri country so the connection to land is greater than connection to water, so a lot of my artworks depict some aspect of contemporary landscape design.”

One of her recent works, Healing Together, now hangs in the foyer of Grace’s Place — a residential trauma centre for children and families affected by homicide.

“The circular design was very intentional,” Ms Honeysett said.

“Grieving is not a linear process. I witnessed there are ups and downs, you can be really good one day and you can hit rock bottom the next.

“It’s got winding pathways connecting communities together and the pathways weaving into the centre, which is Grace’s Place.

The painting was auctioned and donated to Grace’s Place, to raise money for the Homicide Victims’ Support Group.

“Honestly that’s where this painting belongs, it couldn’t go to a better place,” Ms Honeysett said.

“My heart and soul went into this painting, it’s very personal, and I just wanted to keep Michelle’s legacy alive.”

For Ms Bright, the artwork carries a deep connection with her daughter Michelle.

“The colour purple was specifically placed throughout because it was her favourite colour,” she said.

“Abby and her family, specifically her mum Kim, have all gone through the loss of losing Michelle too.

“I am just such a proud mum knowing Michelle’s legacy is providing a visual representation of love and healing to those affected by homicide.”