The Warring States (Sengoku) and Azuchi-Momoyama periods, lasting from roughly the mid-15th century to the first years of the 17th century, were a time when both the emperor and shogun lost all authority, and real power lay with regional warlords vying for dominance. It was when Japan essentially operated on prison yard rules. Every samurai with an army wanted to be thought of as the toughest, meanest guy around to protect their lands and family, and that required making an example of anyone who crossed them. And when warlords really wanted to hammer home the message that they were not to be trifled with, they put the hammer down and instead reached for the saw.

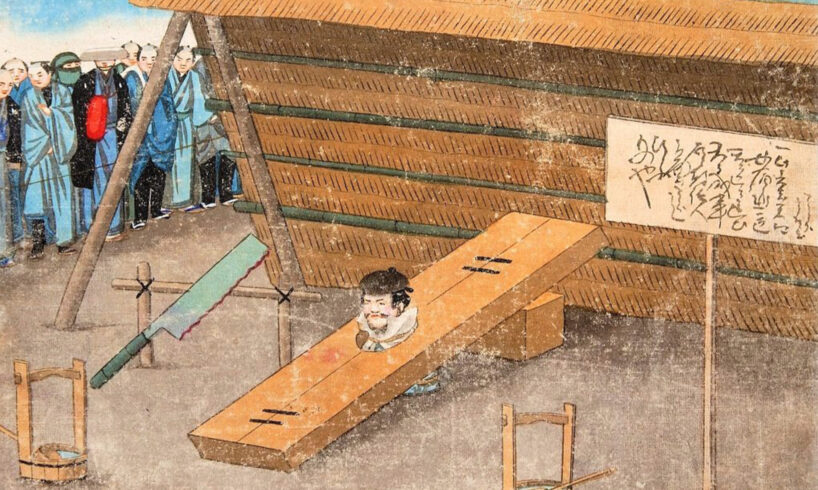

Depiction of nokogiribiki in “Illustrated Guide to the Punishments of the Tokugawa Shogunate” by Fujita Shintaro (1893) | Wikimedia

What the Executioner Saw and Sawed

“Nokogiribiki” simply means “sawing,” and as an execution method, it was exactly as advertised: killing a person with a saw. The practice might have originated in the Heian period (794–1185), but it really took off in the 1500s. From the very beginning, it was a public spectacle, where someone convicted of the worst crimes imaginable (like killing their master) was literally… “made less” by executioners with bamboo or metal saws. In the most extreme cases, the process could last days.

Execution by nokogiribiki became increasingly involved as time went on, and eventually, the process included an element of public shaming and, more horrifically, family participation. In later incarnations of the execution method, the condemned was placed in a box with just their head sticking out or was buried up to their neck. Then, members of the public — or even the condemned’s family members — were “encouraged” to take a saw and make small cuts along the screaming head’s neck.

Since the neck is a tight cluster of veins and arteries that, if severed, would cause a quick death — and end the execution prematurely — we can assume that amateurs were only making symbolic, superficial cuts, doing more psychological damage than anything else. The actual punishment was carried out by an experienced executioner who knew how to slowly saw off a head while keeping the victim — there’s no other word for it, no matter their crime — alive as long as possible.

Depiction of Oda Nobunaga by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1830) | Wikimedia

Who Would Be Cruel Enough to… Of Course, the Demon King

Oda Nobunaga, the first great unifier of Japan, kick-started the process of mending a broken country in order to bring stability and prosperity to the realm. But because he was the first, he had the hardest job ahead of him and apparently felt that cruelty was the most viable option going forward. Nobunaga wasn’t a monster: He was a person who loved the tea ceremony, and sumo, and noh theater. He also gave himself the intimidating nickname “Demon King of the Sixth Heaven” to taunt his deeply religious rivals. But it’s hard to argue that he did not earn the moniker as time went on.

Besides massacring 20,000 people, including women and children, at Kyoto’s Mount Hiei and burning another 20,000 alive at the Nagashima Honganji temple complex, Nobunaga was also responsible for one of the most infamous cases of nokogiribiki. In 1573, Nobunaga was almost assassinated by Sugitani Zenjubo, one of the first snipers in Japanese history (and a suspected ninja), who ultimately only managed to graze the Demon Lord. He ran, but he didn’t get far. According to the Shincho Koki chronicle, “Sugitani was punished in a way Nobunaga had specially designed: He was buried upright to his shoulders, and then his head was sawed off. Thus Nobunaga dispelled his long-felt anger.”

There are recorded cases of nokogiribiki from before Sugitani’s death, like that of Wada Shingoro, who was executed in 1544 for having an affair with a lady-in-waiting of high status. He first had his arms sawed off and then was beheaded, but that was apparently done quickly, or at least not artificially prolonged. It is possible that the Demon King invented the nokogiribiki variant of slowly sawing off a head; it would be very on brand for him.

Execution depicted in the “Illustrated Guide to the Punishments of the Tokugawa Shogunate” by Fujita Shintaro (1893) | Wikimedia

When Crucifixion Was a Mercy

Sawing people alive actually stuck around well into the Edo period (1603–1867), but at some point, public opinion turned against the slow torture-death. This was most likely because the Edo period was a time of peace and prosperity, when people liked focusing less on public executions and more on perfecting the art of being cool. Eventually, executioners started refusing to carry out a nokogiribiki sentence, thinking it too cruel. Also, it took up all of their day, and that’s time they could’ve spent reading books about Edo (modern-day Tokyo) prostitutes.

So, by the mid- or late Edo period, a compromise was reached. People still got put in a box or buried in the ground, and they still got cut up a bit with saws, but it was more of a ritual, a bit of theater before the real, comparatively humane execution commenced: crucifixion. Unlike Western crucifixion, the Japanese variety involved stabbing the condemned once they were up on the cross so they would bleed out. It could take a few agonizing hours before the final throat cut put them out of their misery, but compared to nokogiribiki, it really was the less cruel alternative. Still absolutely horrific, though. It’s almost like there isn’t a good way to take another person’s life.

Related Posts

Discover Tokyo, Every Week

Get the city’s best stories, under-the-radar spots and exclusive invites delivered straight to your inbox.