WARNING: This story contains graphic content and vulgar language.

Part 1: ‘Crazy, crazy criminality’

When Arron Linklater leaves his house, the essentials come with him: Wallet. Phone. Keys. Bullet-proof vest.

For 30-odd years, Linklater has been dealing cocaine in Dawson Creek, a small town tucked within the sprawling farmland in northern British Columbia at the origin point of the Alaska Highway.

Although he lives in a modest bungalow, Linklater boasts that his cocaine business can bring in hundreds of thousands of dollars a month. In all that time, the RCMP has only busted him once for drug trafficking.

A member of the nearby Carrier Sekani First Nation, Linklater has deep roots in town. His grandfather was Dawson Creek’s mayor in 1951, during its first major population boom thanks to the area’s first gas plant and the arrival of the Pacific Great Eastern Railway. In those days, a Linklater didn’t have to worry about being shot while walking through town.

But this is no longer his grandfather’s Dawson Creek.

Death, by the needle or by the bullet, now stalks its streets.

“He’s turning in his grave right now,” Linklater said of his grandfather. “I’m his only grandson who would carry the Linklater name on. He’d just say: ‘You’re a f–king idiot.’ He’d probably slap me.”

Alaska Avenue, also known as B.C. Highway 97, which flows into the Alaska Highway, runs through Dawson Creek. The town finds itself besieged by a wave of killings and crime that has lasted more than a year. (Timothy Sawa/CBC)

Linklater has watched the town evolve from a farming community into a booming oil-and-gas region that spawned more clients for his wares. With more money came more drugs, from cocaine to fentanyl. And more drugs meant more crime and violence.

There have been 13 unsolved homicides in four years — 11 since January 2023. Like justice, an end to the killing seems elusive in the town of 12,500 souls.

For more than a year, the fifth estate has been investigating this cyclone of crime, answering an email from a viewer desperate for attention and help. Last year, the RCMP told the fifth estate they expected “some level of success” within six months in what were then investigations into 11 unsolved killings in Dawson Creek.

Watch the full documentary, “Dawson Creek: Behind the Fear,” from the fifth estate on YouTube or CBC-TV on Friday at 9 p.m.

The fifth estate discovered the justice system has been unable to keep the worst criminals off the streets and has found more connections between the killings and the local underworld.

While police say they remain confident they will make progress in some of those homicide cases, the killings have continued.

“Get investigators here that will do something about it, get rid of the drug dealers,” said resident Laura Lambert, whose two nieces are among the slain. “We want our kids back.”

In 2024, the RCMP said they would have ‘some level of success’ in solving some of the killings of these 11 people in Dawson Creek. To date, no arrests in any of these cases have been made. Top row, left to right: Lance Patterson, an unidentified male, Bryon Horne, Rob Girbav. Middle row, left to right: Tina Nellis, Adam Roy Isely. Bottom row, left to right: Chris Engman, Dave Domingo, Darylyn Supernant, Renee Supernant Didier, Cole Hosack. (Tim Kindrachuk/CBC)

In the absence of justice, Dawson Creek is gripped in rumour and fear. Everyone has a theory about who is killing whom and why.

“I think the biggest misconception here is knowing and proving are two completely different things,” said RCMP spokesman Staff Sgt. Kris Clark.

The rumours are sometimes fuelled by threats on social media with a singular message — opening your mouth might be the last thing you ever do. One of those threats came as recently as Thursday, as the fifth estate was preparing to broadcast its most recent investigation into the killings in Dawson Creek.

On Oct. 29, as the fifth estate prepared to broadcast its latest investigation into the killings in Dawson Creek, Jesse Ray Stevens — the half-brother of Tanner Murray, one of the town’s most notorious criminals — posted this message to his Facebook page, railing against ‘rats who talk.’ (Jay Remy/Facebook)

Not even those responsible for pushing drugs onto the streets of Dawson Creek are safe. When the RCMP came to Linklater’s door in the spring to tell him about threats made against his life, he reached for his Kevlar.

But he won’t leave town.

“I ain’t gonna f–king hide. I’m gonna stand in broad f–king daylight and I don’t really care where you live, what you do for a living, I don’t care who you think you are,” said Linklater.

Like many in town, Linklater has his own theories to explain the rising tide of crime. But before Linklater could expound upon them for the fifth estate, he needed to engage in his relaxation ritual — a snort of a few lines of cocaine and a swig from a bottle of vodka.

Last year, the RCMP devoted more resources to stem what they called “gang-related violence” in Dawson Creek. The idea makes Linklater laugh. There is no gang war in Dawson Creek, he said. Crime is of the decidedly unorganized variety, he said. Local drug dealers who don’t get along kill each other and those they find inconvenient.

And then there are those who have fallen through the cracks in town.

“The minute you put a gun into [the hands of] a fetal alcohol, Down syndrome kid who’s never f–king had to earn his penny in his life, but he’s fought from every corner he’s ever been, and he has no chance and never did, you get the worst criminality,” Linklater said.

“You get crazy, crazy criminality.”

Arron Linklater, left, who said he was a career cocaine dealer, talks with the fifth estate’s Mark Kelley, right, about crime and killings in Dawson Creek. (Ousama Farag/CBC)

Just how “crazy” can be found in the data. The town’s homicide rate is 14 times the national average, according to Statistics Canada. Overdoses in town increased five-fold from 2016 until 2023.

In this environment, safety in town appears elusive for criminals and regular townsfolk alike. Residents complain criminals are arrested, but rarely spend much time in jail. People vanish without a trace. The lives of addicts crumble, with some becoming armed agents of a desperate chaos. No one seems able to stop any of it.

Welcome to Dawson Creek.

WATCH | The drugs are rampant in Dawson Creek:

Criminality in Dawson Creek

Career drug dealer Arron Linklater describes why Dawson Creek, B.C., is a hotbed of crime and killing.

Part 2: ‘The funeral people couldn’t put him back together’

Dawson Creek’s official tourism website paints an idyllic portrait of the town. There are hiking trails, a farmer’s market, swing dance lessons and the iconic street sign marking Mile Zero of the Alaska Highway.

“The Dawson Creek culture is very laid back and fun,” says DawsonCreek.com. “It’s a small town, it is a tight-knit and family-oriented community.”

That isn’t the town Jan Atkinson has come to know intimately. But she wanted to.

An outreach worker by trade, Atkinson left Kelowna, B.C., for Dawson Creek in 2017 to escape the wreckage the opioid crisis had caused there. She was looking for respite in the family-friendly town and, for a time, she found it.

But soon Atkinson found a wreckage of a different kind.

“I think things were really set off with the first murders of Tina and Roy,” said Atkinson. “I think after that it really spiralled.”

Adam Roy Isley and Tina Nellis were slain in January 2023 in a trailer at the Mile Zero Trailer Park.

Adam Roy Isley, left, and Tina Nellis, right, were killed in a Dawson Creek trailer park in January 2023. Their deaths, still unsolved, were the first in a wave of killings in town that year. (RCMP)

Isley was in his mid-20s when he began earning a six-figure salary in the oil-and-gas industry. It was that career that eventually brought to the town.

Everything changed after he arrived in Dawson Creek, his family said. Isley was caught in the undertow of Dawson’s Creek’s drug culture. His marriage broke down and he started using street drugs. In this new life, Isley began to go by his middle name, Roy, and his burgeoning fortune vanished with his career prospects.

“He went from making big money to making no money,” his father, Quinten Isely, said.

More than two years later, he doesn’t know why his son was killed. Sources in town told the fifth estate he and Nellis were killed over unpaid drug debts. But the RCMP, Quinten Isely said, has told him “absolutely nothing.”

What Isely’s family does know is that his death was incomprehensibly brutal.

“They said you couldn’t have an open casket,” said Quinten Isley.

“The funeral people couldn’t put him back together again,” said Isley’s sister, Rachel Janke.

WATCH | A brutal death:

‘Couldn’t put him back together’

The family of Adam Roy Isley describeS what they know about his killing.

The deaths of Isley and Nellis marked the start of the bloodiest year in Dawson’s Creek’s recent memory and were part of an unprecedented wave of crime unlike anything the town had seen in decades.

According to Statistics Canada, which produces an analysis of crime labelled “the crime severity index,” in 2023 Dawson Creek had a serious crime score 3.5 times higher than the national rating.

Statistics Canada measures serious crime in Canadian cities and towns. The rating for Dawson Creek is significantly higher than the national figure. In 2023, a year in which nine people were killed, the rate was more than three times the national level. (Tim Kindrachuk/CBC)

“It’s always been a kind of Wild West. It has been rough. It’s always rough,” said Andy Tylosky, a life-long resident of the Peace River region, which includes Dawson Creek.

“But the people just disappearing in the unexplained, burnt-out vehicles and things is just … it’s not something that we do in Canada.”

After the incident at the Mile Zero Trailer Park, seven more people would be killed in 2023.

Seven more families are still waiting for answers. Among them are the families of cousins Darylyn Supernant and Renee Supernant Didier, who were both killed that year.

Darylyn Supernant’s father, Brad Supernant, told the fifth estate last year she had been shot in the head because she witnessed a double homicide.

Outreach worker Jan Atkinson says she knows which killings they were.

“Darylyn had come to me and told me … that if anybody hurt her, who it was,” said Atkinson. “It was just all in relation to the original killing of Tina and Roy.”

Darylyn Supernant vanished from Dawson Creek in March 2023. Her body was found nearly a year later in a ditch near town. Her father believes she was killed because she witnessed the killings of Tina Nellis and Roy Isely in 2023. (Darylyn Supernant/Facebook)

When Darylyn vanished in March 2023, her family began to search, including her outspoken cousin, Renee — who also vanished in December 2023. Asking questions about her cousin might have been enough to get her killed, her family said.

Their bodies were found in the spring of 2024, Darylyn in a ditch and her cousin close to the Kiskatinaw River, 30 kilometres northwest of Dawson Creek.

According to their families, near the end of their lives both women were talking to the same person — a man whose name many in Dawson Creek won’t speak aloud. Tanner Allan Murray.

As the fifth estate investigated Dawson Creek, Murray’s name came up over and over again, connected to guns, drugs and violence.

Tanner Murray, seen here in a 2023 RCMP mug shot, has been convicted of gun, drug and assault charges. According to the families of Renee Supernant Didier and Darylyn Supernant, Murray was in contact with them just before they disappeared. (RCMP)

Darylyn was preoccupied talking to Murray on her phone the last day her stepsister saw her alive. And the day Renee vanished, she was in a hotel room with him.

Another cousin, Shyann Hambler, tried to reach Renee by video call that day.

“Tanner Murray did answer Renee’s phone, and I’m not going to back down from saying it,” said Hambler.

Although she stands by her story, Hambler — who said she left Dawson Creek for a time because of threats to her life — would say nothing else about Murray.

“No comment,” Hambler said when asked by the fifth estate’s Mark Kelley if she believes Murray had something to do with Didier’s death.

“Are you afraid that commenting on that could get you more death threats?” Kelley asked.

“Yes,” said Hambler. “One hundred per cent.”

Shaynn Hambler, dressed in Cree regalia, stands in a cemetery in Dawson Creek to remember her slain cousins, Darylyn Supernant and Renee Supernant Didier. Both women were in contact with Tanner Murray shortly before they vanished, according to their families. (Timothy Sawa/CBC)

Murray is an infamous criminal in Dawson Creek who has cast a shadow over the town. He has not been charged in either homicide, but his past makes him the prime suspect in the minds of many people around town.

The fifth estate was unable to reach Murray.

CBC News also reached out to more than a dozen people who know Murray. Most would not speak about him, and those who did would not say much.

“I think he’s mostly just instilled a real sense of fear,” Atkinson said.

Murray’s long rap sheet goes back to 2021 and includes convictions for assaulting police officers, drug trafficking, possessing illegal firearms, robbery and more than a dozen violations of parole and bail conditions. Murray has been in and out of custody at least five times and often returns to the streets of Dawson Creek.

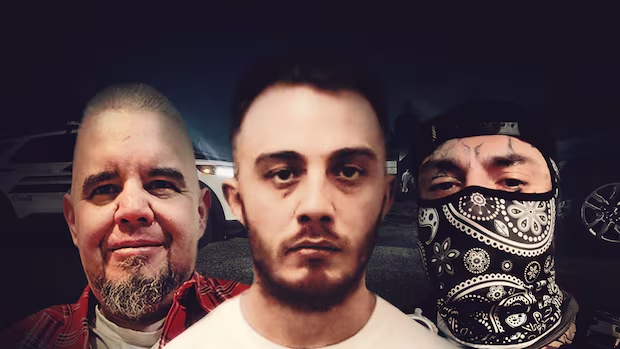

He is closely linked with his half-brother, Jesse Ray Stevens, a man with a face covered in tattoos who was charged with attempted murder in 2023. That charge was dropped in 2024 after the Crown’s only witness refused to testify.

Murray’s criminal career marched onward in 2024 and included an arrest on more than a dozen gun and drug charges. After his arrest, the RCMP warned Dawson Creek they couldn’t keep Murray behind bars.

“Police have applied to keep Tanner in custody, however, it is expected he will be released back into the community,” said an RCMP media release.

Renee Supernant Didier vanished after searching for her missing cousin, Darylyn Supernant. Her body was found in 2024. Her family believes she was killed because she was asking too many questions about what happened to Supernant. (Renee Rose/Facebook)

Part 3: ‘Blood’s gonna be on your hands’

The new year was less than a month old when the all-too-familiar crack of a muzzle blast marked a new killing in Dawson Creek. On Jan. 20, 2025, Joel Johnny Freeman became the town’s 12th homicide victim in four years. This time, though, the RCMP laid a murder charge.

But the arrest of 23-year-old Nolan Schmidt did little to tamp down fears in the community. He was a known whirlwind of trouble who was expected to meet a bad end — or end someone badly.

“I had written a letter to the judge being like, you know, blood’s gonna be on your hands,” said Atkinson, the local outreach worker who was once Schmidt’s case worker at a Dawson Creek homeless shelter. “My fear is that he would murder somebody.”

Although Schmidt has been in and out of jail for years, often for weapons or drug possession charges, he is not a criminal kingpin. Some men, like Linklater, profit from the drug trade. Others, like Schmidt — addicted, angry and spiralling — are the creations of it.

Atkinson’s fears about Schmidt were not the first time a Dawson Creek resident had reason to fear the release of a dangerous person. One of the town’s most well-known criminals, Tanner Murray, has repeatedly violated his release conditions while on bail or parole.

The failure of the police to bring the chaos to heel has eroded the townsfolk’s faith in the justice system, turning people away from the police service that is supposed to protect them.

“Until we can trust the system, people aren’t going to have trust in coming forward,” said Jan Atkinson, the longtime outreach worker. “Nothing is going to happen.”

Nolan Schmidt poses on top of a fire hydrant in Dawson Creek in 2024. Schmidt is facing a second-degree murder charge in the 2025 killing of Joel Johnny Freeman. (Douglas Devine/Facebook)

Schmidt portrayed himself with a gangster flare on his Facebook page, where he goes by the alias Douglas Devine. And Douglas Devine, as it happens, is friends with Tanner Murray.

On his page, he shows a tattoo over his heart in memory of his mother, Kelly Schmidt, who died of a drug overdose in 2014.

“He found her,” said Andy Tylosky, someone who knows Schmidt. “It just wrecked him. He totally lost his sense of hope.

“He told me at the funeral, he just started drinking because that was the only way that it kind of numbed the pain. And he never really stopped.”

Kelly Schmidt with her then young son, Nolan, in an undated photo from his Facebook page. Kelly Schdmit died of a drug overdose in 2014, an event that shattered a teenaged Nolan Schmidt, says Andy Tylosky. (Douglas Devine/Facebook)

Tylosky believes hopelessness lies at the heart of the town’s troubles.

“Having that lack of purpose or having lost a sense of why they are here or what their purpose in life is overwhelms people,” he said. “And that’s how we end up with a situation like Dawson Creek.”

In the winter of 2023, Schmidt — frequently using street drugs, according to court records — went on a crime spree, assaulting his aunt, threatening to kill her and trying to rob a cabbie in town.

Initially released on bail, Schmidt violated his conditions, at one point threatening Atkinson, resulting in his rearrest.

At the behest of the RCMP, Atkinson wrote two letters to the court imploring it not to release Schmidt.

“I am begging the courts to remand Mr. Schmidt into custody,” she wrote.

WATCH | A plea to the judge:

‘Blood on your hands’

An outreach worker in Dawson Creek, B.C., talks about her encounter with Nolan Schmidt.

Schmidt was denied bail, but when his sentencing hearing came a few months later, he was released with time served after being convicted of assault, threatening bodily harm and possession of a firearm. He served six months in jail, while the maximum sentence he could have been given was two years.

As part of his parole, Schmidt was to reside with Tylosky, who thought he could provide the young man with the means for a fresh start.

But the arrangement was fraught from the start. Tylosky said what money Schmidt had was consumed in his crack pipe. Thirty-five days after he was released, Tylosky accused Schmidt of stealing money. Schmidt threatened him at knifepoint. The RCMP defused the situation, but much to Tolosky’s surprise, two hours later Schmidt was once again a free man.

Tylosky knew he could no longer help Schmidt and last saw him when he dropped him off in Dawson Creek near a homeless shelter.

Two days later, Joel Johnny Freeman lay dead, Dawson Creek’s 12th homicide since 2021. Another man, shot in a room at the Mile Zero Hotel shortly after Freeman was killed, survived.

RCMP officers arrested Schmidt and charged him with aggravated assault and second-degree murder — the first murder charge the RCMP laid in 12 killings.

Freeman and Schmidt were not strangers. Tylosky thinks Schmidt believed Freeman gave his mother the drugs that ultimately killed her.

Schmidt had pleaded not guilty and remains in custody awaiting trial.

Joel Johnny Freeman was killed on Jan. 20, 2025. Nolan Schmidt has been charged with second-degree murder. Freeman became the 12th killing in four years in Dawson Creek (Joel Freeman/Facebook)

Part 4: ‘Pull the trigger’

By the fall of 2025, Arron Linklater was feeling the squeeze. He was four months away from standing trial on five counts of drug trafficking — the first time in his career as a dealer that he faced a real risk of prison time. Threats against his life were ramping up

“I’ve been threatened after you guys left. I was threatened to, like, a bizarre level,” he said in a September phone call with the fifth estate producer Timothy Sawa.

Sawa and the fifth estate co-host Mark Kelley had visited Linklater in June. By September, he was being threatened in connection with the town’s latest killing.

“Is this related to the Emily Ogden thing?” Sawa asked.

“Yeah, but that even isn’t my responsibility either,” Linklater said. “That’s not me.”

“But does someone think it’s you?”

“Absolutely. The whole community does.”

Emily Odgen was a 24-year-old who became homicide victim No. 13 in April 2025. She had been missing nearly a month before her body was found on a rural road near Dawson Creek inside a pickup truck. Linklater and Ogden knew each other, but were far from friends. In February 2024, Linklater was in his home, on his knees, while he and his daughter stared down the barrels of several shotguns.

Emily Ogden from a 2022 Facebook photo. Within two years of this photo being taken, she would fall into Dawson Creek’s criminal underworld, taking part in a home invasion and then becoming the town’s 13th homicide victim in April 2025. (Emily Ogden/Facebook)

A masked gang lured Linklater to his door by claiming they were RCMP. After they burst in, he was forced to the ground at gunpoint.

To try to protect his daughter, Linklater said he tried to distract the posse who wanted drugs and money.

“I grabbed their shotguns and pulled them towards me and said, ‘F–king pull the trigger, pussy. If you can’t kill me now, you weren’t coming here to kill me in the beginning.’” One member of the gang stood behind Linklater and laughed.

“There was a girl … she’s laughing at me. I’ll never forget that laugh” Linklater said. “It’s this stupid ass person who thinks they can laugh at you for threatening to kill your daughter over a few ounces of drugs.”

It was Ogden.

Like Nolan Schmidt and Roy Isley, Ogden’s sad tale is one of a person transformed as she descended into the maw of the town’s drug trade. Like them, she began to associate with some of the players in Dawson Creek’s underworld, including the crew that raided Linklater’s home. Not in that gang was Odgen’s sometime boyfriend, Tanner Murray.

The gang in Linklater’s house slashed his face with the barrel of a shotgun and threw him down the stairs.

“I didn’t cry, I didn’t moan, didn’t bitch about none of it,” Linklater said. “I had an idea that, OK, I signed up, bro. You’re not gonna whine about it now.”

There was no cash or drugs for the posse on that day. They stole Linklater’s truck and made their escape. They did not get far. Ogden and two other people were arrested. Linklater’s truck was returned to him.

Ogden was out on bail when she vanished in March 2025. Her body was found in Linklater’s truck a month later. Linklater said his truck had been stolen a second time and he did not know anything about Ogden’s death. He was out drinking when she was killed, he said.

Linklater was brought in for questioning by the RCMP and released. He considers himself to be the “prime” suspect.

Linklater says he was brought in for questioning regarding the killing of Ogden, who was found dead in his truck months after she took part in a brazen home invasion of Linklater’s bungalow. Linklater, who said he was the ‘prime’ suspect, denies involvement in her killing. (Ousama Farag/CBC)

Part 5: ‘I don’t live scared’

In April 2025, Tanner Murray was holed up in a Dawson Creek motel hiding from police.

The RCMP were looking for Murray. They had a warrant for his arrest after he violated his parole conditions following that 2024 drugs and weapons bust. Police caught up with him in May, but not in his stomping grounds of Dawson Creek.

Just across the B.C. border in Grande Prairie, Alta., Murray and two others were arrested in possession of a guitar case filled with drugs, a drug weight scale and guns, including a semi-automatic rifle, a modified hunting rifle, a shotgun and a Glock 9-mm pistol, along with hundreds of rounds of ammunition.

He was denied bail and remains in custody on weapons and drug charges, with a pre-trial scheduled for June 2026. The fifth estate has been unable to reach Murray.

After he was arrested in Grande Prairie, Alta., police charged Tanner Murray with a host of gun and drug charges after they seized this guitar case filled with weapons and drugs. Murray has been denied bail and is awaiting a pre-trail hearing that is scheduled for June 2026. (RCMP)

Linklater told the fifth estate that the RCMP informed him that Murray and his brother, Jesse Ray Stevens, were making threats against him.

In March, Stevens posted a photo of himself masked and pointing a Beretta pistol at the camera to his Facebook page.

Then in May, a week after Murray’s arrest in Alberta, Stevens posted a childhood photo of the pair and wrote how he “told everyone not to f–k with my brother.”

Stevens posted again on Oct. 29, complaining about “rats who talk and talk.”

“It’s your ass,” Stevens wrote.

Tanner Murray’s half-brother, Jesse Ray Stevens, posted this image of himself as his Facebook profile photo in March. The RCMP and residents in town believe the image is a direct threat to people in town. (Jay Remy/Facebook)

The RCMP say the posts were not benign.

“I can’t speak to his state of mind, obviously. I don’t know what his intent is other than the words he’s presented, but that appears to be a direct threat,” said RCMP spokesman Staff Sgt. Kris Clark.

The threats got worse in September, Linklater said. He sent his family away as a precaution, and now they live in a place with an ocean view and sand between their toes.

Linklater refused to flee.

“I’m not scared of living. I don’t live scared. Fear’s a choice.”

Four days after his phone call to the fifth estate producer Timothy Sawa, teams of RCMP officers surrounded Linklater’s house.

They were not there to arrest him. Linklater was removed from his home by forensic officers on a stretcher, in a black body bag.

The RCMP investigated Linklater’s Dawson Creek home in September. Inside they found Linklater’s body. A week later, the RCMP began to investigate his death as a homicide. (Timothy Sawa/CBC)

Police initially said there was no foul play involved, but a week later, the RCMP major crimes unit arrived at the house. Linklater’s death was now considered a homicide. They have not said what changed their focus or released the cause of Linklater’s death.

In his June interview with the fifth estate, Linklater said a popular method of assassination in Dawson Creek involves spiking a person’s drugs with carfentanil, an opioid 10,000 times more potent than morphine. Even a tiny amount of the drug can be lethal and may make a homicide look like an overdose.

“It’s an assassin’s drug,” he said. “If somebody owes some f–king massive amount of money, that’s all it takes to fix the problem, a little carfentanil.”

It was the third homicide of the year and the 14th unsolved killing since 2021 in Dawson Creek.

The RCMP continue to say they believe they can solve some of these cases.

Clark, the RCMP spokesman, said police cannot make a bust based on rumour. They need hard evidence.

“We can say that: ‘We know this person did it.’ But we need to prove that in a court of law and successfully prosecute that so that the families of the victims do get that justice.”

WATCH | It does not take much to kill someone:

‘An assassin’s drug’

Career drug dealer Arron Linklater explains how carfentanil is used as a tool of killing in Dawson Creek, B.C.

Postscript

The job of finding justice got even harder for the RCMP on Oct. 16. On a remote patch of road known as Deadman’s Curve, near the Kiskatinaw River, north of Dawson Creek — the same area where Renee Supernant Didier was found — a body was discovered in a burned-out car.

The victim of homicide No. 15 has not been identified.

No arrests have been made.

If you or someone you know is struggling with substance use, here’s where to look for help:

If you’re affected by this story, you can look for mental health support through resources in your province or territory.