Shafaq News – Baghdad

A death sentence handed

down by an Iraqi court against a Syrian national convicted of terrorism has

unsettled the country’s large Syrian refugee community and reignited debate

over how Iraq balances justice, security, and social cohesion in the post-ISIS

era.

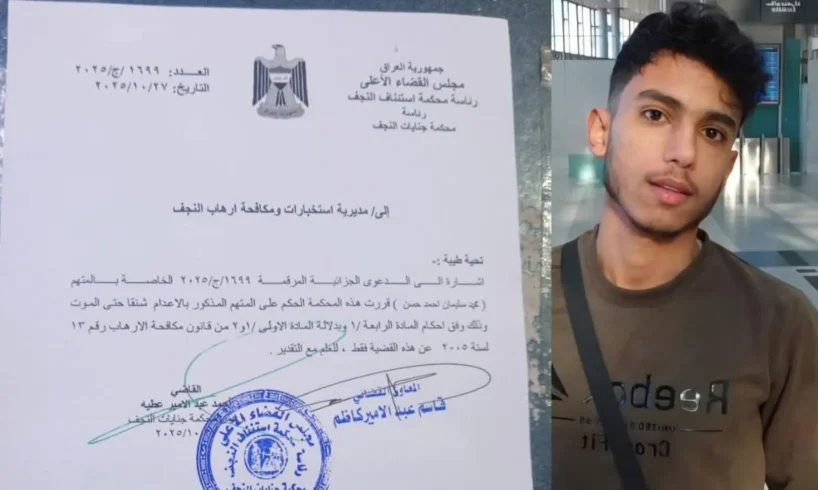

The Najaf Criminal

Court sentenced Mohammed Suleiman Ahmed, a Syrian citizen, to death under

Article 4 of Iraq’s Anti-Terrorism Law, which prescribes capital punishment for

those found guilty of committing, assisting, or financing terrorist acts. The

court said the ruling followed full legal procedures and a confession from the

defendant.

While the judiciary

defended the verdict as due process, its impact has reverberated far beyond

Najaf, stirring fear among Iraq’s roughly 250,000 Syrian residents, many of

whom worry that one man’s crime could taint an entire community.

Refugees Fear

Backlash

In Baghdad, where

tens of thousands of Syrians work in trade, construction, and small industries,

the case has sparked anxiety about collective blame.

“We respect Iraq’s

courts and trust their fairness,” said Mohammed al-Halabi, a Syrian merchant

who has lived in the capital since 2015. “But we fear that online campaigns

could stigmatize Syrians because of one man’s actions. Most of us live and work

here with dignity.”

Similar concerns

emerged in Kirkuk, a city already marked by political and ethnic strain. “We

live among Iraqis as brothers,” said Omar Abdullah, a Syrian clothing trader.

“But this verdict created unease. We fear hostility or misunderstanding,

especially in areas already on edge.”

Even in the Kurdistan

Region, where Syrian refugees generally enjoy greater legal and economic

stability, apprehension grew. “Relations between Syrian and Iraqi Kurds are

strong,” said Samir al-Qamishli, a resident of Erbil. “But the news reminded

people how vulnerable refugees remain to political shocks.”

Between Law and

Public Perception

Legal experts view

the Najaf ruling as consistent with Iraq’s counterterrorism framework, but

acknowledge its political and social sensitivities.

According to Iraqi

officials, who spoke to Shafaq News, the challenge is maintaining trust between

communities, pointing out that the Syrian population here is diverse—workers,

traders, families—and “none should be judged through the lens of one case.”

Under Article 4,

enacted in 2005, thousands of defendants have faced the death penalty for

terrorism-related crimes. Iraqi officials argue the law remains essential for

deterrence, while rights groups say it relies too heavily on confessions and

lacks sufficient judicial oversight.

The verdict’s timing

and visibility have amplified its sensitivity. Many Syrians in Iraq have spent

over a decade rebuilding their lives after fleeing war and economic collapse at

home. According to the Interior Ministry, about 180,000 Syrians hold valid

residency permits, while humanitarian organizations estimate that tens of

thousands more remain undocumented because of legal and financial obstacles.

Tensions Spill Toward

the Border

The ruling coincided

with a separate incident near the al-Bukamal border crossing, where four

Iraqis returning from Syria were reportedly robbed and assaulted by armed men

“believed to be Syrians,” local sources told Shafaq News. The attack raised

fears of reprisals or resentment linked to the Najaf verdict.

A security official

in al-Anbar Province urged calm, saying to Shafaq News that the assault

appeared “criminal rather than retaliatory.” He added that Iraqi forces had

tightened security along the frontier to prevent escalation. “The al-Bukamal attack

does not represent Syrians as a whole,” the official said.

The Iraqi–Syrian

border—stretching more than 600 kilometers from Sinjar in Nineveh Province to

al-Qaim in al-Anbar—remains one of the region’s most volatile frontiers,

patrolled by Iraqi border guards and Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) amid

ongoing concerns about smuggling and residual ISIS activity in the desert belt

between the two countries.

Fragile Coexistence

Most Syrians in Iraq

have become integral to the urban workforce yet continue to face bureaucratic

hurdles, social prejudice, and economic vulnerability. Many now fear the Najaf

ruling could harden public attitudes or embolden discriminatory rhetoric

online.

“The court’s decision

shouldn’t reflect on thousands of Syrians living legally in Iraq,” said Ahmed

Abd al-Rahman al-Dimashqi, a food trader in Baghdad. “We are guests who respect

the law and contribute to this country’s economy. One person’s crime shouldn’t

define an entire community.”

Though limited to a

single case, the Najaf sentence has become a prism through which Iraq’s broader

post-war dilemmas are refracted: how to enforce justice without deepening

divides, secure borders without inflaming prejudice, and uphold the rule of law

while safeguarding fragile coexistence.

Written and edited by

Shafaq News staff.