Shafaq News

Iraq prepares for its parliamentary elections on November

11, 2025, and the promise of democracy faces its toughest test — not inside

parliament halls, but in the alleys where desperation often speaks louder than

conviction.

In a nation where poverty and politics often overlap, the

boundary between choice and necessity is fading, leaving many Iraqis to view

the ballot not as a tool of change but as a means of survival.

Cards for Cash

In a modest Baghdad neighborhood, Um Dua, 60, handed over

her voter card to a campaign representative in exchange for a small bag of food

and 100,000 dinars (about $76) — barely enough to buy her medicine.

“I needed money to buy my prescriptions,” she told Shafaq

News. After receiving the payment, she surrendered her card and decided not to

vote at all. “I expect nothing from the candidates,” she added quietly.

Around her, the scene has become routine. As elections draw

near, the narrow streets of the capital’s poor districts fill with campaign

vehicles and emissaries seeking voter cards. The offers vary — cash, food, or

monthly stipends — depending on the district, the candidate’s influence, and

even the voter’s age.

For 22-year-old Raaed Al-Aboudi, the transaction came with

better terms. “One campaign official offered me $200 in exchange for my card,

to ensure my loyalty on election day,” he recounted to Shafaq News.

But Al-Aboudi decided to negotiate. “I asked for fixed

monthly payments of no less than 150,000 dinars (about $114) until the

elections, and they agreed. It became a steady income for over two months,” he

shrugged, saying such practices have become customary among voters, especially

the youth.

Read more: Financial muscle: How money shapes Iraq’s upcoming elections

Ballot Card Futures

What happens in Baghdad’s alleys is part of a larger,

carefully organized trade — one that turns voter cards into political currency.

Abu Abdullah Al-Saadi, who helps manage campaign promotion

for a list in the al-Rusafa district, described how it works. “Campaigning is

not easy, especially for new candidates who are unknown in their districts,” he

explained to our agency.

“Buying voters’ loyalty — not just their cards — becomes

necessary. Most voters offer their cards for sale at varying prices depending

on their neighborhoods.”

He went on to outline how the market functions. “The price

of a voter card in Zayouna differs from that in Al-Fadhiliya, Hay Al-Maamil, or

Hay Al-Amin. Buying a card also requires ensuring that the seller actually

votes on election day — and that’s the hard part.”

To manage that uncertainty, campaigns often pay in stages,

with the last payment made only after the vote. Many also arrange

transportation to polling centers, ensuring that “secured” voters cast their

ballots as promised. “There is always a risk the voter won’t honor the

agreement,” Al-Saadi noted, “and that means a financial loss for the candidate,

especially as prices rise closer to the election.”

However, not every purchase aims to win a vote. Some

political blocs buy cards simply to remove them from circulation, preventing

rival candidates from benefiting. In parts of Baghdad — notably al-Mansour,

Karada, and al-Jadriyah — voters have been offered up to one million dinars

(about $760) to destroy their biometric cards altogether.

Read more: Iraq’s 2025 Elections: Mass candidacy, minimal reform, and crisis of democracy

Biometric Deceit

Beyond these street deals lies a more sophisticated layer of

interference. Speaking on condition of anonymity, an expert familiar with

Iraq’s biometric enrollment system detailed how voter data can be exploited to

falsify identities.

“Powerful individuals linked to certain candidates often

collect voter identification cards to extract personal information — names,

numbers, and other data printed on the cards.” These details are then entered

into the registration system during the enrollment phase, where they are paired

with fingerprints that do not belong to the real cardholders — sometimes from

another person, or even a fabricated print.

When biometric verification is required on election day, the

system matches that false fingerprint, allowing someone else to vote in place

of the legitimate voter. This manipulation, he clarified, may involve temporary

or permanent collection of voter cards, or even collusion with registration

center staff.

If the biometric system, he pointed, lacks features such as

liveness detection — technology that ensures the fingerprint comes from a

living person — or strong audit logs, fraud becomes easier to commit and harder

to trace.

These vulnerabilities have had real consequences before.

During the 2018 parliamentary elections, independent monitors such as the

European Union Election Observation Mission (EU EOM) identified irregularities

in over 80 percent of polling stations, prompting the Independent High

Electoral Commission (IHEC) to annul results at 1,021 polling centers.

In 2021, despite new technology, thousands of complaints

emerged over vote buying, intimidation, and manipulation. The Commission later

maintained that “no proof of systematic fraud” was found — yet the sheer number

of complaints deepened public mistrust.

Read more: The uncivil war: Iraq’s election frenzy

Securing the Vote

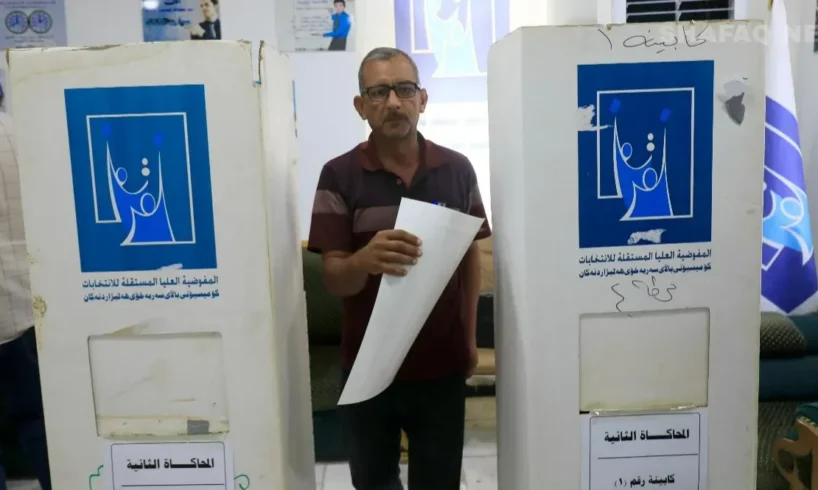

Even so, IHEC insists it is closing those loopholes. Ahead

of the upcoming elections, the commission has introduced new measures to

strengthen transparency and restore confidence in the process.

Among the reforms: the elimination of indelible ink, full

reliance on biometric voter cards, and electronic verification systems. For

voters whose fingerprints are unreadable — about 5 percent of participants —

polling stations will use facial-recognition cameras instead.

Civil society observers and monitoring teams will also be

stationed at polling centers to track instances of vote buying, intimidation,

and card trading.

The reforms follow mounting public pressure for cleaner

elections after the 2021 vote, which saw a historically low turnout. This year,

nearly 7,900 candidates are running for parliament. Out of roughly 30 million

eligible Iraqis, about 21.4 million have completed voter registration, while

another seven million will not participate because they have not renewed their biometric

cards.

Impossible Fraud?

Despite the criticism, election officials insist that

impersonation and voter card misuse are virtually impossible. “It is nearly

impossible to use someone else’s voter card. Doing so is illegal,” affirmed

Nebras Abu Soudah, deputy spokesperson for IHEC.

She also explained that the system requires triple biometric

verification — the live fingerprint, the fingerprint on the card, and the

fingerprint stored in the verification device. “All three must match, and this

cannot happen without the voter present.”

Her colleague, Jumana al-Ghalay, confirmed that Iraq’s

Election Law No. 12 of 2018 provides for prison terms of no less than one year

for anyone who offers or promises benefits to influence a voter’s choice or

prevent participation. “The law also applies to those who use threats or

force,” she noted.

Al-Ghalay further mentioned that no official complaints have

been recorded so far, emphasizing that the voting system is “fully protected,

relying on encrypted codes that prevent any party, including the commission

itself, from identifying voters’ choices.”

Read more: Money, power, and ballots: Iraq’s struggle against electoral fraud

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.