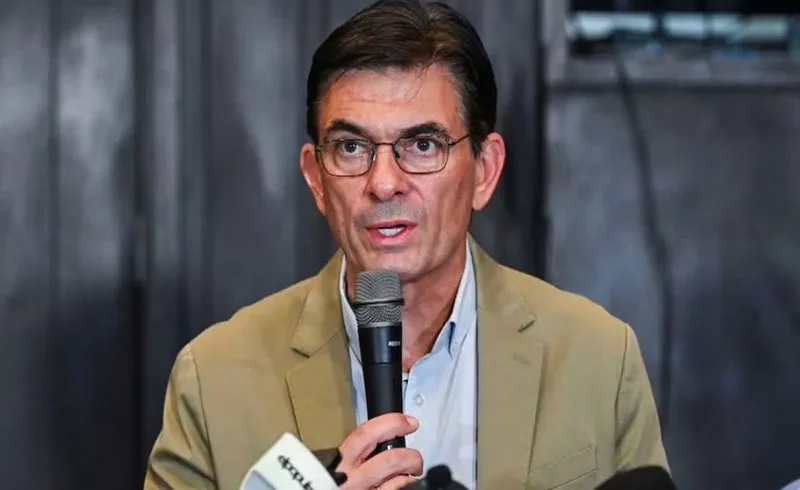

(Analysis) When Rodrigo Paz Pereira went on television in La Paz this week to announce that “the Ministry of Justice has died”, he was not just cutting one ministry to save money.

He was trying to bury an institution he calls “the ministry of persecution” – a symbol of how Bolivia’s justice system has been used as a political weapon for nearly two decades.

Paz, who ended almost 20 years of rule by the left-wing Movement for Socialism (MAS) in elections this month, scrapped the Ministry of Justice a day after firing his own minister, Freddy Vidovic, when it emerged that Vidovic had a past three-year prison sentence for corruption-related offences.

The president then named prominent lawyer Jorge García as a stop-gap minister – only to announce hours later that the whole ministry would be abolished and its functions redistributed.

In his speech, Paz said the ministry had become a place “to sell verdicts” and “blackmail society from political power”.

Venezuelan gas deal offers shortcut but risks remain. (Photo Internet reproduction)

He framed the closure as a campaign promise finally honoured, and as the first step toward a deeper judicial overhaul already being discussed in national “justice summits” with judges, lawyers and civil-society groups.

To understand why this resonates, you have to look back. Human rights organisations have long described Bolivia’s justice system as heavily politicised and widely mistrusted, regardless of who is in power.

Reports under Evo Morales and his MAS successors highlighted excessive pre-trial detention, weak judicial independence and selective prosecutions against opposition figures.

Bolivia’s justice system caught in political swings

The interim government of Jeanine Áñez, which replaced Morales in 2019 and presented itself as a break with MAS, did not reverse that pattern.

Instead, it opened more than 100 criminal investigations against Morales allies and protesters for sedition or terrorism; human rights monitors said prosecutors and judges were publicly pressured to act in the government’s political interest.

When MAS returned to power under Luis Arce, the pendulum swung the other way. Áñez herself was arrested in 2021 and sentenced to 10 years in prison for decisions taken during the 2019 crisis, in a process criticised by international organisations and foreign governments for due-process flaws and apparent political bias.

Bolivia’s Supreme Court has now annulled part of that case, citing violations of her rights and ordering a special impeachment-style procedure.

Other opponents were also caught in the gears. Luis Fernando Camacho, conservative governor of Santa Cruz and a key MAS critic, spent almost three years in pre-trial detention on “terrorism” charges related to the 2019 unrest.

Rights groups and a UN working group denounced his detention as arbitrary and politically motivated before courts finally moved him to house arrest this August.

Seen from this perspective, Paz’s decision is not just an anti-left gesture. It is an attempt – still very uncertain – to break a cycle in which both left and right governments turned a weak justice system into a tool for settling political scores.

Supporters in regions like Santa Cruz have celebrated the closure as the end of a “ministry of persecution”, while the national human-rights ombudsman warns that vulnerable people could lose access to key legal services if the transition is chaotic.

For outsiders, this matters because Bolivia is a test case for a wider regional problem: what happens when courts lose public trust.

If Paz’s reforms produce a more independent judiciary, they could stabilise a polarised democracy and improve the climate for investment and basic rights. If they simply replace one form of political control with another, the “ministry of injustice” will have been buried in name only.

Based on Spanish- and English-language news coverage, official statements and reports by human-rights organisations, I have not invented any events, figures or legal cases in this account.

Where motives or political interpretations are mentioned, they are clearly presented as the views of the actors or of those organisations, not as undisputed fact.