Thanksgiving has been part of American Jewish life almost since the country’s founding. When George Washington proclaimed the first national Thanksgiving in 1789, New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel — the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States — marked the day with special prayers and a sermon by its cantor, Gershom Mendes Seixas, celebrating the new republic and its promise of religious liberty. From the start, Jews understood Thanksgiving as a chance to express gratitude as Jews and as Americans at once.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a wave of Jewish immigrants came to the U.S. from Eastern and Central Europe. Between roughly 1880 and 1924, more than two million Jews arrived from the Russian Empire, Romania, and Austria-Hungary, fleeing pogroms and economic hardship. In crowded tenements and new American cities, Thanksgiving stood out as a rare national ritual that wasn’t tied to Christianity and didn’t threaten Jewish dietary laws (kashrut) or Shabbat.

NEW GIRL: Schmidt (Max Greenfield, L) invites his cousin Big Schmidt (guest star Rod Riggle, R) to Thanksgiving dinner. (Courtesy: Ray Mickshaw/FOX)

Historians of American Jewish life have noted that Jewish immigrants embraced Thanksgiving specifically because it was civic and broadly nonsectarian — a holiday that welcomed them into American life rather than asking them to assimilate away from their traditions.

Today, nearly all American Jews — except for some ultra-Orthodox sects — celebrate Thanksgiving as a time to be with family and give back to the community.

Read more: Is Thanksgiving a Jewish holiday?

A week of gratitude and generosity

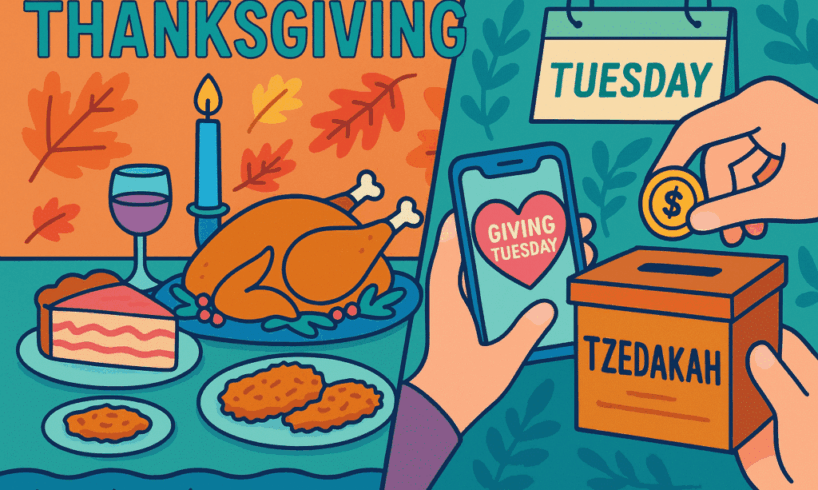

Thanksgiving and Giving Tuesday — the global day of charitable giving that follows the Black Friday/Cyber Monday rush — are less than a week apart from each other. For Jews, this week naturally connects to long-standing values of gratitude, generosity, and compassion for others. One day is about gathering, giving thanks, and hospitality; the next is about philanthropy, community support, and choosing to show up for others. Seen together, this week becomes an opportunity to do good: we name what we’re grateful for, and then we ask what we’re going to do with that gratitude.

For many Jewish families, this pairing isn’t just convenient, it’s deeply resonant. Thanksgiving has long been a holiday that Jews “make their own,” blending traditional American rituals with Jewish food, blessings, and values.

Thanksgiving dinner (Pexels/Karolina Grabowska)

The Thanksgiving table becomes a space to practice hakarat hatov (recognizing the good) and hakhnasat orchim (welcoming guests). Thanksgiving becomes not just an American meal, but a Jewish moment of gratitude and connection.

It’s also worth noting that major rabbinic authorities generally permit Thanksgiving for this very reason: because it is treated as a secular civic holiday, not a religious one. Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik and Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, two central leaders of Modern Orthodox American Jewry in the 20th century, ruled that it was permitted for Jews to mark Thanksgiving since it is not a religious holiday (Although Rabbi Feinstein noted that Jews should be careful not to turn Thanksgiving into an annual celebration that’s too similar to a festival). In practice, most Jews who observe it do so as a family gathering to express gratitude rather than as a religious festival.

However, many Jews — particularly those who are Conservative, Reconstructionist, or Reform — utilize special readings and prayers for integrating Judaism into Thanksgiving meals to bring Jewish spirituality and values to their family gathering. Some denominations even have Thanksgiving mentioned and highlighted in their siddurim (prayer books)

Gratitude as a Jewish practice

At the heart of Jewish life, the practice of hakarat hatov — recognizing the good — is more than simply saying “thank you”; it’s a way of seeing the world. Judaism teaches that gratitude begins with awareness: noticing blessings big and small, acknowledging the people who sustain us, and understanding that our lives are enriched by gifts we did not create alone. This mindset is implemented as a daily practice — from waking up with “Modeh Ani,” a Jewish morning prayer of thanks for the gift of a new day, to the blessings we say over food, nature, study, and even experiences. Thanksgiving, at its core, is a day dedicated to pausing to acknowledge blessings.

There’s even a Jewish seasonal echo here. Sukkot — the Torah’s harvest festival, sometimes called Chag HaAsif, the Festival of Ingathering — is itself a built-in time to thank God for abundance and to practice hospitality. In that sense, Thanksgiving doesn’t feel foreign to Jewish time.

Orthodox Jewish holiday in Sukkah an etrog on Sukkot

The Pilgrims’ harvest festival likely pulled from Sukkot when figuring out how to honor gratitude. The Pilgrims were traditionalist Christians who were knowledgeable of the Old Testament, the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible). When they finally neared the U.S. after months at sea, the first thing they did was recite Psalm 100, which begins, “A Psalm of thanksgiving…” and Psalm 107, which begins, “Praise the Lord, for He is good…”

William Bradford, the leader of the Pilgrims in Plymouth, was knowledgeable in Hebrew. His history of the dissident group starts with a Hebrew-English dictionary. When he led the Pilgrims in Psalms 100 and 107, the Bible he used even included a note detailing how the Jews would say Psalm 107 when they were saved from trouble and wanted to give praise.

Sukkot isn’t the only harvest festival that may have influenced the character of Thanksgiving, though. Sarah Josepha Hale, a poet who made it her mission from 1846 to 1863 to convince Americans to celebrate Thanksgiving as a national holiday, compared Thanksgiving to another Jewish harvest festival: Shavuot (which she referred to as Pentecost).

“The noble annual feast day of our Thanksgiving resembles, in some respects, the Feast of Pentecost, which was, in fact, the yearly season of Thanksgiving with the Jews,” Hale wrote in her appeals to the public. “All sects and creeds who take the Bible as their rule of faith and morals could unite in such a festival. The Jews, also, who find the direct command for a feast at the ingathering of harvest, would gladly join in this Thanksgiving.”

On Shavuot, Jews used to bring a special offering called Bikkurim – the first fruits of their harvest – to the Temple in Jerusalem as thanks to God for the harvest. The holiday is referred to as Chag Ha’Katzir (the Festival of Reaping) and Yom HaBikkurim (the Day of First-Fruits).

Making Thanksgiving “Jewish” at the table

In many Jewish households, it’s common to see brisket, kugel, matzah ball soup, or tzimmes alongside classics like turkey, stuffing, and green bean casserole (which was invented by a Jewish food writer). To adapt to American life while maintaining Jewish customs, many traditional recipes were modified to follow kashrut and incorporate familiar flavors. Some of the most well-known examples are challah stuffing, pareve pumpkin pie, and sweet potato latkes.

Jewish adaptation of Thanksgiving looks different across communities. Sephardi and Mizrahi families might serve a turkey seasoned with za’atar, baharat, or ras el hanout; pumpkin or sweet potato dishes might incorporate tahini and pomegranate; or rice or couscous sides that sit as naturally beside cranberry sauce as any Ashkenazi kugel.

Thanksgiving dinner (Unsplash/Jed Owen)

Beyond food, many Jewish households add blessings, reflections, and moments of gratitude based on Jewish thought.

Rabbi Elizabeth Hersh reflected on biblical and rabbinic traditions, noting that sacrifices of thanksgiving (korban todah) in the Torah were a way to publicly acknowledge God’s goodness, and that we continue this legacy today through blessings and by inviting others to share in our gratitude.

The korban todah was designed to push gratitude outward: it came with 40 loaves of bread and had to be eaten within a single day and night — so much food so quickly that the giver was essentially forced to invite others to join.

Hospitality as a Thanksgiving value

Hospitality (hakhnasat orchim) and communal service are other ways to make Thanksgiving “more Jewish.” Rooted in the story of Abraham and Sarah inviting strangers into their tent, it is considered one of the highest expressions of kindness. Whether it’s inviting someone who has nowhere else to go, making space at the table for a new face, or ensuring that every guest feels honored, hakhnasat orchim turns a meal into a moment of community. It transforms a holiday gathering into an act of connection — a way of saying, “You belong here.”

Some families make this literal by setting aside an open seat for someone new — an international student, a neighbor who’s alone, or a friend who can’t travel home. Others put a tzedakah box on the table and invite guests to drop in a few dollars for charity before dessert, turning thanks into action.

A Tzedakah box (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)

Synagogues, Jewish organizations, and interfaith groups often organize volunteer meals, food drives, or joint service projects around Thanksgiving, framing the holiday as a celebration and an obligation to help others. In this way, gratitude becomes a spiritual discipline. It shapes how we relate to the world and to each other, reminding us that recognizing the good is the first step toward spreading it.

Many Jews also hold Thanksgiving with moral awareness that the national story around the “First Thanksgiving” is complicated for Indigenous communities, who often see the day as tied to colonization and loss. That tension can deepen, rather than diminish, the Jewish call to gratitude joined with justice, and is often seen as a time to acknowledge the links between the Jewish and Native American communities.

Giving Tuesday and tzedakah

In Judaism, tzedakah is not framed as optional but as an obligation rooted in justice. The word itself is derived from the Hebrew word for justice, tzedek.

Maimonides – one of the foremost of Jewish law and philosophy in the Middle Ages – wrote clearly that giving to those in need is a positive commandment:

“We are obligated to be careful with the mitzvah of tzedakah more than all other positive commandments.” — Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Matanot Aniyim 10:1

Maimonides’ famous hierarchy places sustainable, dignity-centered giving at the top:

“The greatest level, above which there is no greater, is to support someone by giving a gift or loan or entering into a partnership with the person… to strengthen his hand until he needs no longer be dependent on others.” — Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Matanot Aniyim 10:7

This concept mirrors how contemporary Giving Tuesday campaigns emphasize long-term impact, empowerment, education, and stability — not just emergency responses. The Jewish spirit of Giving Tuesday is to give not because it feels good, but because it is right.

Tzedakah box or Kupat Tzedakah, Charleston, 1820, silver, National Museum of American Jewish History (Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

Long before Giving Tuesday existed, Jewish communities built systems to make sure giving wasn’t left to impulse. Maimonides describes the kupah (a communal charity fund) as a fixture of every Jewish community, and tamchui funds helped provide regular food relief. It is customary to give extra tzedakah before Shabbat and holidays so that every person can celebrate with honor and joy. As a result, many Jewish communities do their own version of Giving Tuesday before the Thanksgiving holiday.

On the individual level, many Jews practice ma’aser kesafim (tithing) — the custom of setting aside roughly 10 percent of one’s income for tzedakah — turning generosity into a steady discipline instead of a once-a-year gesture.

Giving Tuesday was introduced in 2012 after the consumer rush of Black Friday and Cyber Monday, with a simple idea of giving back. Today, it is a global movement encouraging others to donate, volunteer, and support the organizations that strengthen their communities.

This shift — from feeling thankful to actively giving — resonates deeply with Jewish thought. In Judaism, gratitude isn’t meant to stay internal; it naturally flows into tzedakah (righteous giving) and gemilut chasadim (acts of loving-kindness). We are taught that recognizing our blessings is only the first step. The next step is using those blessings to uplift others.

Tzedakah in Judaism isn’t “charity” — it’s justice. It’s an obligation to redistribute resources and care for others. Giving Tuesday takes that idea and channels it into one big global invitation to give, fitting perfectly with the ancient Jewish concept of giving as a responsibility, not an optional gesture.

Together, Thanksgiving and Giving Tuesday form a natural arc: hakarat hatov (recognizing the good) leads to tikkun olam (repairing the world). We acknowledge what we have — and then we make sure others can experience that goodness too.

We express gratitude, and then we act on it. We remember the blessings in our lives, and then we help extend those blessings to others. It’s a rhythm that feels distinctly Jewish, a reminder that joy is most meaningful when it leads to generosity, and that gratitude is most powerful when it inspires communal care.