This is the third of a four-part series. Parts one and two are available here.

Trotskyism and the Struggle Against Pabloism

The betrayals that shaped Tanzania’s postcolonial trajectory cannot be understood outside the international struggle waged by the Trotskyist movement against Pabloism, a revisionist and opportunist current that emerged within the Fourth International led by Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel.

The revolutionary upsurge that followed the catastrophe of the Second World War shook both Europe and the colonial world. In Europe, large sections of the bourgeoisie, discredited by their collaboration with fascism, would have been unable to reestablish their power and stabilise capitalism without the decisive political intervention of the Stalinist bureaucracy and the economic might of US imperialism.

Moscow instructed the Communist parties in France, Italy, and Germany to support bourgeois governments, disarm the resistance fighters, and suppress any independent initiative of the working class. In Greece, Stalinism ensured the victory of the bourgeoisie in the civil war by withholding vital support from the workers and partisans who had fought the Nazi occupation. These betrayals saved European capitalism from collapse and allowed it to reassert its grip on its colonies.

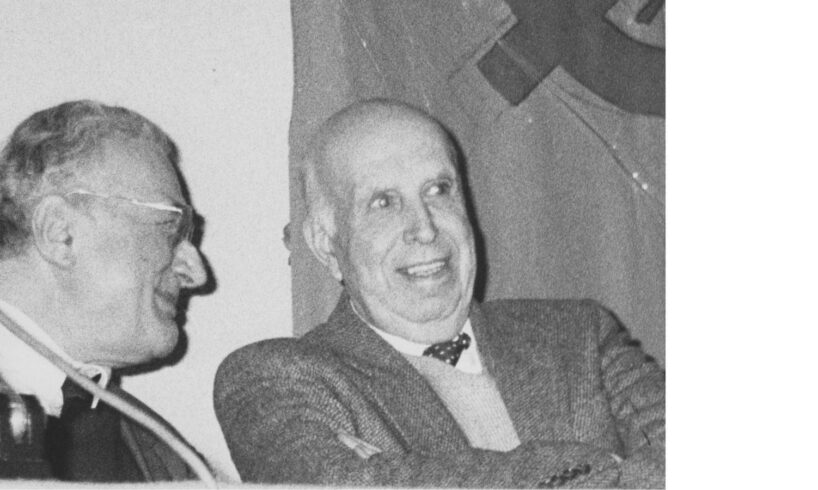

Michel Pablo (right) with Ernest Mandel

It was in this context that Pabloism arose within the Fourth International. Confronted with the temporary stabilisation of capitalism and the creation of deformed workers’ states in Eastern Europe, Pablo abandoned Trotsky’s insistence on building independent revolutionary parties of the working class. He called for dissolving Trotskyist organisations into the “mass movements” led by Stalinist, nationalist, or petty-bourgeois forces. Any attempt to characterise such movements by their class nature, he insisted, reflected “old-type Trotskyist immaturity.” Trotskyists must integrate themselves “unconditionally” into national-liberation movements even when these were bourgeois in leadership.

The International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI) was founded in 1953 in opposition to this revisionism. Led by James P. Cannon of the American Socialist Workers Party, Gerry Healy of the British Socialist Labour League, and Pierre Lambert of the French Internationalist Communist Party, the ICFI defended the programme of Permanent Revolution and the need to construct independent Trotskyist parties.

The consequences of Pabloism were disastrous. On the eve of the 1953 split the Fourth International had 22 official sections and sympathising groups in dozens of countries. Pabloism liquidated these cadres into Stalinist parties and bourgeois-nationalist movements and left the working class politically disarmed at the very moment when the anti-colonial revolutions were reaching their peak.

Pablo spelled out his perspective in his 1959 article “The African Revolution: Toward the Independence and Unity of Negro Africa”, written under the pseudonym Jean-Paul Martin. Africa, he argued, was passing through a “bourgeois-democratic phase” led by figures such as Nkrumah, Sekou Touré, Senghor, and Nyerere. This leadership, he insisted, sought “only the creation of the bases for capitalist development under African control” after independence. Adding, “The irresistible movement towards African independence and unification is in the hands, for the time being, of leaders and parties ideologically, if not socially, bourgeois in character. This is inevitable in the first phase of the developing African revolution.”

Trotskyists, he insisted, must work inside these nationalist movements, “While giving critical support to the bourgeois African organizations to the extent that they lead an effective struggle against imperialism, and for independence and unification, Marxist cadres have the duty of preparing the formation of autonomous working-class parties.” In other words, the assumption rested on the objectivist line that history itself would push the nationalist leadership to the left.

The following year, as Nigeria, the Congo, Senegal, Mali, and Somaliland approached formal independence, the Pabloites asserted that the “extreme left wings” of nationalist movements and sectors of the trade-union leadership would naturally evolve into socialist forces and “play a more and more important role in the young African states and will stake its claim to lead the African nation”.[1] Nowhere was there a call for constructing Trotskyist parties.

In Tanzania, the Pabloites shifted their appraisal of Nyerere. In 1963 they declared that his African Socialism “takes the incidentals of socialism and ignores the methods of the workers states, and ignores its essentials, the expropriation of capitalism.” Yet only four years later they were hailing Nyerere’s limited nationalisations, claiming that “it is unquestionably a step along the Zanzibari road, the road of socialism, since it pronounces itself in favour of control over the nationalised means of production by the worker and peasant masses.”[2]

Similarly across Africa, the Pabloite line produced a series of political catastrophes. In Algeria, Pablo proclaimed the National Liberation Front (FLN) struggle against French imperialism as the “living permanent revolution,” dissolving the distinction between a bourgeois-nationalist movement and a socialist revolution. He served as an adviser to the FLN government until the 1965 coup that overthrew Ahmed Ben Bella forced him to flee.

In South Africa, the Pabloites hailed the Stalinist Communist Party of South Africa, which was fully integrated into the bourgeois-nationalist ANC, as having turned “squarely to the Revolution.” In Kenya, they urged subordination to the “left wing” of Kenyatta’s Kenya African Naional Union (KANU).[3] In Angola, the Pabloites supported various petty-bourgeois guerrilla movements, including the Soviet-backed People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and even the CIA-backed National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), calling on Marxists to help them “find their way to the programme of socialism”.[4] They hailed the new regime in Zanzibar as “an outpost of social revolution,” ignoring the bourgeois-nationalist character of its leadership.[5]

Third Congress of the ICFI (1966): Back: M. Banda, C. Slaughter Front: P. Lambert, G. Healy, M. Rastos, S. Just

The ICFI warned of the consequences. In May 1961, seven months before Tanganyika’s independence, the British Socialist Labour League (SLL) analysed the role of the national bourgeoisie with a warning:

An essential of revolutionary Marxism in this epoch is the theory that the national bourgeoisie in under-developed countries is incapable of defeating imperialism and establishing an independent national state. This class has ties with imperialism and it is of course incapable of an independent capitalist development, for it is part of the capitalist world market and cannot compete with the products of the advanced countries…

While recognising that leaders like Nyerere, Nkrumah, Mboya, Nasser, or Nehru could strike harder bargains with imperialism, Trotskyists insisted that they acted as buffers between imperialism and the mass of workers and peasants. “The dominant imperialist policy-makers both in the USA and Britain recognize full well that only by handing over political ‘independence’ to leaders of this kind […] can the stakes of international capital and the strategic alliances be preserved in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.”

For Marxists, the decisive question remained the political independence of the working class, secured through the building of a revolutionary socialist party. The SLL concluded:

It is not the job of Trotskyists to boost the role of such nationalist leaders. They can command the support of the masses only because of the betrayal of leadership by Social-Democracy and particularly Stalinism, and in this way they become buffers between imperialism and the mass of workers and peasants. The possibility of economic aid from the Soviet Union often enables them to strike a harder bargain with the imperialists, even enables more radical elements among the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois leaders to attack imperialist holdings and gain further support from the masses. But, for us, in every case the vital question is one of the working class in these countries gaining political independence through a Marxist party, leading the poor peasantry to the building of Soviets, and recognizing the necessary connections with the international socialist revolution.”[6]

In 1964, three years after Tanganyika’s independence, the SLL assessed Nyerere’s regime. “Leaders like Nyerere represent a middle-class section prepared to supervise the continued exploitation of the workers and peasants in return for concessions for themselves. This is known as ‘independence’.” The Newsletter went on to warn that the high hopes invested in the national-liberation leaderships would rapidly collide with reality: “For millions of Africans, independence meant more than the ceremonial raising of a flag and the transfer of posts. The old nationalist leaders are already being challenged, and those who come after them will fare no better unless the working class takes the lead.”

The SLL insisted that no solution could emerge from within the confines of bourgeois nationalism or Stalinism. “Other nationalist groups making more radical demands will only be driving a harder bargain with imperialism, not fighting to smash it.” The only viable perspective lay in “A Marxist leadership, basing itself on the working class”, one that would consciously link the African revolution with the struggles of workers in the imperialist centres.[x]

The elevation of bourgeois nationalism by Pabloism to the role of revolutionary leadership cut off the most militant layers of the anti-colonial movement from the programme of Permanent Revolution. The fragmentation of Africa into more than fifty states along colonial borders was not the “inevitable” outcome of a bourgeois-democratic stage, but the direct product of the counterrevolutionary role of Pabloism.

Today, the ICFI’s defence of Permanent Revolution stands vindicated. Nationalist movements like the MPLA, FRELIMO, the ANC, the FLN, KANU, ZANU-PF, once hailed by the Pabloites, have all demonstrated their bankruptcy. They have either collapsed, been overthrown, or survive as ruling elites presiding over regimes enforcing IMF austerity, privatisation, and the violent suppression of workers and rural masses. Trotsky’s warning that history would “not leave one stone upon another” of the old Stalinist and social-democratic parties now applies equally to the national-liberation movements.

The fight waged by the ICFI remains decisive: the struggle for genuine national liberation and socialism in Tanzania, as in every country, requires the construction of a revolutionary Marxist party rooted in the working class and oriented to world socialist revolution.

To be continued

In depth

History of the Fourth International

The International Committee of the Fourth International is the leadership of the world party of socialist revolution, founded by Leon Trotsky in 1938.