As questions around horse welfare grow, can equestrian sport’s Olympic dream survive?

When the images are uploaded to Instagram they come with a warning, “graphic f***ing content, like it’s f***ed”.

The mangled leg of a horse fills the screen. “Not clickbait, horses [sic] foot falls off, real footage,” the caption reads, along with the hashtag “RIPQuartzR”.

Quartz R is a pregnant mare it’s hoped might birth a talented sports horse — perhaps one capable of performing the complex dressage movements often compared to ballet.

These images are far from the glossy ones of riders in tail coats and top hats astride sleek, precious horses. Dressage is “the ultimate expression of horse training and elegance”, according to the sport’s governing body. “The intense connection between both human and equine athletes is a thing of beauty to behold.”

But here, in a stable near Newcastle on the flood plains of the Hunter River, those lofty ideals appear to have fallen short.

Quartz R was owned by Heath Ryan, a former assistant coach and competitor of Australia’s Olympic equestrian team. From his property near Newcastle, north of Sydney, Ryan has bred countless elite competition horses and trained generations of riders. “Basically, everyone working here wants to be a top of the range rider, Olympian. The dream is important…” his website says.

Yet when it comes to equestrian sports, especially dressage, the Olympic dream is hanging by a thread.

WARNING: This story contains images of an injured horse that may disturb some readers.

Almost everyone, including the sport’s Swiss-based international governing body, the International Equestrian Federation (FEI), agrees its reputation is in crisis. Many fear equestrian events will be struck from the Olympics over concerns for horse welfare. And the culmination of thousands of years of breeding, training and tradition will limp into oblivion.

A series of horse welfare scandals involving top riders has rocked the privileged, quaint world of horseriding in recent years. Ryan is one of the riders currently entangled in a controversy.

The FEI is investigating Ryan “following allegations of horse abuse reported to the FEI and Equestrian Australia, as well as the posting of a video on social media showing abusive training techniques,” it says. No findings have yet been made against Ryan, and the investigation is ongoing.

Now, images and videos of Ryan’s horse Quartz R obtained by the ABC, which were shared on a private Instagram in October 2022, show a serious leg injury raising questions about adequate care to an injured horse.

Allegations have been raised that the pregnant mare was not properly treated in the days after she injured her leg in a paddock fence, according to people with knowledge of the incident.

Those who spoke to the ABC on the condition of anonymity — because they fear they’ll be ostracised for speaking up in the tight-knit equestrian scene — say the leg emitted a terrible, overwhelming smell that seeped through the stable at Ryan’s property where Quartz R was being kept.

They say Quartz R was eventually euthanised after part of her hoof detached. In one video a person can be heard saying “her foot just fell off” as a bandage on Quartz R’s injured leg is unwrapped.

Loading…

Equine veterinarian Dr Ian Fulton, who has no first-hand knowledge of the case but viewed photos and videos for the ABC, says the images show a “very serious and potentially life-threatening” tendon injury.

“That horse was not cared for appropriately based on the state of the leg and the method of bandaging,” says Fulton, a specialist equine surgeon who has also served as the president of Equine Veterinarians Australia. He also says a splint evident in one of the images is “not an appropriate splint for that injury”.

Fulton says this type of injury requires detailed veterinary assessment and treatment.

Ryan did not respond to detailed questions by the ABC about what care was provided to Quartz R and what processes were in place for managing injuries.

The FEI’s investigation into Ryan was sparked when a grainy video of a separate incident was shared online in June. It appeared to show him repeatedly whip a horse.

After the video was published online, Ryan said in a statement on Facebook: “If I had been thinking of myself, I would have immediately just gotten off and sent Nico [the horse] to the knackery.” He described the video as “awful” and said he was trying to prevent the horse from being sent to the slaughterhouse by seeing if it was “salvageable” for riding.

“All of this transpired sincerely with the horse’s best interests the sole consideration. Unbelievably, it was so successful for everyone except me with the release of this video,” he said.

His response led some to ask, if Ryan had the horse’s interest at heart, why was he whipping him? Equine behaviour experts Anne Quain and Cathrynne Henshall wrote in The Conversation: “Ryan’s justification points to a culture where horses’ needs and interests are not respected and where they are valued solely for their utility to humans.”

Within 24 hours of the video appearing online, Equestrian Australia (EA) announced it was investigating the incident. Yet the ABC has revealed EA first received a link to the whipping video and a formal complaint about Ryan five weeks earlier. EA told the ABC: “While it recognised this particular complaint was not escalated in a timely manner, the EA leadership team acted swiftly as soon as it became aware of the incident”, which it says was the same day the video became public.

But the ABC understands that the existence of the complaint was raised with a member of the EA leadership team more than a week before the video was made public.

What can happen to horses behind the scenes is not the only question bubbling to the surface. What’s occurring in the public eye at equestrian events is also being labelled by some experts as concerning.

Ahead of the 2024 Olympics the FEI launched a marketing campaign to celebrate “the essential connection between horse and human”. The following month, three-time Olympic dressage gold medallist Charlotte Dujardin (the “golden girl of British equestrian” ) was suspended after she was caught repeatedly whipping a horse during a training session.

In response, the animal rights group PETA called on the IOC to remove equestrian events from the Olympics. And celebrated German Olympian Isabell Werth told Reuters “we need to establish a culture of respecting the horse as a creature… otherwise, we’ll have a hard time making our case to the rest of the world”.

That Werth said this while competing on a horse acquired from the stables of a Danish Olympic equestrian who was suspended over animal abuse at his training facility was not lost on some reporters. (There’s no suggestion that Werth’s horse was one of the horses harmed.)

Just how compatible equestrian competition is with “respecting the horse” is being called into question.

A horse welfare crisis

“A lot of distress happened in here,” Dr Andrew McLean remarks, standing in a stable pockmarked with holes, dents and bite marks left by isolated and anxious horses.

McLean keeps horses on his property south-east of Melbourne. The stable, used years ago by owners who bred racehorses, is empty: a memorial to the ruthless, unflinching attachment to the way things have always been, where horses are expendable objects at the whim of humans.

A scientist and equestrian, McLean, 70, has spent decades working methodically from the inside to bring about a change of consciousness in horse sports.

McLean volunteers his time as a member of the FEI’s six-person Equine Welfare Advisory Group. He believes the current horse welfare crisis in equestrian sport comes down to two things: money and training.

He says some people punish horses for what they see as poor temperament or misbehaviour, but a so-called “naughty horse” is simply poorly trained or traumatised. From being weaned from its mother too early, isolated from other horses and starved of physical touch, (“the glue that holds social species together”), kept in stables and denied natural behaviours like grazing, or trained in a confusing or coercive way.

As one horseriding instructor told the ABC: “There are no stupid horses only stupid riders.”

Money has poured into equestrian sport since the end of WWII and “people are racing to get gold medals because people’s lives are built around them,” McLean says. This equine arms race has led to extreme breeding programs and harsh training techniques, he argues.

Society is changing too. Attitudes to how animals are treated are evolving. Horse racing faces increased scrutiny and horses have already been withdrawn from the modern pentathlon after a German coach was filmed punching a horse who wouldn’t jump at the Tokyo Olympics. The incident was reportedly not the only reason the pentathlon was changed — critics say it’s antiquated and unpopular — but is believed to have been the catalyst for moving quickly.

“Pit Viper is a fairly horrific name for a very nice horse,” McLean says, introducing the ex-racehorse he is training for eventing — the equestrian event combining the three disciplines of dressage, show jumping and cross country.

McLean says the allure of horses is hard to explain to the uninitiated. “There’s something that’s intangible about the relationship,” the third-generation equestrian says. “Often, I forget about it and as soon as I bring the horse in, I remember the feeling again, it’s just such a great feeling.”

A desire for a competitive edge in eventing led him to research how horses learn. Along with veterinarian professor Paul McGreevy, McLean developed equitation science — described as “the science behind the art of horse training, riding and the understanding of equine learning processes”.

Horses have sensitive skin, with similar pain receptors to humans, McLean says: “So, it’s easy to teach them through the application of pressure, and then the release of that pressure, to do things, and that’s how horses learn to stop and go and turn.”

Horses’ sensitivity has made them easy to use, for about the last 5,000 years, for transport, agriculture, war and more recently leisure and sport, McLean says. “So, the horse’s natural tendencies lend themselves to be trained by humans, but that’s the problem because that’s where we sit now in this difficult era.”

Horses experience pain, fear and pleasure

“Social license to operate” is a term which originated in the mining industry and has come to describe the public’s acceptance of horse sports, professor Phil McManus says.

“It’s a very nebulous concept… it’s the notion that something can be legal, but if it loses the popular support, if it loses the willingness of people to accept it… [it’s] at risk,” he says. “It was the justification used in NSW to try to close the greyhound industry,” he says.

McManus, a professor of human geography at the University of Sydney, says the realisation animals are sentient beings has changed the perception of horse sports.

Science has found humans are not the only animals capable of experiencing positive and negative feelings like pain, fear and pleasure. Yet the obligation people feel they owe animals in horse sports varies.

“The idea of animals being used in any form of human entertainment, and particularly where there’s profit to be made so they’re more of a commodity … is not accepted [by some],” McManus says. Others justify using horses in sport if the horse is cared for and its welfare is considered, and at the other extreme is the idea that “it’s just a horse,” he adds.

‘Year of the blue tongues’

Jumping was Cristina Wilkins’s favourite discipline. “I loved the feeling of being in perfect balance with my horse,” she says. “But good riding is an anthropocentric pursuit. Horses don’t choose to take part in competitions,” she adds.

Over decades as an elite rider, coach and equestrian journalist, her relationship with horses has evolved. Now she’s undertaking a PhD investigating how humans interact with horses at the University of New England.

She calls 2024 “the year of the blue tongues”.

At the 2024 Olympics, the FEI’s chief vet Goran Akerstrom told Reuters the FEI had reviewed photographs taken during the dressage competition which showed harm to animals done by equipment that likely restricted oxygen to the tongue and caused “pain or unnecessary discomfort”. Despite the vet’s findings the FEI did not take any disciplinary measure against riders.

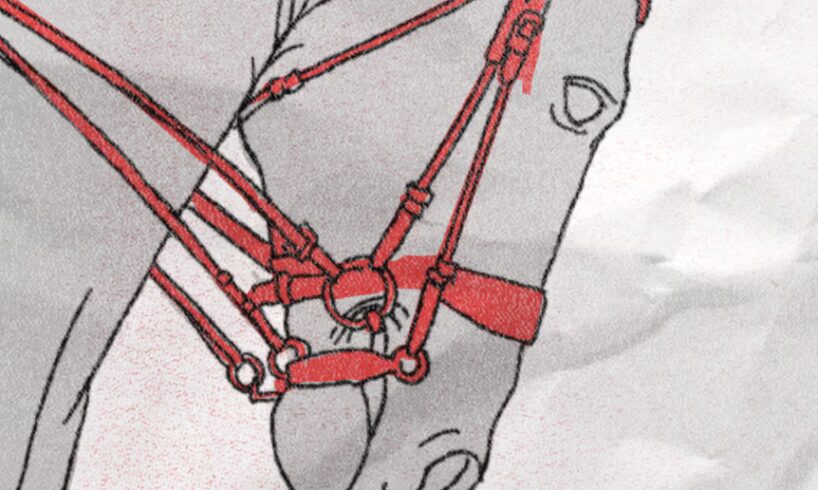

Wilkins is part of an eminent academic team who presented research into horse welfare in dressage to the FEI Veterinary Committee earlier in the year. The team wrote to the FEI to report “potential horse abuse”, saying their analysis of high-definition photographs taken at elite competitions revealed “considerable welfare concerns” related to the use of regulation double bridles.

Wilkins says the photographs, taken by Crispin Parelius Johannessen, show signs of harm and the horses exhibit behavioural indicators of pain and distress.

The FEI says many of the “areas identified” by the researchers are being addressed through its ongoing work to improve horse welfare. However, “following a review of the evidence presented, the FEI decided not to impose any sanctions on the athletes”.

The FEI has established an Equine Welfare Strategy Action Plan and a welfare advisory group in recent years. However the FEI doesn’t publish the group’s recommendations nor is not bound to implement them.

Johannessen’s photographs provoke explosive conversations on equestrian social media pages. Many equestrians say equipment like double bridles are harmless in the hands of experienced riders. Most riders say they love their horses and want the best for them. They don’t believe what they do causes pain or distress.

Focusing on the horses’ heads up close, Johannessen says he’s revealing welfare issues observers don’t always notice when watching dressage. But Johannessen also argues he’s exposing what has been visible all along. “I think art has actually documented quite a lot of violence against the horse, but we just don’t interpret it like that,” he told Epona.tv. “Because we’re interpreting it into a different narrative, one that is preoccupied with status, money, power — horses have always been accessories of human history.”

Di Evans, veterinarian and RSPCA’s senior scientific officer says, “science is linking signs of pain and how horses are being used in competition”. Horses are stoic animals who mask signs of pain and stress, she says. “That’s why when we see what we see this is extreme.” She argues that change is needed: “Recognition and acceptance of the evidence but also acceptance of the responsibility that all involved in equestrian sports need to recognise and apply the science in terms of detecting when horses are in a state of fear, pain or stress, and then taking immediate action to do something.”

In 1998, McLean learnt to ride his stallion Tintagel Magic without a bridle. A thin rope draped around the horse’s sleek, muscular neck was enough to signal to the horse what he wanted it to do. McLean believes communicating pressure/release to a horse without causing it pain is possible. The kind of pressure one might apply to a child’s hand while crossing a road, he says.

There’s a growing movement of what McLean calls “light” riders who are starting to be recognised with wins in competition. He says it’s a step in the right direction.

“We became inured to what we do with horses,” he says. “It’s normal to ride a horse at a high level with a curb bit. It is normal for young kids to learn that … [hyperflexion] gives you better marks,” he says. “It was normal to ride horses with long spurs, it was normal to do the noseband up as tight as you need to, because you would get a good performance, but that of course is the old way of looking at things, of horse as object — like what can the horse do for us for us to win our medals and do the things we want to do.”

He sees rider education as the path to better horse welfare. And he’s forgiving of past behaviour. “As an equestrian competitor, I came up through the same utilitarian school where punishment was used for a horse’s ‘bad behaviour’ and it was normalised and seemed right,” he says.

But his faith in education, that “when we know better, we do better”, isn’t limitless. “If that education system doesn’t work and in years to come the world is no better with horses then we shouldn’t have them. We shouldn’t be doing what we do. There’s no justification. We have a big responsibility to do the right thing with animals.”

These days, his mantra is: “If you tell me that you’ve trained a bird to sit on your arm, you’ve got to let go of his wings because that’s what training is.”

Catch up on our latest Long Reads

The childcare dilemma

The landline is having a moment

How social media algorithms decide who you are

Lawyers already use AI. Will judges be next?

The case against babies

Credits

Words and production: Rhiannon Stevens

Editing: Catherine Taylor

Illustrations: Lindsay Dunbar