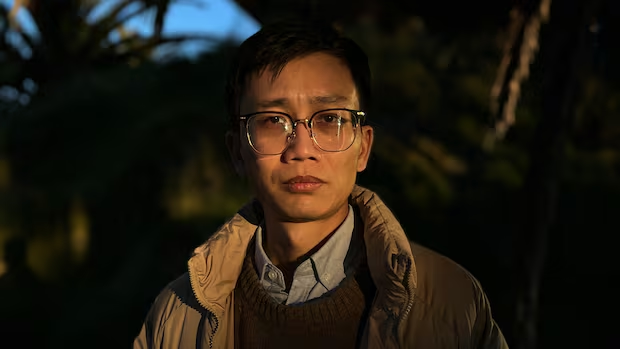

A man who spent a decade and a half working as a Chinese spy has shared details of some of his missions with Radio-Canada, including what he knows about a Chinese dissident who died in B.C. in 2022.

“From 2008 to 2023, my real job was to work for China’s secret police. It’s a means for political repression,” said “Eric,” who was interviewed in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia. “Its main targets are dissidents who criticize the Chinese Communist Party.”

Eric shared a variety of documents — including financial records, secret money transfers and the names of spies — with journalists from the Australian Broadcasting Corp. and the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, of which CBC/Radio-Canada is a partner.

The records give an unprecedented glimpse at the inner workings of China’s overseas spy operations.

Eric was willing to be filmed and photographed but didn’t want Radio-Canada to use his real name. The interpreter hired to translate from Mandarin also asked not to be named, out of fear of reprisal.

Chinese artist Hua Yong staged a protest in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4, 2012, where he punched himself in the nose and then used his blood to write ‘6-4,’ representing the date of the 1989 massacre. Hua died mysteriously in November 2022. (Hua Yong/Twitter)

Eric explained that he was once a pro-democracy activist, having joined the underground Social Democratic Party of China. But he said he was forced into spy work after receiving a visit from the police one day.

For 15 years, Eric worked for the 1st Bureau at China’s Ministry of Public Security, a unit that specializes in surveillance of dissidents abroad. He previously told the Australian Broadcasting Corp. that he spied on a Japanese-based cartoonist and a YouTuber exiled in Australia. Often, he said, his cover was working for real companies in the countries where he was deployed — companies that collaborated with China’s secret police.

CBC/Radio-Canada was able to verify the vast majority of his claims using his phone’s archives.

For example, while on assignment in Cambodia, his cover was with the Prince Group, a multibillion-dollar conglomerate with interests in real estate and financial and consumer services. (The company did not reply to messages from Radio-Canada.)

In 2020, Eric said he was tasked with snooping on a dissident named Hua Yong, an artist and hardcore opponent of China’s Communist Party who eventually ended up on B.C.’s Sunshine Coast.

(The Chinese Embassy in Ottawa did not reply to multiple messages about the details of this story, including an interview request.)

Befriended artist online

After staging a protest in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 2012, Hua was arrested and sent to a re-education labour camp. He was eventually released but arrested again in 2017 for documenting mass evictions in a working-class Beijing neighbourhood.

By March 2020, Hua was in exile in Thailand. Eric said Chinese authorities wanted him captured, but they felt he was out of reach there. So Eric’s handler instructed him to lure Hua to Cambodia or Laos — countries that have close ties with China.

Eric’s assignment was delivered to him via voice message on one of several messaging apps he and his handlers used over the years. It was one of thousands of audio and text exchanges, including his communications with his bosses, that Eric held on to.

Among them are Eric’s handler’s messages to him in Mandarin about Hua:

Listen to my request below. It’s about Hua Yong. The higher-ups find him quite annoying and want to deal with him.- Eric’s handler

(The latter phrase could also be translated as “want to get rid of him.”)

Eric said he talked with his bosses about different ways to entice Hua to go to another country where China’s secret police could get at him. Ultimately, Eric came up with a strategy: He started chatting with Hua on social networks, then moved to encrypted messaging apps. In a conversation on the app Telegram, Eric suggested they set up a resistance group and try to build a following.

Fake rebel army

To gain Hua’s confidence, Eric invented a fake anti-Communist rebel group called the V Brigade and started posting about it on social media.

In a video posted to YouTube in September 2020, Eric is wearing a three-hole balaclava and camo and is seen firing blanks. He announces: “Hello, everyone. I’m here with V Brigade to introduce today’s topic: How to individually prepare for armed revolution and armed struggle.”

The ruse worked.

Chinese ex-spy Eric invented a fake anti-Communist rebel group called the V Brigade to gain Hua’s trust and posted this promotional video for it on YouTube, in which Hua can be seen firing a blank gun. (V Brigade/YouTube)

“This is awesome!” Hua wrote to Eric, as the two became revolutionary comrades and even met up in Bangkok at one point.

But in early April 2021, the Chinese secret police lost track of Hua. A brief scramble ensued. Eric reported to his handlers that Hua appeared to have gone to Turkey and then Paris.

Then on April 6, Hua posted on social media that he was in Canada. He invited Eric to join him and become the spokesperson for a revolutionary group. Eric’s handlers ordered him instead to return to China and keep tabs on his target from afar.

No foul play in death, RCMP said

Hua ended up moving to Gibsons, B.C., where he took up crab fishing and kayaking, his own social media posts show.

In the fall of 2022, Hua was out paddling when his kayak nearly capsized after a luxury yacht passed near him.

“For him, this was a mere accident. But to me, it looked like an orchestrated murder,” said Li Jianfeng, a former judge in China who also served prison time there before being granted refugee status in Canada.

Li said he helped Hua escape to Canada.

Hua fled to Canada in April 2021 and later moved to B.C. and took up kayaking. He died while kayaking not long after this photo was taken, in November 2022. (Hua Yong/YouTube)

A couple of weeks later, on Nov. 25, 2022, Hua went out for another paddle, but this time he didn’t come back. After a night of searching, his body was found along the shore of an island off the Sunshine Coast.

The RCMP saw no foul play at the time. But the force didn’t appear to know then that Hua was in the crosshairs of a covert operation by China’s secret police.

“I fully understand the modus operandi of the Chinese Communist Party,” Li told Radio-Canada in an interview, referring to his former job in China’s justice system. “They would stage an accident to murder someone. Yes, I don’t have direct evidence to prove his murder.”

Li said he put together a dossier with several different leads and sent it to the RCMP.

Li Jianfeng, a former judge in China who himself was imprisoned for ‘subversion,’ holds a plaque he made commemorating Hua. (Radio-Canada)

Guy Saint-Jacques, Canada’s former ambassador to China, said no possibility should be excluded. “China’s regime has no shame and doesn’t hesitate to use brutal means to attain its objectives.”

Eric told Radio-Canada he suspects other informants were keeping an eye on Hua in Canada.

“Based on the Chinese police’s commonly known operating methods, the party definitely has other agents in Canada, including spies or other special operation teams,” he said. “I’m almost certain of this.”

Spy flees

After several failed attempts to flee China, Eric finally succeeded in 2023. The former spy wanted to go to Canada to claim asylum but ended up in Australia because he was able to get a tourist visa there.

The world has a right to know what China’s secret police are up to, Eric said, adding that revealing it publicly actually buys him a measure of protection.

Meanwhile, the police investigation into Hua’s death isn’t officially closed because three years later, the B.C. Coroners Service still hasn’t completed its report, which normally takes about 16 months.

Eric said he’s had no contact with Canadian police but that he did confidentially send some documents to the Hogue commission, Canada’s public inquiry into foreign interference.

“There are some strange aspects to this case that demand further investigation,” he said.