Shafaq News

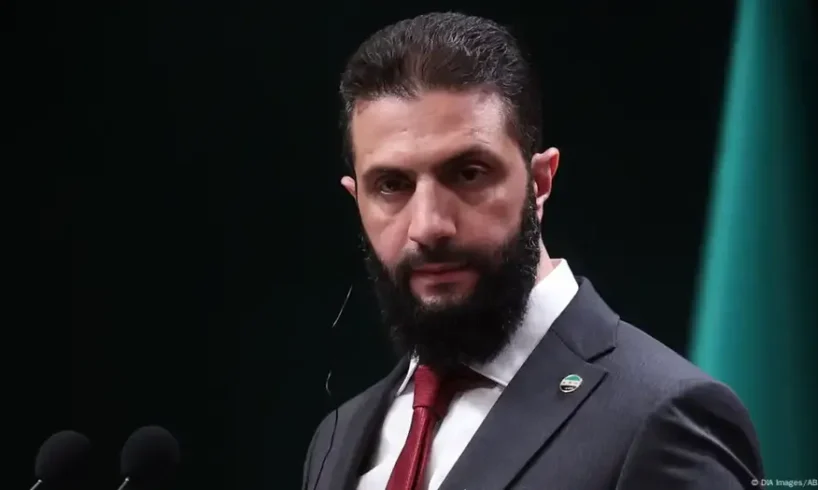

One year after the fall of Bashar Al-Assad and the rise of

Ahmad Al-Sharaa, Syria looks less like a country emerging from a long war and

more like a state entering an even more complex test. The front lines may have

quieted, but the political, social, and territorial fractures remain wide open.

At the heart of this new phase lies a concern: whether

Damascus can translate its external reintegration into a credible internal

settlement—one that reassures minorities, manages the peripheries, and rebuilds

the state—before those same peripheries move toward forms of autonomy or

fragmentation. Today, Syria is pulled simultaneously between breaking its

external isolation and restoring ties with the world, reconstructing a

suspended social contract at home, and containing restive regions stretching

from the Kurdish northeast to the Druze south, all while confronting Israeli

military encroachments. How these tracks converge or collide will shape the

country far more than the battlefield did.

If the Al-Sharaa government has achieved one clear success

this year, it is Syria’s partial return to international maps. Western and Arab

capitals have reopened channels, and Washington now holds the key to the most

consequential file: sanctions relief and access to global finance. While

Damascus speaks of “quiet but advanced” discussions with the United States,

Washington insists that any easing of sanctions must be tied to political space

at home, protection of minorities, border control with Iraq and Jordan, and the

curbing of non-state armed groups.

Humanitarian assistance has increased modestly, and small

rehabilitation projects have begun in northeastern Syria and parts of Damascus,

but the Syrian government still awaits a structural change in

sanctions—especially the lifting or dilution of the Caesar Act.

Alberto Hernández, a policy officer at the Syrian American

Council, describes Washington as approaching “a decisive moment” on Syria

policy. He expects the full text of the US National Defense Authorization Act

to be released in mid-December, predicting congressional momentum toward ending

what he calls “the sanctions era.”

Speaking to Shafaq News, Hernández says Congress now views

Syria as a potential “reliable partner” on counterterrorism and narcotics. Any

new partnership, he notes, will come with measurable benchmarks that Washington

believes Damascus may be able to meet.

This diplomatic turn reached its symbolic peak when US

President Donald Trump hosted transitional President Al-Sharaa at the White

House—an event interpreted in Western capitals as a clear signal that the era

of total isolation had ended and had been replaced by a conditional engagement

framework with Syria’s new leadership.

Dr. Eliyan Masaad, a Syrian politician and coordinator of

the Secular Democratic Front, says the government has achieved “a breakthrough

in undoing Syria’s isolation and rebuilding balanced relations with the United

States, Russia, the European Union, and Arab states.” He argues that this

reflects growing institutional capacity and a more coherent foreign-policy

approach. Yet even this opening raises the core dilemma of the moment: whether

external legitimacy can endure without internal legitimacy. On the ground, the

biggest questions—security-sector reform, minority rights, and state authority

over volatile regions—remain unanswered.

For many Syrian Christians, the post-Assad transition has

revived long-suppressed grievances. Masaad notes that the last year exposed

“the near-absence of Christians from the public sphere, security institutions,

ministries, and parliament,” calling the previous regime’s policies a form of

structural marginalization. He argues that the new phase must grant Christians

a visible role in the army, security forces, and political institutions, even

suggesting temporary transitional quotas to correct deep imbalances without

turning power-sharing into a permanent sectarian model.

No group embodies the fragility of the transition more than

the Alawites—the longstanding backbone of the security apparatus who suddenly

found themselves outside the very regime that once carried their name.

Village-level clashes on the coast, involving pro-former-regime local groups

and emerging post-war forces, reveal early tensions.

Masaad notes an initial failure by the authorities to grasp

the requirements of social peace, though he believes the government is slowly

developing a more inclusive approach. But the state has yet to articulate how

it plans to integrate thousands of Alawite officers into new security

structures or what political representation coastal regions will have in any

future parliament or constituent body. The risk is that Syria could move from

one-form dominance to reverse

marginalization, deepening sectarian insecurity.

In the Kurdish-led northeast, where the Syrian Democratic

Forces (SDF) control roughly thirty percent of the country—including its main

oil, gas, and wheat resources—the transition faces its hardest test. Dr. Farid

Saadoun, a Kurdish academic and political analyst, describes a fundamental

political obstacle to any breakthrough this year: the unresolved question of

governance.

SDF leaders demand genuine decentralization, while Damascus

insists on wide central authority. This dispute has stalled the implementation

of the March 10 Agreement, signed by Al-Sharaa and SDF Commander Mazloum Abdi,

which was intended as a roadmap for unifying command structures and

administrative authority.

Saadoun tells Shafaq News that any real settlement requires

a long process involving national dialogue on the structure of the state, the

formation of a unity government, parliamentary and presidential elections, and

drafting a new constitution. He proposes a middle formula, more expansive than

cosmetic administrative decentralization but short of political federalism,

allowing broad local powers for provinces, locally elected governors and

councils, and a central government that retains defense, foreign affairs, and

finance.

“Without such a model, northeast Syria could drift toward a

de facto autonomous region operating largely outside Damascus’s political

center of gravity.”

Nowhere is the tension between center and periphery more

vivid than in Suwayda. The Druze-majority province ignited protests in August

2023 over fuel prices under Al-Assad, but quickly evolved into a structured

movement demanding the implementation of UN Resolution 2254, the release of

detainees, and ultimately the regime’s fall—helping accelerate Assad’s collapse

in late 2024.

A year later, Suwayda has not quieted. Organized

demonstrations continue, some peaceful, some involving limited clashes with the

new security forces, and a new discourse has emerged in recent months calling

for “independence” or a special administrative status. Since mid-August 2025,

protests have carried explicit autonomy slogans, marking what local reports

describe as a new stage of Druze mobilization. Observers say the community is

divided between those who want broad decentralization within a united Syria and

those who advocate more far-reaching forms of self-government based on years of

de facto autonomy during the war.

Following the collapse of Al-Assad’s authority, Israel

expanded into the demilitarized zone established by the 1974 Disengagement

Agreement, effectively controlling a broad strip of Syrian territory which it

describes as a temporary buffer. The UN documents hundreds of ceasefire

violations and repeated Israeli airstrikes targeting suspected weapons depots,

Iranian-linked groups, or Syrian army positions. President Al-Sharaa recently

accused Israel of “fighting ghosts” and exporting its post-Gaza crisis into

Syrian territory, calling the buffer-zone expansion an “actual occupation.”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, meanwhile, speaks

of potential arrangements with Syria only if Israel retains a deep buffer

extending from the outskirts of Damascus to Mount Hermon. This dynamic

intersects with Druze grievances in complicated ways. Israel hints at the need

to protect minorities, while Damascus portrays itself as the guardian of

territorial unity.

Inside Suwayda, many Druze view outside protection with

suspicion, fearing it could turn the province into a bargaining chip between

regional powers. The result is a province caught between Syrian government

pressure, Israeli military dominance, and rising local demands for self-rule.

Beyond minority politics and territorial tensions, Damascus

still faces the destabilizing legacy of irregular armed groups, including

foreign fighters and local formations that once fought alongside pro-Sharaa

forces against the old regime or rival factions. The government speaks of

dismantling these structures and integrating eligible fighters, but on the

ground, many groups still control pockets of territory and maintain economic

networks linked to smuggling and informal taxation. Without a clear disarmament,

demobilization, and reintegration strategy, the state will not fully regain its

monopoly on force.

Meanwhile, Syria’s economy remains exhausted after fourteen

years of war that shattered infrastructure, industry, and agriculture. The

currency is fragile, inflation is high, unemployment is widespread, and

hundreds of thousands rely on assistance or remittances. Any recovery plan

requires major infrastructure rehabilitation, reliable energy supply,

reconnection of Syria’s banking system to global networks, and a predictable

sanctions policy. Some experts expect partial easing of the Caesar Act by year-end,

which could allow limited foreign investment. For now, Syria relies on Gulf and

non-Gulf partners to cover salaries and fund selective reconstruction. But

without resolving the political issues of Suwayda, the northeast, and minority

inclusion, large-scale investment will remain out of reach.

One year after Al-Assad’s fall, Syria does not resemble its

2024 self, but it has not yet become the Syria that many protesters envisioned

over the past decade. In the coastal region, Alawites are redefining their

relationship with the state—from rulers to stakeholders. In Suwayda, Druze

communities brandish the flag of autonomy without fully abandoning the idea of

a unified country. In the northeast, Kurds and Arabs under the SDF await a

definitive answer from Damascus about the meaning of decentralization. In the

south, Israel is redrawing its own security lines inside Syrian territory. The

second year of the Al-Sharaa era will not be a continuation of the first; it

will be the year Syria tests the very idea of the state. If the government

succeeds in converting external openness into tangible institutional reforms

and turning the language of partnership with minorities and peripheries into

laws and structures rather than slogans, the coming period may mark Syria’s

slow exit from a long, dark tunnel. If not, Syrians may one day look back at

the fall of Al-Assad as another squandered moment—an inflection point that

promised a new republic but delivered only a rearranged version of the old one.

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.