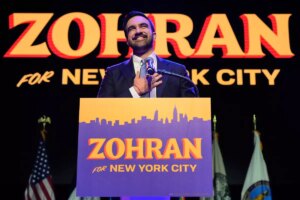

Russell Crowe, best known for his Oscar-winning role in “Gladiator,” delivers a chilling, career-defining performance in the new film “Nuremberg” as Hermann Göring, the highest-ranking Nazi official to stand trial for war crimes at the International Military Tribunal after World War II.

Who was Hermann Goering?

In World War I, Hermann Göring was celebrated in Germany as a fighter pilot and “ace,” reportedly credited with many kills. He later joined Adolf Hitler’s nascent Nazi movement and took part in the failed 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, an attempted coup in Munich. Göring was shot in the groin during the chaos and began taking powerful painkillers; at different points in his life, he struggled with addiction to these drugs.

As the Nazis rose to power, Göring accumulated titles and influence. He became one of Hitler’s closest associates and was best known as the commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, Nazi Germany’s air force. In 1939, Hitler even named him his official successor. Near the end of the war, when Hitler sent word from the bunker that he intended to commit suicide, Göring sent a telegram asking permission to assume leadership of the Reich. Hitler, enraged, took this as a power grab and ordered Göring’s arrest.

The film opens with American forces taking Göring into custody and being stunned to learn that he was taking around 40 pills a day. With Hitler, propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, and SS chief Heinrich Himmler all having killed themselves, Göring became the highest-ranking Nazi official left alive — a rare opportunity for the Allies to put a top leader on trial and force him to answer for his crimes in open court. He was also infamous for amassing stolen art and luxury goods; he arrived in prison wearing jewels, with an estimated fortune in 1945 of more than $200 million.

Crowe told Joe Rogan that playing Göring meant inhabiting a character who was both fascinating and extremely dangerous. He said the role was a major challenge and emphasized that he didn’t want to play Göring as a caricature, but as a charismatic, calculating figure whose charm made him all the more frightening.

What were the Nuremberg Trials?

The film shows that it was not a foregone conclusion that there would even be a trial. In the chaotic period right after Germany’s surrender, some Allied leaders argued that the top Nazi officials should simply be rounded up and shot. Others, however, pushed for a public legal process that would put Nazi crimes on the record and create a lasting precedent in international law, in the hope that nothing like the Holocaust could ever happen again.

Nuremberg was a grimly fitting place to hold the proceedings. It had been a major stage for Nazi rallies, and it was there that Hitler announced the Nuremberg Laws in 1935. Those laws stripped German Jews of their citizenship, banned marriage and sexual relations between Jews and so-called “Aryan” Germans, and defined Jewishness racially: anyone with three or more Jewish grandparents was classified as a Jew, regardless of how they identified.

The trial brought together judges from the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France. Of the 22 major Nazi leaders who ultimately sat in the dock, 19 were convicted, and 12 were sentenced to death for war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity. In the film, we see Crowe’s Göring use his sharp wit and courtroom theatrics to spar with the prosecutors, all while brazenly insisting that he did not know about the “Final Solution” and claiming that he never personally signed any document ordering mass murder — a line of defense he also tried to advance in the real trial.

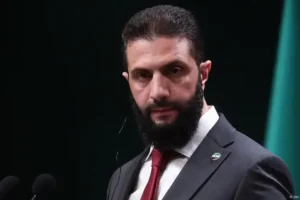

Rami Malek as Douglas Kelley in “Nuremberg”

Beyond the main international trial, the United States later held twelve additional Nuremberg proceedings against doctors, judges, industrialists, and other Nazi officials. In those subsequent trials, 177 defendants were tried, 24 received death sentences, and many others were given long prison terms.

The doctor in the interrogation room

Actor Rami Malek stars as U.S. Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who is tasked with evaluating the 24 Nazi defendants for mental competency to stand trial. In the film, we see Kelley skillfully appeal to Göring’s ego, telling him he needs to lose weight if he wants to avoid another heart attack and present himself as strong and dignified in court.

Kelley is taken aback by how charismatic and charming Göring is, as well as by the way he speaks with almost unwavering loyalty and admiration for Hitler. Crowe and Malek have compelling on-screen chemistry, as the power dynamic between their characters constantly shifts; in one moment Göring seems to control the conversation, and in the next, Kelley quietly reclaims the upper hand.

When Kelley is asked by the prosecution to get Göring to reveal what his legal defense will be, the psychiatrist faces a profound ethical dilemma: should he use the trust built in their sessions to aid the Allied case, or uphold his duty as a doctor, even when his patient is one of history’s most notorious criminals?

Nuremberg’s moral reckoning

One of the most provocative sequences involves U.S. chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson (Michael Shannon) and the pope. Before Jackson has secured approval for the trial, he travels to the Vatican and asks the pope to publicly endorse the idea of putting Nazi leaders in the dock. The pope initially refuses, saying he cannot get involved in political matters. Jackson then delivers what feels like the film’s mic-drop moment: he confronts the pope about the Church’s early agreement with Hitler’s regime and asks why the Vatican was so quick to recognize the Nazi government. The pope replies that he did what he had to do to protect Catholics. Jackson answers, “It’s a pity the Jews didn’t have someone to do that for them.” In the film, this rebuke leads the religious leader to change his mind. The exchange is powerful, even if it appears to be a dramatic invention rather than a literal historical scene.

Actor Leo Woodall portrays Sgt. Howard Triest, who served as a translator. With blond hair and blue eyes, he didn’t tell any of the Nazis that he was Jewish. He had to calm his anger as numerous members of his family were killed in Auschwitz. Woodall gives a moving speech to Kelley, explaining how his family was able to get him out of Germany at the right time, and he later became an American soldier who stormed Omaha Beach as part of the D-Day invasion.

Another haunting moment centers on Julius Streicher, the publisher of Der Stürmer, the most notoriously antisemitic newspaper in Nazi Germany. Der Stürmer was a key propaganda tool: its caricatures depicted Jews as demonic, hook-nosed threats to Germany, and its official slogan, “The Jews are our misfortune,” helped normalize the idea that Jews were subhuman and deserved persecution. In the film, we witness Streicher’s hanging. Moments before he is executed, he cries out, “Purim Fest 1946!”

“Nuremberg”

That chilling reference is rooted in Jewish tradition. On the holiday of Purim, Jews read the biblical scroll of Esther, which tells the story of the evil Haman, who plotted to annihilate the Jews of ancient Persia but was instead executed, along with his ten sons, who were hanged. Traditionally, the reader chants the names of Haman’s ten sons in a single breath, emphasizing their collective downfall. Some Nazis, despite viewing Jews as inferior, were deeply familiar with aspects of Jewish history and feared they might share the fate of previous enemies of the Jews. Rabbi Raphael Shore, in his book Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Jew?: Learning to Love the Lessons of Jew Hatred, notes that Hitler himself had invoked Purim: when he declared war on America, he accused President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Jews of preparing a “second Purim,” and in 1944 he warned that if Germany lost, it would mean a “second triumphant Purim festival.” Streicher’s final words, as portrayed in the film, twist this tradition into a bitter acknowledgment that he, too, was about to become part of that long, dark history.

Based on a book and a creepy coincidence

The film is based on the nonfiction book “The Nazi and the Psychiatrist” by Jack El-Hai. In the book, El-Hai explains that Kelley saw his job not as treating or improving the mental health of the defendants, but simply maintaining it so they could stand trial. After he was found guilty, Göring somehow managed to obtain a cyanide capsule and swallowed it, killing himself before he could be hanged.

Toward the end of the film, we see Kelley thrown off a radio show after he argues that, as cruel as the Nazis were, they were “normal” people who had been radicalized — and that Americans were just as capable of committing similar acts of savagery under the right conditions.

On Jan. 3, 1958, in a chilling real-life echo of Göring’s suicide, Kelley was at home when he swallowed a cyanide capsule and killed himself, ending his life in the same manner as the man he had once evaluated at Nuremberg.

Some moments aren’t magical

A scene in which Kelley teaches Göring a magic trick feels completely out of place tonally and undercuts the gravity of their relationship. Equally jarring are the real photographs of Jewish corpses shown on screen; they are extremely graphic and may shock viewers who aren’t prepared for such images in the middle of a dramatized film.

It’s understood that the movie will take liberties with the historical record for dramatic purposes, but the subplot in which Kelley gets in trouble for a romantic dalliance feels especially contrived and, in fact, isn’t true. In addition, aside from Göring’s wife and daughter, the two main female characters we see — a reporter and a lawyer’s friend — come across as token figures. They appear briefly, serve narrow functions in the plot and then disappear, leaving us knowing almost nothing about them.

Crowe and Malek make “Nuremberg” worthwhile

The pacing is uneven and some characters are handled a bit too flippantly, but the film is still powerful thanks to the magnetic presence of Crowe and the nervous energy Malek brings to Kelley. Malek is at his best when he plays the psychiatrist as quietly inquisitive; when he yells or tries to act tough, those moments feel less credible.

While the movie understandably focuses on the American role in the tribunal, it would have been richer had it shown more of the behind-the-scenes disputes among the Allied countries leading up to the trial. “Nuremberg” is a film Crowe carries on his back, and he carries it well — his scenes with Malek are consistently captivating. By contrast, Shannon and Slattery don’t add much.

The film doesn’t offer a definitive answer to how these men were capable of committing such atrocities, but it does show that once their power is stripped away, most of them appear disturbingly ordinary. Göring is the exception: he is clearly intelligent, though Kelley concludes he only truly cares about his own advancement. This is Crowe’s second-best performance, surpassed only by his iconic turn as Maximus. Directed by James Vanderbilt, “Nuremberg” is a fine film if you care about history and don’t mind a few historical inaccuracies.