Imagine working diligently and saving with the goal of purchasing a home: generally the biggest financial decision a person will make. When house prices rise sharply (and wages fail to keep up), and homeownership becomes less attainable, the incentive to keep saving towards that big goal diminishes.

When housing becomes less affordable, people with fewer resources increase their spending.Credit:

With that aim gone, people tend to spread their spending out more evenly over their lifetime. They draw down on whatever they had started squirrelling away for a deposit, and spend more on other things, especially in the short term.

It also starts to make less sense to endure long hours of work, or put in that extra mile (or 1.6 kilometres, as we would have it). The effort and the cost – feeling tired, missing out on time with family and friends or sacrificing time for self-care – are no longer justified by the future benefit of getting a ticket onto the wealth-building train that is homeownership. It makes more sense for these people to “re-optimise” towards better work-life balance.

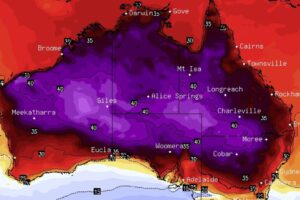

Keep in mind, too, that housing affordability is worse in Australia than it is in the US. While Americans in 2022 needed just under six times their median household income to afford the median house, the median dwelling (not even a house) in Australia was priced at eight times the median household income.

The change in investment behaviour is also strangely intuitive.

Loading

If steady saving and traditional pathways to building up wealth (such as homeownership) are no longer enough – or no longer an option – some households might pursue high-risk, but potentially life-changing, strategies as a last resort.

Those who have a realistic pathway to homeownership tend to be less willing to take on risk because significant losses could derail their progress towards that goal. But those who have given up on it, or who need a miracle to make it happen, might feel they have less to lose, and therefore may be more willing to behave in financially risky ways.

It’s also possible that the longer aspiring homeowners have to put in extra hours (at the expense of living out their youth), it becomes more rational for them to give up. Why spend 10, 20 or 30 years – and possibly forever – sacrificing health or missing out on the youthful experiences, relationships and memories that ultimately lay the foundations and make for a full and happy life? What was once a sacrifice with an end date has, in many ways, become the bigger gamble.

But perhaps the trade-off doesn’t have to be so extreme.

We’ve all heard about the need to improve housing affordability by building more homes and winding down unnecessary tax incentives such as the capital gains tax discount.

Loading

But the American researchers proposed something rather interesting. We know that handing money out to everyone is not useful because it simply pushes up demand and therefore house prices. But targeting these transfers to only the poorest households also does relatively little. Why? Because they rarely move people past the point where they start behaving differently.

Instead, they say a subsidy specifically designed to push the biggest number of young renters above the point of “giving up” on homeownership could bring the biggest and long-lasting benefits: raising homeownership rates and increasing the effort people put in at work at a lower cost than most other conventional policies with the same budget.

Without meaningful efforts to improve housing affordability, we risk destabilising the economy, worsening the wealth gap, dampening productivity and pushing many (once) aspiring homeowners onto a riskier path that could end up costing everyone more.

The logic of ramping up supply and fixing our tax system to improve housing affordability might not be hitting home. But without taking more action – whether conventional or not – we can expect those “lazy” and “undisciplined” young people to keep behaving as they are: rationally.

Get a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up for our Opinion newsletter.