For Greg Steinmetz, the Augsburg, Germany-born Jakob Fugger was “the first person to conduct trade on a truly global scale.”

Steinmetz, a former correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, profiled Fugger in the 2015 biography The Richest Man Who Ever Lived.

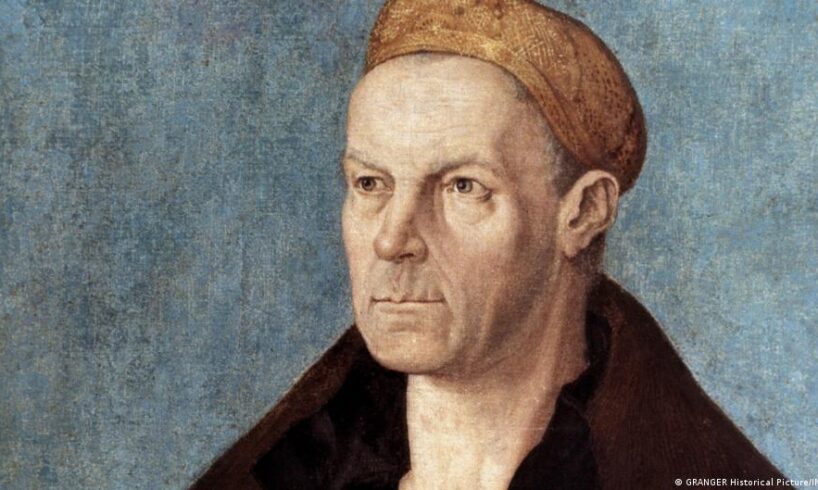

Jakob Fugger was the first merchant to conduct his trade on a global scaleImage: gemeinfrei/Narziss Renner/Wikipedia

Speaking with DW, Steinmetz said global commerce barely existed at the time, until German Emperor Charles V extended European control into South America during his reign as Holy Roman emperor and king of Spain in the 16th century.

There wasn’t much of a globe to trade with, Steinmetz noted, apart from trade with India, and what is now Indonesia and China.

But merchants could only travel west after Columbus had discovered America in 1492, meaning “only half the globe” had been known to Europeans, and Fugger was “at the beginning of that phenomenon” later known as global trade.

How education changed everything

Born into a prosperous Augsburg family whose wealth began with his grandfather, master weaver Hans Fugger, Jakob received his commercial training in Venice, Italy. The city not only shaped Jakob’s taste for the Renaissance but also introduced him to a breakthrough that would accelerate his rise: double-entry bookkeeping.

Since there were no business schools back then, Steinmetz said, merchant families would “send their boys out to become apprentices,” and Germans heavily traded with Venice.

“He [Fugger] took all of those Venetian secrets, including double-entry bookkeeping, back to Germany with him. And he was the first in Germany to employ these modern methods,” Steinmetz said.

Fuggerei, world’s oldest social housing, turns 500

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

With meticulous records, Fugger always knew where his finances stood — unlike many rivals. He also built an intelligence network of agents across major European cities and even small German towns.

“People would feed him with information, by courier and horses … so that he would know about things before his competitors did, and he could use that to his advantage. Information today is everything, and it was everything back then, too,” Steinmetz said.

Banker to emperors

After his brothers died, Jakob Fugger took sole control of the family enterprise in 1510 and strengthened its ties to the Habsburg monarchy, lending aggressively to Emperors Maximilian I and Charles V.

In return, he secured access to lucrative silver and copper operations in Tyrol and what was then Hungary. He did not own the mines outright, but held rights and stakes that proved extraordinarily profitable.

Fugger’s city palace in Augsburg is testimony of the merchant family’s wealth and powerImage: Martin Siepmann/imagebroker/IMAGO

Europe had little to offer Asia at the time besides precious metals. “Europe wasn’t exporting technology or luxury goods,” Steinmetz explained. “But it had silver, gold, and copper — and that’s where Fugger became indispensable.”

Copper powers an empire

Martin Kluger, CEO of the Context publishing house in Augsburg and Nuremberg, and also an author of several books on the Fugger family, said India — then technologically and economically ahead of Europe — suffered a chronic shortage of copper, which was a “stroke of extremely good luck” for the Fugger mining interests.

And timing amplified that advantage: “Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route to India in 1498, just three years after the Fuggers moved into large-scale copper mining in Neusohl [today Banska Bystrica in Slovakia]. Demand soared, and the Fuggers held the supply,” said Kluger.

How German merchants shaped Africa’s fate

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Copper consumption was rising in Europe as well — in shipbuilding, weaponry, cookware and monumental architecture. Kluger noted that the Habsburgs and the Hungarian crown often repaid debts by granting mining rights because they lacked other means.

“The aristocracy’s limited commercial knowledge worked in the Fuggers’ favor,” he added.

Fugger also ensured that powerful yet hugely indebted borrowers kept paying. His strategy, Steinmetz said, was to “make himself indispensable.”

“Emperor Maximilian was constantly fighting wars and had to pay mercenaries. The only one who could come up with money when Maximilian needed it quickly was Fugger.”

A legacy that endures

Lars Börner, a German economic history expert, believes Fugger reshaped European finance because he persuaded the pope to relax the Catholic Church’s ban on charging interest, which opened the door to modern lending practices.

“It’s no secret that the pope also liked to pull in the highest returns possible. Interest ban or not,” Börner recently told German public radio Deutschlandfunk.

In exchange, he said, Fugger shared in church revenues, including the controversial sale of indulgences used to fund St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome — a practice that eventually sparked Protestant revolt, the Reformation.

Yet Fugger’s most visible legacy is situated in his Bavarian hometown of Augsburg: the so-called Fuggerei, the world’s first social housing complex, founded in 1521.

It still operates today, and like 500 years ago, residents pay only a nominal rent. Visitors from around the world tour the community, which remains a tangible symbol of his influence.

The Fuggerei in Augsburg, where tenants today pay less than a euro rent enjoying the same privilege as generations beforeImage: Michaela Stache/AFP/Getty Images

Historians estimate Fugger’s total wealth at the equivalent of $300 billion to $400 billion today (€255 billion to €340 billion). In Fugger’s time, this amounted to between 2% and 10% of the entire economic output of Europe — and well above the current wealth of Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos in comparison to the US gross domestic product.

While modern-day philanthropists such as Bill Gates work to shape their legacies through foundations, corporate historian Boris Gehlen told DW they are unlikely to match Fugger’s long-term impact. “Their legacy won’t be as significant as Fugger’s,” he said.

This article was originally written in German.