On their day off, three Ukrainian servicemen – Turyst, Shvaiher and Bublyk – take a minivan up one of the hills in Donetsk Oblast. They unload a couple of comfortable folding chairs and spread out snacks they bought in a nearby frontline shop.

Energy drinks, crisps, kabanos sausage sticks, the soft lilac sky with the faint outline of the moon and mosquitoes biting their bare arms – a typical evening in Donetsk Oblast. It’s not just a place of death, but also of life for hundreds of Ukrainian soldiers.

The men joke amongst themselves that they’ve come here to go fishing. Where else would they spend their day off?

Advertisement:

Only here, the “river” is the vast, endless sky. Ask anyone who’s fought in Donetsk Oblast what that sky is like, and they won’t talk of air-raid warnings, strikes or phosphorus. They will tell you it hangs low, filled with countless stars at night and, in the morning, the most eagerly awaited sight of all – a blazing orange sun. And they won’t be lying.

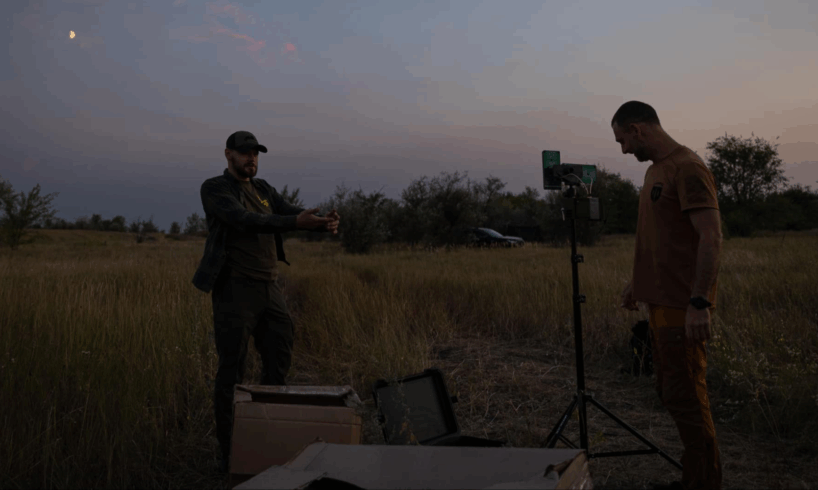

The Signum crew getting ready for work on a summer evening.

photo: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

The Signum crew getting ready for work on a summer evening.

photo: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

On this fishing trip, the “catch” is Russian Shahed drones, and the “fishing rods” are Ukrainian interceptor drones.

When they’re not fighting in the Serebrianka Forest, where the Signum UAV battalion covers the frontline positions of the 53rd Brigade and neighbouring units, Turyst, Shvaiher and Bublyk spend what’s supposed to be their rest time shooting down Shahed drones. Officially, that isn’t even their job as part of the line unit. Their job is to strike Russian infantry, positions, equipment and reconnaissance UAVs.

Intercepting Shahed drones is their own initiative – and, in a way, their hobby.

Inside the Signum van are a table, a tablet, an antenna and their latest prize: five Ukrainian-made interceptor drones in cardboard boxes. At first glance they look like miniature missiles with four engines. In fact, as the Signum engineers explain, they are simply an unusual model of FPV drone.

“Soloma”, an engineer at the Signum workshop, explains: “The radar station guides the pilot to the target and shows its movement. The pilot flies above the Shahed drone, with the camera underneath, and has to pick it out visually. He needs to find the Shahed before it reaches its target, because once it does, it accelerates even more.”

An interceptor drone being prepared for launch

photo: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Unlike conventional FPVs or fibre-optic FPVs – which need to be reflashed to the right frequency or fitted with a 3D-printed reel – these drones require almost no modification. Because they move so fast, they are also not test-flown beforehand, unlike standard FPVs.

That means the Signum workshops actually have the least work to do with them.

“This Ukrainian drone is still in development. It would help a lot to have additional guidance systems, because right now there’s too much manual work and too many chances for human error. And skilled pilots who can really handle these are very hard to find,” Soloma adds.

Signum engineers inspect the interceptor drones before departure

photo: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Just before midnight, Turyst – the first Signum pilot to master interceptor drones – spots a wave of Shahed drones entering from Russian territory on his tablet. Unfortunately the first two get past them, and the rest – dozens of drones – pass outside Signum’s zone, heading towards Kharkiv Oblast.

The shift that Ukrainska Pravda was present at is more the exception than the rule. In a little over a month, the Signum guys have downed 22 Shahed drones – five of them in a single night – in what they call their “free time”.

This is the story of why the Signum crew have chosen to spend their time downing Shahed drones, how they do it, and whether their experience could be scaled up for other FPV crews or even civilian volunteers.

Advertisement:

What role do interceptor drones play in Ukraine’s air defence system?

Since 2022 – and especially from 2023 onwards, when Russia began launching large-scale Shahed drone attacks on Ukrainian cities in the rear – Ukraine’s defence forces have developed several ways of downing Russian drones.

These range from the simplest and cheapest options, such as mobile fire groups (MFGs) that patrol strategic sites and along potential flight routes armed with machine guns and anti-aircraft systems, to far more complex and expensive systems: Western-supplied surface-to-air missile systems such as IRIS-T, NASAMS and Patriot, and the long-awaited F-16 fighter jets.

At first, mobile fire groups – effective at altitudes of 800-1,500 metres – achieved solid results. Their use was scaled up nationwide, and even volunteer territorial defence units, essentially semi-civilian fighters from hromada volunteer associations, were brought into the effort. [A hromada is an administrative unit designating a village, several villages, or a town, and their adjacent territories – ed.]

But by 2024, and especially in 2025, the Russians had begun flying Shahed drones higher, at altitudes of 2,500-3,000 metres – out of reach for the MFGs. Their effectiveness plummeted as a result, though few openly admit it.

“Now mobile groups account for practically nothing in the overall figures, even though there are several thousand people working in them across the country,” one official involved in drone defence told Ukrainska Pravda.

This summer, Ukrainska Pravda spent time with one such MFG crew, fighters from the Lisovyk hromada volunteer association, in Sumy Oblast. We saw firsthand how a Turkish-made Canik M2 machine gun was unable to swivel the full 90 degrees needed as a Russian UAV passed overhead. And even if it had been able to, it wouldn’t have reached the Shahed’s altitude anyway. Crews around Kyiv Oblast, however, insist that their success rates are higher than in other areas, since many drones approach Ukraine through this region.

Fighters from the Lisovyk hromada volunteer association on duty in Sumy Oblast, June 2025

photo: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

There just aren’t enough Western-made anti-aircraft missile system launchers, or missiles for them, as President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has publicly acknowledged. What is more, using million-dollar missiles against Shahed drones that only cost Russia between US$70,000 and US$200,000 is prohibitively expensive.

The first intermediate option (in terms of complexity and cost) between MFGs and fighter jets was helicopters, and more recently interceptor drones have joined them. Ukrainska Pravda has information that helicopters and interceptors now account for the biggest share of shootdowns.

There is little open-source information about the interceptor drones used by Ukraine’s defence forces. Some were purchased from billionaire and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, who personally met with President Zelenskyy in early July. Schmidt and then-Defence Minister Rustem Umierov signed a long-term strategic partnership agreement.

In fact, that meeting between Zelenskyy, Umierov and Schmidt was not the starting point of the cooperation between Ukraine and Swift Beat. An Ukrainska Pravda source in arms procurement says Ukraine has been contracting these interceptor drones since at least last spring. However, the more advanced models, with automatic target guidance, have only been contracted for about two months.

Advertisement:

The strike rate of Schmidt’s interceptors that are used by the Unmanned Systems Forces is reported to be extremely high. This is thanks to the automatic target guidance feature and the drone’s high speed – about 300 km/h. The pilot’s level of training plays only a minimal role.

This is a brilliant technical and financially viable solution for Ukraine: a Swift Beat interceptor drone costs US$5,000-10,000, which is 14-20 times cheaper than a Shahed. However, the effectiveness of this solution depends to a great extent on the manufacturer’s production capacity and its ability to continuously improve the interceptors, especially if Russia begins mass-producing jet-powered Shaheds, which can reach speeds of 600 km/h.

In addition to the centralised and rather slow top-down search for solutions to counter Shaheds, there is also a bottom-up movement within the defence forces.

Several enthusiastic UAV units are trying to learn how to shoot down Russian Shaheds themselves. They use Ukrainian-made FPV drones, which do not currently have automatic target guidance. In other words, whether a Shahed is hit or missed depends on the drone’s technical characteristics and, to a large extent, on the skill of the pilot. He has to be a true virtuoso – a master of FPV.

And Signum, the unit we mentioned at the start of this article, is one of these units.

How hard is it to down Shaheds with interceptor drones, and what does Formula 1 have to do with it?

These are the words of “Turyst”, an FPV operator from the Signum unit who shoots down Russian Shaheds over the logistics base in Donetsk Oblast.

“I downed my first Shahed on 11 July 2025, and to celebrate that moment, I smoked a cigar I’d been saving for a few months. I’d taken it on holiday with me to Madeira and waited for the right moment. I proposed to my girlfriend there, she said ‘yes’ and I thought, okay, I’ll smoke it then, but I forgot. And now its time had come.

In three working days we’d downed seven Shaheds. That’s not a lot; we could have shot down more, but we ran out of equipment. If we’d had 20 drones, we would have downed 20. The Shaheds were flying over us one after another. It takes two minutes from takeoff to shootdown. Launch – down, launch – down.

There was a missile system operating near us on those first successful days. It launched one missile that hit, then two more – and they both missed. Meanwhile we were hitting every time.

Turyst, an interceptor drone pilot, getting ready for work inside the Signum van

photo: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Before our first successful hit, we had about a month of attempts, but they all failed – our interceptors were too new. At first, the Shahed would be flying at about 170 km/h, while I’d be going at 300 km/h, so I’d overshoot it. The battery would drain. The Shahed would blend into the terrain and I wouldn’t be able to find it. The engine would burn out. You can see it, but you can’t destroy it – and that’s horrible!

And then we downed the first one, then the second – five in one go. Suddenly there was less anxiety, which meant less human error.

We took the initiative in this matter ourselves. I said to the battalion commander, ‘Give me a week and a half, and we’ll get results.’ He said: ‘Go ahead.’

Advertisement:

How did it all start? Formula 1 races are filmed with drones flying at 300 km/h. I thought: if there’s a Shahed flying at 170-200 km/h, and a drone flying at 300 km/h, why not combine the two?

I’d already suggested this a year ago. I talked to one, two, three Ukrainian manufacturers, but no one took what I said seriously.

Then the CEO of Company N [a Ukrainian manufacturer, name withheld at the unit’s request – ed.] told me: “We have an equivalent to those drones that are used in Formula 1, but no one wants to use them. ‘I said: ‘Give it to me, I’m dying to have a go!’

So this wasn’t a new technology; the solution already existed. The guys just attached a rotating camera and explosives and extended the flight time. Nothing new had to be invented. But once again, as a state, we moved too slowly; we didn’t think of it in time.

We have a huge problem with innovation and technology development.

Over 200 Shaheds have already been downed by various units using drones from this manufacturer.

Our current problem is scaling up – there aren’t enough drones.

Training crews isn’t hard. Yes, it’s a peculiar drone in some ways – it flies fast, slightly diagonally, but it can also fly parallel to the ground. But essentially it’s a regular FPV, just one with an aerodynamic body and a reinforced engine. A pilot who already flies FPVs can master it.

Before the first missions, I called the manufacturer and said: “Send me the instructions,” and they replied: “Just try it.” I tried and realised it was possible. It’s even easier than shooting down reconnaissance drones, because that whole area has already advanced, including the tactics of use.

Basically, a Shahed is a giant square wing. You fly straight at it: no difficulties.

Advertisement:

Now the issue of interceptor drones has started developing. The government will be funding it, and I’m pleased about that, because everything shouldn’t depend solely on volunteers. Right now all our drones are supplied by Sternenko [the Sternenko Community Foundation] – we’re a mechanised brigade, we can’t afford this ourselves.

Shooting down Shaheds isn’t actually our job – we’re responsible for the line of contact, for our brigade’s sector.

But after a Shahed fell near my home in Kyiv, it became my job, my problem too. If I can stop it here, I have to do it. I have to prove that it’s possible.

A lot of companies and government agencies are interested in interceptors now – they can see the benefits, they understand this is something that has to be pursued. They call me – I’m always glad to help, I say: ‘Give us the resources, the people – we’ll train them, and let them work.’

We’re ready to train territorial defence forces, civilians, anyone.

Right now, Shaheds are the number one problem for civilians. There are constant attacks, even in Sloviansk. The Russians have significantly increased the number of drones they launch.

There’s no point MFGs shooting them down with machine guns; they can’t reach Shaheds flying at 2,500-3,000 metres. When I see them nearby on duty, they’re just sitting there. These people are getting supplies, salaries, vehicles – but what’s the result?

I’ve seen the monthly statistics on drones downed by MFGs in one oblast, and it’s hardly any. And in some cases, it wasn’t even the MFG that downed them – they were jammed by the electronic warfare system, but the MFG still claimed it was the result of their work.

Meanwhile, a civilian kid could sit at an interceptor drone, fly 50 training hours, then take sapper-fitted equipment and knock down those Shaheds one after another.

A Ukrainian drone like this costs under UAH 100,000 (about US$2,400). Compared to the Western missiles that are being fired at Shaheds, that’s peanuts.

Now people have started claiming that the Russians are launching jet-powered Shaheds that supposedly go at more than 400 km/h, and saying that’s why there are so many attacks on Kyiv. But I think that’s an excuse to cover up the clumsiness of our air defence.

Shaheds fly at 3,000 metres – we have no missiles, and the MFGs are powerless. Only drones can help.

photo: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Author: Olha Kyrylenko, Ukrainska Pravda

Translation: Yuliia Kravchenko, Tetiana Buchkovska

Editing: Charlotte Guillou-Clerc, Teresa Pearce