Australian inventors have developed technology that detects potential power line faults, like the one that sparked a deadly Black Saturday bushfire, before they happen.

Created by researchers at RMIT University, Early Fault Detection (EFD) has been trialled in Australia and overseas in a bid to prevent a repeat of the nation’s worst bushfire disaster.

IND Technology, which commercialised the invention, wants to see it rolled out nationally.

But there are limitations.

The Early Fault Detection system listens to radio frequencies on power lines to detect faults. (Supplied: IND Technology)

Ahead of the next disaster season, energy providers are weighing up the benefits against the $380 million installation bill.

The system

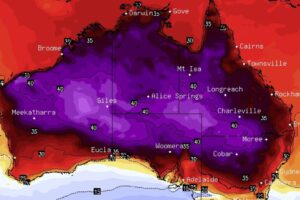

On February 7, 2009, a fire started in Kilmore East, 65 kilometres north of Melbourne, when a faulty power line was brought down in powerful winds on a hot, dry, 46 degree Celsius day.

The 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission found the Kilmore East blaze was caused by an ageing power line. (Supplied: Wade Horton)

It went on to merge with another fire before ravaging Victoria; 173 people died, and more than 400,000 hectares of land was burnt, destroying homes, infrastructure and farms.

The failure of the power line has been scrutinised by a Royal Commission and was the subject of a $500 million class-action lawsuit.

“That fire definitely would not have happened if EFD had been installed,” IND Technology chairman Tony Marxsen said.

Trained as an electrical engineer, Dr Marxsen worked for Victoria’s government-owned electricity provider for 30 years before it was privatised in the early 1990s.

He then worked as a consultant and in academic research.

A house is impacted by the Black Saturday fires at Kinglake in February 2009. (Supplied: April Harrison)

He said EFD was not connected to the network but listened to it, identifying defects like broken wires or vegetation across the line by the radio frequencies they gave off.

“It finds problems, locates them and allows the network owner to go directly to the site and fix the problem before it develops into a full-scale network fault,” Dr Marxsen said.

He said it could detect the fault within 10 metres of accuracy.

“Picking up those radio frequency signals at more than one location, we can triangulate exactly where the problem is,” he said.

Alan Wong , Andrew Walsh and Tony Marxsen lead the IND team. (Supplied: IND Technology)

He said the idea was to fix the problem before the line broke, which could expose live wires that started fires if they hit power poles or the ground.

“If you’re talking about very high fire risk weather, they always involve strong winds, so that’s maximum strain on the wires on the network and that’s when they break,” he said.

“We find the problem before it happens and once again the utility can go out and fix it and prevent the fire.”

The trials

Fallen power lines are not the leading cause of bushfires in Australia, but they are a common source of ignition.

EFD was created as a result of the Black Saturday bushfires. (ABC News: Keely Johnson)

There are several types of power lines, including overhead and underground.

Transmission lines carry high voltages from power generators to substations, which use lower voltage distribution lines to connect homes and businesses to the grid.

EFD technology is designed for single wire earth return (SWER) powerlines, which in Australia are primarily used to distribute power in rural and remote areas, such as Kilmore East.

In the aftermath of that disaster, the Bushfires Royal Commission recommended Victoria’s 28,000 kilometres of SWER lines be replaced.

Distributor Powercor is responsible for 21,000 kilometres of them, which spokesman Jordan Oliver said were protected by several different technologies, including EFD.

“SWER makes up around a third of the Powercor network,” he said.

Vegetation touching power lines can spark fires. (Supplied: IND Technology)

“It was rolled out from the 1950s as an efficient and fast way to provide power to remote and rural areas.”

Several electricity providers in other states have either trialled, or intend to trial the technology, including the largest electricity distributor on the east coast, Ausgrid.

In Queensland, which has about 65,000 kilometres of SWER powerlines, the state’s government-owned electricity company decided not to proceed with a rollout.

While the devices worked, a spokesperson said the cost to install them outweighed the benefits.

EFD can detect small faults on powerlines that can not be seen by the naked eye. (Supplied: IND Technology)

In 2020, Endeavour Energy was the first of three energy distributors in New South Wales to trial EFD.

Head of asset management, Edmund Li, said the trial had helped identify deterioration in hard-to-reach locations.

“The network goes through areas which aren’t necessarily on the side of the road,” he said.

“It’s more difficult if we’re purely relying on visual inspection techniques.

“We may not be able to find some of those issues.”

Who’s paying for it?

Most energy distributors send proposals to the Australian Energy Regulator outlining how they plan to operate, maintain and fund their networks every five years.

The EFD system uses radio frequencies to find small faults. (Supplied: IND Technology)

Mr Li said Endeavour Energy’s latest submission included funding for EFD devices on about 1,000 kilometres of their network.

“We’re being judicious in how we invest in our network and these sorts of technologies to provide ongoing benefits to our customers,” he said.

In Victoria, network operator Ausnet has 310 EFD devices installed and included $20 million in its proposal for a broader rollout.

Powercor’s submission included $13 million to use EFD as part of safety improvements on the SWER network.

Last year, the researchers behind the technology called for a national rollout, which Dr Marxsen estimated would cost about $380 million.

EFD is being rolled out across New South Wales and Victoria. (ABC News: Adriane Reardon, ABC South East NSW: Adriane Reardon)

In the meantime, he said the technology had been embraced overseas.

“About 98 per cent of our production goes to North America, the US and Canada, but we are starting now we have installations in Asia and Europe,” he said.