BEIJING – A new catchphrase is sweeping China’s social media: The Beauty of the Boom Years.

Using apps such as RedNote and Douyin, people are reviving memories of the 2000s and the early 2010s with photos of daring outfits, upbeat songs and vintage TV commercials, all of which, in different ways, evoke a time in China that pulsed with optimism.

“The music back then throbbed with exuberance, brimming with the sense that the future could only get brighter,” a middle-aged man said in a RedNote video.

“Today’s lyrics begin with lines like, ‘We’re trying our best to survive’.”

Others reminisced about fashion. “Twenty years ago when I was in college, I wore camisoles and hot pants,” wrote a female RedNote user under the hashtag #BeautyOfTheBoomYears. “These days, students dress more like nuns, always draped in oversized clothes.”

Using the hashtag, Chinese who started their careers two decades ago brag about when they received multiple job offers with generous year-end bonuses. Younger users respond with oohs and aahs, remembering their childhood, a time when China felt livelier, cosier and full of possibility.

The phrase expresses a longing for an era when China’s economy was roaring ahead and, for many, optimism was almost second nature.

It doubles as a commentary on the country’s mood today. It especially speaks to China’s younger generation, who are grappling with an economic slowdown, record youth unemployment and tighter social controls.

“Perhaps what we miss is not a ‘golden era’, but the courage to believe the future holds promise,” read an editor’s note on an article headlined, “How Beautiful Was the Boom? Back Then a Job Hop Meant a 30% Raise. Now Civil Service Exams Are the Only Way Up”.

Nostalgic hashtags such as #Millennium, #ChineseDreamcore and #BeautyOfTheBoomYears have drawn more than 10 billion views across the Chinese internet, according to the data firm Newrank. On Douyin, the short-video platform, the tag #UsingFashionToShowTheBeautyOfTheBoomYears has racked up over 210 million views.

China’s boom years are often dated to the country’s entry to the World Trade Organisation in 2001. They signified entrepreneurial energy, rising living standards and abundant career opportunities. The mood was captured in the titles of a hit song, Tomorrow Will Be Better, and a popular television drama, Strive.

Optimism was not just aspirational. It felt rational. Many believed that with hard work anyone could become the next Jack Ma, the Alibaba founder.

Where those years encouraged risk-taking, today’s environment leans towards caution.

Civil-service jobs, once considered staid, now dominate the conversations of young people looking for havens in a shrinking job market.

A carousel post on RedNote contrasts the two eras. Then, lighthearted romantic comedies and buoyant advertisements. Now, heavier dramas and therapeutic ads mirroring a society weighed down by pressure.

Fashion tells the same story. In the 2000s, young women favoured camisoles, short shorts and bright red lipstick. Now the prevailing look is oversized and concealing: long skirts, sun visor caps and UV protection hoodies.

“It’s as if they’re shielding themselves from a harsher world,” another RedNote post said.

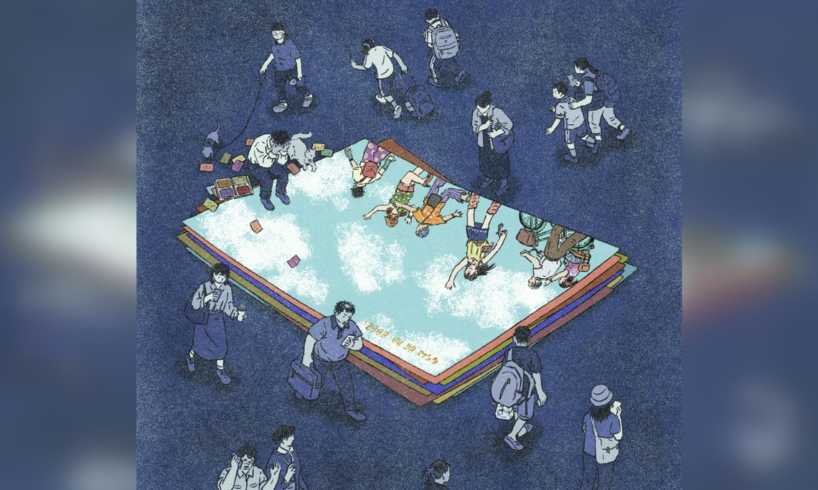

The boom-time beauty meme is the latest expression of a Gen Z counterculture born of disillusionment, the recognition that they may be the first generation in half a century unlikely to surpass their parents’ standard of living, no matter how hard they try.

Over the past five years, this quiet resistance has taken many forms.

It began with “lying flat”, a refusal to join the rat race. Some chose to pursue the “run philosophy”, or emigrating in search of freedom and brighter prospects. Others declared themselves the “last generation”, vowing not to have children.

Still others embraced “let it rot”, giving up on difficult goals rather than battling for uncertain rewards. To show they couldn’t care less about career prospects, many took to wearing “gross outfits” at work.

Now the focus has turned to celebrating the beauty of the boom years, an implicit criticism of the present.

Youth discontent worries governments everywhere. Last week in Nepal,

Gen Z protests over corruption and inequality forced out the country’s prime minister

. In China, it was largely college students and young professionals who participated in the White Paper protests of late 2022, helping to end the harsh “zero-Covid” policy.

Beijing keeps a watchful eye on even the subtlest resistance. In a 2022 editorial, People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s official newspaper, scolded young people for “lying flat”. In 2023, as one in five young Chinese was jobless, the country’s leader, Mr Xi Jinping, called on them to “eat bitterness”, a phrase that means to endure hardships.

So far, the authorities seem to have allowed the boom-year nostalgia to circulate online, perhaps happy to instil some optimistic energy into the young generation. But for Gen Z, it is easier to be nostalgic about the past than upbeat about the present.

Growing up in a small town in the southern province of Guangxi, Mr Wei, now 34, remembers his teenage years as an age of glitter. He carried a phone charm that lit up like a magic wand with every call.

“People wanted to shine because they wanted to be seen,” he said. “To be seen meant more opportunities.”

Today Mr Wei, who asked me to use only his family name for fear of government retribution, works as an engineer in construction. He calls it a “sunset industry”, since China has already overbuilt much of its infrastructure, particularly housing.

Single and with no plans for children, he sees little future in the life he once imagined, saying his optimism has disappeared as he has found it harder to speak his mind publicly.

Ms Cora, a 25-year-old Beijing native, cherishes childhood memories of chatting with mum-and-pop food stall owners after school in the early 2010s. “They were simply making a living, yet each radiated contentment,” she said.

Those stalls are gone, cleared in what city officials said were campaigns to beautify the streets and drive out the “low-end population”. Places that once carried people’s dreams and livelihoods and sweat and emotions were turned into lawns, she said.

Ms Cora, who asked me not to use her surname, emigrated to Canada in 2022, giving up on her dream of working in one of Beijing’s skyscrapers.

Mr Will Yu, 29, grew up idolising China’s tech companies. He devoured stories of generous pay packages, overseas retreats and canteen meals prepared by five-star chefs.

When he joined a big firm in Shanghai in 2021 as an interactive designer, those kinds of perks had vanished. He worked long hours churning out one sales promotion design after another. He felt he had little hope of advancing in his career.

After two years he quit and moved to Germany. He was struck by how limited China’s social safety net and legal protections were by comparison.

“Our generation mistook growth for progress,” he said. “A healthy society needs fairness, freedom and respect for every individual.”

As a gay man, he once believed that money could help overcome social and political constraints, until he witnessed the government’s crackdown on the LGBTQ community.

“Everyone is competing for first-class seats on the Titanic,” Mr Yu said. “But few stop to ask where exactly the ship is headed.” NYTIMES