Even as Israel faces unprecedented criticism following the war, Rabbi Oury Cherki remains convinced that reality differs from current perceptions. In his view, the current wave of hatred stems not only from images emerging from Gaza but connects to a deeper layer: the Jewish people’s place in humanity’s “collective unconscious mind,” as he describes it.

“The world is trying to atone for the Holocaust, which is a certificate of failure for Western civilization, by portraying Israelis as ‘the new Nazis,'” Rabbi Cherki states. “Notice that there’s no indifference toward us – either they hate or love, but never ignore. This attitude expresses humanity’s adolescent crisis facing us. The time will still come when they understand our true role – a conduit for the divine word’s appearance in the world. When this happens, the world will come here to hear Judaism’s perspective on the great questions of human existence. We’ll then need a new intellectual-Torah elite that can translate our fundamental values into a universal language. This is exactly what we’re trying to produce now. Will we succeed? I believe so.”

When Rabbi Cherki discusses cultivating an intellectual-Torah elite, he primarily refers to the “School for Wisdom of Faith” he established, whose sixth cohort will soon begin. The program consists of a two-year track with one day of weekly study, featuring prominent lecturers from the rabbinical and academic worlds. The goal, he explains, is to “shape the next social pyramid’s apex,” serve as an address for “clarifying Israeli society’s fundamental values,” and create a counterweight to research institutes associated with the left, such as Van Leer and the Israel Democracy Institute.

“Those engaged in spreading Judaism today focus mainly on folklore – Shabbat candles, tefillin. These are important things, but they don’t touch society’s fundamental questions,” he explains. “We want to develop people who can take responsibility and stand in the future at the center of public and global discourse.” The initiative was born, he recounts, following a close friend’s comment: “He told me ‘you teach everywhere, but haven’t established a serious framework for studying faith.’ I replied ‘there are yeshivot,’ and he responded ‘true, but they don’t really deal with this seriously.’ I understood he was right.”

Q: Religious Zionist yeshivot do study “faith.”

“About sixty years ago they invented the concept ‘Jewish thought,’ intended to replace ‘Jewish studies.’ The Mercaz HaRav [institution] didn’t like this term; it claimed that Judaism isn’t philosophy, it’s the divine word. Instead it promoted the expression ‘faith studies.’ In practice, ‘studying faith’ became synonymous with lack of deep thinking. There are several chosen books that need to be reviewed and one needs to know how to deliver lessons on them, but the idea of really thinking about faith’s fundamentals was pushed aside. HaRav Kook repeatedly emphasized the need to establish a ‘higher house for wisdom of faith,’ a place where the believer knows how to think, and the thinker also knows how to believe. This is the elite we’re trying to produce here.”

Rabbi Cherki’s daily routine is particularly packed: sixteen regular weekly lessons, alongside conference appearances and interviews in the media and various podcasts. He ranks among the most balanced rabbis online: his YouTube channel has accumulated over 3 million views to date. Despite this workload, he radiates calm and ease. “Recently I even managed to get a bit bored,” he says with a smile. Occasionally, he finds time for classical music, mainly Beethoven, and insists on sitting and listening, not hearing on the road in the car. “I respect it too much for that.”

Q: Many of your lessons deal with faith’s great questions, and the impression is that you “know everything,” pulling out immediate answers. Do you also have cracks as a man of faith? Unresolved questions?

“I don’t know everything, I know a lot. I simplify: My talent is taking deep content and laying it out for the listener. But cracks? Certainly. In my opinion, whoever claims everything is clear to him is lying. No person doesn’t ask questions in faith. Ultimately, every person lives with a fundamental question. My question is, ‘what exactly does God want,’ what’s hidden behind the things He does. Some kabbalists spoke of divine delight and saw reality as a kind of game between groom and bride. It’s a riddle, maybe after one hundred and twenty [years] I’ll receive an answer about it.”

Q: Is there a heretical book that left an impression on you?

“‘Alma Di’ by Ari Alon. A wonderful heretical book, challenging, full of content. He describes there one Saturday when he woke up in the morning and wanted to kill God, his fierce desire to tear the eruv wire. I see here a demand for a broader world.”

“I deliberated whether to be a gardener”

He was born 65 years ago in Algeria, to Chaim-Gedalia, a doctor of economics, and Batya-Albertine, a Holocaust survivor. His parents met in France, and after several years of living in Algeria and France they immigrated to Israel in 1972. His grandfather, Ezer Sharki, who was president of Algeria’s Zionist Federation, was close to Rabbi David Ashkenazi, Algeria’s chief rabbi. The family connection continued in the next generation, with his son Rabbi Yehuda Leon Ashkenazi, “Manitou,” one of the catalysts of Jewish revival in France.

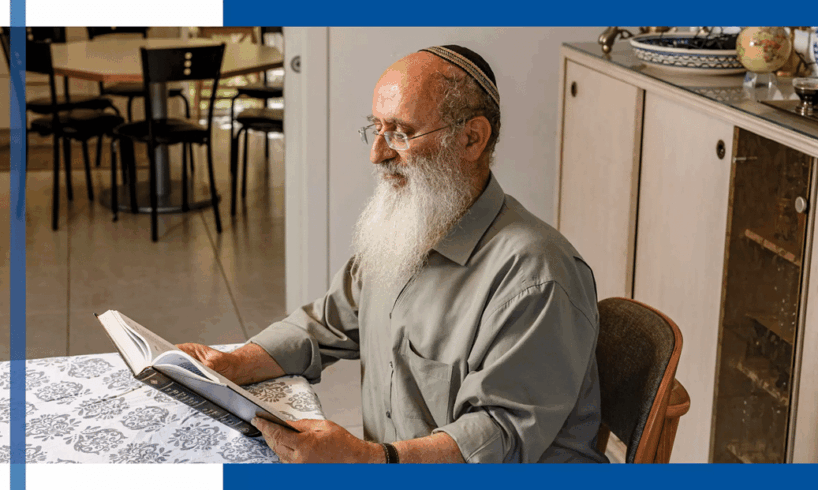

Rabbi Oury Cherki with students (Photo: Courtesy of Brit Olam)

“I knew Manitou even before I was born,” Rabbi Cherki smiles. “Already in childhood, I heard about him at home. I remember the first meeting with him in Israel, at age 11, to this day as a formative event.”

Manitou’s influence is clearly evident in Rabbi Cherki’s entire body of teaching, and also in his latest book, the eighteenth in number, for which we’re meeting. The book, “My Name Preceded,” contains commentary on the first half of the Book of Genesis, and it’s part of a nine-volume series on the Five Books of Moses that will be published later.

“Rabbi Ashkenazi (Manitou) used to say that the Torah teaches what a Jew does, but only the Book of Genesis answers the question ‘what is a Jew,'” Sharki states. “Everyone is searching for identity today, not only in Israeli society but in the entire world. This is a period of confrontation between cultures and tectonic changes in world order. Therefore, the Book of Genesis is the most important book in our era.”

According to his interpretive method, the Bible cannot be understood without the mystical Torah. “The Bible is not a history or philosophy book but prophetic words. Specifically, the Kabbalah sages preserved this understanding. Therefore, the kabbalistic reading is not a later addition but a key to the true, simple meaning. And when this is clear, using literary, historical, and even comparative tools doesn’t harm holiness but deepens understanding. What makes understanding the Bible difficult is that it was written in prophetic Hebrew, in an era when there was prophecy in the world. In Kabbalah, we retained a remnant of the prophetic spirit. If you’re talking about a mystical world, in the biblical period it was revealed.”

Q: Researchers will say you took later developments in Kabbalah and imposed them on the Bible.

“The formulation came later, but the living spirit that passes through these formulations is ancient.” Upon his immigration to Israel, Sharki studied at Netiv Meir high school yeshiva, and already at age sixteen, established his place in Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook’s lessons. Later, he studied with a diverse range of rabbis: the kabbalist Rabbi Meir Yehuda Getz, the kabbalist Rabbi Shlomo Benjamin Ashlag, son of the “Baal HaSulam,” and Rabbi Zvi Tau, leader of “HaKav Yeshivot.” He lives in the Givat Shaul neighborhood in Jerusalem with his wife, Ronit, a doctor of biology. The two have seven children, including journalist Yair Sharki; in 2015, their son Shalom Yochai was murdered in a vehicular terrorist attack on Holocaust Remembrance Day evening.

For many years, he has served as a lecturer at Machon Meir and as rabbi of the “Beit Yehuda” community in the Kiryat Moshe neighborhood. In the past, he also delivered lessons at the Technion in Haifa. To my question why he didn’t turn to an academic career, which might have suited his broad horizons and research inclination, he responds: “In academia, I would have wasted time on formats, bibliography, and submission deadlines. I’m an autodidact, studying subjects that interest me. This perhaps leaves areas I haven’t touched, but internal freedom is more important to me. And besides, I’m convinced I would have had less influence.” When I ask what brought him to the rabbinate, he smiles: “In those days, I deliberated whether to be a gardener. What tipped the scale? The feeling that they need me.”

Democracy in danger

On the eve of the war, amid the storms surrounding the judicial reform, Rabbi Cherki was among the prominent rabbinical voices in support of the government. Among other things, he signed a public letter calling on state leaders to “continue your important mission” to fix the judicial system.

Q: You’re perceived as a rabbi who knows the secular public and might fill a bridging role, but you chose to align with the right camp’s simple messages.

“I didn’t align with the right, I aligned with democracy. Since Aharon Barak’s constitutional revolution, Israeli democracy has been in danger. The problem is that today, when they say ‘democracy,’ they illegitimately attach the term ‘liberal’ to it. Had the reform passed, perhaps we would have moved away from democracy in its liberal format, but not ceased being a democracy. The opposite is true. In politics, there’s room for dialogue and compromise, but on fundamental questions like the structure of democracy and the functioning of the High Court, decisions are required. Therefore, I supported the reform throughout.”

Q: Can you understand why they expected a different position from you?

“Certainly, after all, we’re educated toward inclusion and synthesis between sectors, things I’ve also taught for years. But this time it was clear to me that we’re in real danger. We’re already forgetting this, but before the war, there were intentions by powerful elements to carry out a coup, maybe even militarily. Therefore, it was necessary to stand firm and support the reform. After a decision had been reached in the political arena, there was definitely room for reconciliation and dialogue with opponents. Unfortunately, during the reform period, I observed that the left could not listen, while our public did. Nevertheless, we must be careful not to slide into excessive aggressiveness toward one group or another in the nation.”

Q: Ultimately, the move failed. Is there room for public soul-searching?

“The political move could have been done without unnecessary declarations. However, we need to understand that reform opponents didn’t take to the streets because of an incautious statement in the Knesset. This was an entire apparatus. What happened here is part of a global phenomenon in which jurists continuously undermine governments’ sovereignty. In my view, this involves a historical pendulum with implications for human and regime conception, as well as the courts’ place vis-à-vis elected institutions. Jordan Peterson warns about a similar struggle in Canada, and this has manifestations in Europe as well.

“It’s important for me to note that despite the media polarizing discourse, something in the public atmosphere has changed since the war. Perhaps I’m still one of those who practice the art of calm discourse through listening. I recently met with the French-Jewish philosopher Alain Finkielkraut, and we spoke for two and a half hours. He portrayed me incorrectly in media coverage, so I responded to him, and now he’s interested in meeting me again. That’s how dialogue works.”

Q: During the disengagement from Gaza, you supported refusing orders. How is this different from the refusal calls by “Brothers in Arms”?

“During the disengagement, no one intended to dismantle the army or state. They told Rabbi Avrum Shapira, who supported refusal, ‘This will dismantle the army.’ He replied, ‘It won’t, because there’s no such intention from the refusers or generally from our public.’ So the context of the term ‘refusal’ is completely different. According to Jewish law, if my father, whom I’m obligated to honor from the Torah, tells me to violate a rabbinical prohibition, I don’t listen to him, yet I’m still obligated to honor him. Similarly, in a democratic state, there’s room for civil disobedience driven by conscience. The problem with ‘Brothers in Arms’ is that they’re not willing to accept democratic game rules. This was using force to dismantle the state, and this is fundamentally different from what stood behind my call for refusal during the Disengagement period.”

In Rabbi Cherki’s view, one of the disengagement’s fundamental lessons is that Religious Zionism needs to aspire to state leadership. “The moment you say ‘I only need a study hall,’ – then you’re given a study hall, but don’t interfere in the state. This was a position adopted by part of the settlers’ leadership, and therefore, they were easy prey. We needed to aspire to state leadership, not settle for the religious affairs or education ministries.” In the two decades that passed since, he gets the impression, this lesson has already been largely internalized: “Any sociological look shows that Religious Zionism is destined to lead the state. This knowledge today frightens mainly the religious-nationalists themselves, but that’s the nature of things – whoever enters a leadership position must also grow culturally and spiritually, and I’m definitely willing to help him with that.”

Demonstrations against ultra-Orthodox draft at Jerusalem’s recruitment office on August 5, 2024 (Photo: KOKO)

Five months ago, Rabbi Cherki spoke during a rally at Hostages Square. “I spoke there against Hamas, and also spoke about the fact that no one has a monopoly on opinion regarding the hostages. I told them to present me as a cross-sector figure, and that’s how I also behaved in the speech.” In his view, this involves “a struggle between two values, the collective’s value and the individual’s value. Both are important, and each side of the dispute emphasizes one over the other. Our work is knowing how to connect these two concerns harmoniously.”

Q: Beyond principled harmony, what do you think should be done practically?

“It’s clear that what should stand before our eyes first of all is the general mission, which is victory over Hamas. This isn’t only our existential need; it determines the fate of relations between Islam and the free world. This is the war’s first mission, and the hostages issue mustn’t paralyze Israel’s ability to win.”

Q: Many justify their support for a hostage deal specifically in the name of the Jewish value of mutual responsibility.

“Jewish morality says to fight for hostages. You don’t negotiate with murderers.”

Not afraid of the world

Rabbi Cherki is among the few voices that emerged from Mercaz HaRav yeshiva and succeeded in breaking out beyond the yeshiva world to become a familiar voice in broad Israeli discourse. Unlike many of his generation, who operated mainly within the internal circle that formed over the years and advocated building a buffer against contemporary culture and thought, Sharki chose to expand his circles of influence into public discourse; he frequently appears in academic and cultural forums and participates in panels and open discussions. His love of dialogue with opposing views is also evident in the debate program “The Rabbi and the Professor” with Prof. Carlo Strenger, as well as in the “Israeli Issue” program, where he hosts various figures.

“I see myself as a student of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda, who gave enormous trust to the generation and never despaired of it,” Rabbi Sharki states. “Today, many portray Rabbi Zvi Yehuda’s character as stern-faced, strict in Jewish law, and so forth. This is exactly the opposite of what we absorbed from him. I remember one Saturday at his place, how in the middle of the meal, three young people entered – two boys and a girl. The rabbi received them with a smile, asked one of them if he had already fixed the car’s carburetor, the second about his tennis submissions, and the girl about her relationship with her boyfriend. No sermon, no rebuke; he dripped warmth and love. This was the Rabbi Zvi Yehuda we knew. From this position, he also went out to struggle when necessary.”

Q: Nevertheless, you’re somewhat exceptional among your generation’s peers who studied at “Mercaz HaRav.” You succeeded in developing a language that’s also accepted outside the yeshiva world.

“When the founding leadership of a certain group disappears, the next generation tends to entrench and see a threat in everything outside. Over time, a feeling of fear and isolation is created. Once they made a table on the internet of Religious Zionist rabbis and marked for each one which sector he belongs to – ‘lite,’ ‘Hardalite’ and such. They wrote me in an empty column because they didn’t know where to place me. In my view, a person should be faithful first of all to himself and his thoughts. So yes, I received a good education. On the other hand, I’m not an anarchist, and I recognize hierarchy and authorities. Therefore, I consider myself a distinguished student of Rabbi Zvi Tau, even if I am sometimes required to express a different position. This is Torah’s way.”

Q: Where is your main disagreement with Rabbi Tau?

“I contain all the streams – and ‘HaKav’ [The Line] also has a role,” Rabbi Cherki smiles. “I approach general culture from confidence and broad-mindedness, not from fear of foreign influences and not from desire to control it, but from understanding that this is the Holy One’s world, and we have a meaningful role in it. If you refuse to recognize value in truth points among your opponents, you don’t weaken them, but rather strengthen the counter-reaction.

“The last generation’s developments caused some to adopt the ultra-Orthodox criticism of society. In this criticism, there are valid points, and that’s also its problem: when the claim is completely wrong, it’s easy to reject it, but when there’s a kernel of truth in it, it’s much harder to deal with. Take, for example, a common ultra-Orthodox claim, that Zionism was intended to ‘convert the Jewish people from its religion.’ Indeed, among some Zionist activists, this was the intention. But HaRav Kook joined Zionism because he saw in it a movement greater than its activists. Ultimately, it’s a matter of where you stand within the great puzzle of the redemption process. Some say, ‘secular Zionism finished its role, we need to draw inspiration from the ultra-Orthodox.’ I’m not there.”

Q: How do you see the difference vis-à-vis the ultra-Orthodox world beyond the recruitment question?

“The ultra-Orthodox position sees Judaism as a religion; therefore, its emphasis is on preserving religious assets – yeshivot, study halls, Sabbath. The person is measured by their faithfulness to religion. The problem is that this thinking has also permeated us; I’ve already heard rabbis who studied at ‘Mercaz HaRav’ talking about ‘the Jewish people being born at Mount Sinai,’ and forgot it was already born at the Exodus from Egypt. Our basis is national, and it was on this basis that the Torah was built with its religious dimension. I’m aware that this is a message that may be difficult to contain, and therefore, it’s sometimes forgotten. When the ultra-Orthodox group chooses isolation as an ideal, it becomes less relevant to the world and also to the Torah itself, which is intended to change reality and not flee from it.

“The ultra-Orthodox now say that even those who don’t study Torah shouldn’t be drafted. I say the opposite: specifically, those who study seriously – they should be drafted. Torah study isn’t a reason to evade, but a source for taking responsibility. Even Moses, our teacher, went out to several wars in his life.”

Nevertheless, Rabbi Cherki expresses optimism regarding the ultra-Orthodox public. “The ultra-Orthodox have a role as a brake in Israeli society. Take, for example, the attitude toward the progressive movement. They’re not blind; they see well the dangers of family breakdown. They won’t swallow any nonsense in this context. What I predict is that, de facto, they’re already becoming Zionist. Their participation in state systems is expanding – in technology, academia, and economics. What primarily stops the process is the crisis surrounding recruitment. Therefore, I’m not worried about their population growth, because ultra-Orthodox ideology is becoming less relevant. In the end, a gap will be created between the ultra-Orthodox public and the ideology that has accompanied it for two hundred years, and then the ultra-Orthodox public will turn to HaRav Kook.”

Crossing the barriers of lies

A central and unique aspect of Rabbi Cherki’s activity is spreading Judaism’s universal message worldwide and promoting the Seven Noahide Laws within the framework of the “Brit Olam” [World Covenant] organization he founded. “We operate in North and South America, in the Far East, also a bit in Africa,” he says with satisfaction. This Tuesday, the organization will hold a festive event at the Ramada Hotel in Jerusalem, with the participation of students and supporters.

Rabbi Sharki’s perspective on this matter is grounded in several central sources of inspiration. Already in his youth, he was exposed to the writings of Rabbi Eliyahu Benamozegh, a Jewish-Italian thinker of the 19th century, who saw Judaism’s universal message as key to repairing the world. Later he also became acquainted with the thought of Rabbi Dr. Abraham Levine, a French intellectual who converted and was absorbed into Mercaz HaRav circles, and was close to Rabbi Cherki’s parents’ family; his book, “The Return of Zion as a Sign to Nations,” was translated from French by Sharki himself, and recently was published in a more popular edition under the name “The Hebrew Secret.” His great teacher, Manitou, also told him at the end of his days that “the next stage in redemption will be Torah for non-Jews.” In Rabbi Cherki’s view, “the Jews are the backbone of history, from the days of civilization’s beginnings in Sumer until our days.”

Q: Does the war harm your efforts?

“Interest in the State of Israel crosses the barriers of media lies. The people who come to us are characterized by intellectual independence. They’re capable of feeling that their original religion deceived them, so certainly they can identify this in the media.”

Q: When you speak to the world, you speak as a religious person, without the national element. Why?

“The Israeli nation is the only one whose nationalism isn’t expanded egoism. Our destiny is to be a blessing to all families of the earth, without demanding they be like us. Today, the world can absorb our message primarily through religion and individual lifestyle, but in a broader view, the political dimension must also be considered: the Seven Noahide Laws conclude with a commandment to establish courts, and only states are capable of fulfilling this. Ultimately, nations too will be forced to adopt this message. Therefore, I look with hope at people like Argentina’s President Javier Milei, who happily received the ‘Shulchan Aruch for Noahides’ I wrote and was translated into Spanish.”

Rabbi Oury Cherki (Photo: Naama Stern)

Q: Does this connect in your view to the geopolitical situation?

“Certainly. Jewish morality is built on the principle of unity of traits – combining kindness and judgment, compassion and justice. This is a revolutionary message in light of the rift between two worlds: the West, heir to Christianity, which established compassion as the sole moral value, and Islam, which mainly emphasizes the trait of judgment. This polarity produces continuous conflict that has no solution, unless they learn from us how to connect the traits. The world is shocked by an image of a child in Gaza, but ignores the justice of our struggle. This one-sided view produces imbalance; Judaism offers the key to a combination that balances between values.

“The question is what stands at the center of existence – God or man. Greek philosophy placed humanity at the center, while religions placed God at the center. In Judaism, by contrast, neither this nor that stands alone, but the dialogue between them. The idea that we’re partners in the act of creation is a universal idea that has a message for the entire world. Israel can constitute a model of a nation that offers a model of balance and partnership between man and God.”

Q: Over the years, you’ve referred to failures of Israeli public relations. What’s the message we need to convey to the world today?

“The people of the Bible return to their land. The notion that hiding our identity will bring us something is flawed. On the contrary, the moment we diminish ourselves to find favor, we lose our selfhood. Therefore, we shouldn’t fear the concept of ‘chosen people’ either. Levinas said this is the basis for tolerance. If I’m chosen, it means I serve, give something of mine, and also learn to receive. There’s no superiority and coercion here, but mutuality and openness. This is a concept that should be said with pride. When Netanyahu spoke in Congress, the message was clear: we’re on the front of the battle between good and evil, for the entire free world. The ‘chosen people’ idea was there, even if not explicitly.”

The interfaith dialogue Rabbi Cherki conducts also includes Islam. About a year and a half ago, he published a letter to Muslim religious scholars under the title “Bridge of Faith: What Judaism Thinks About Islam,” in which he proposed a framework for mutual recognition between religions as a basis for partnership among the children of Abraham.

“Islam is in acute crisis,” Sharki determines and explains that in the past, mainly until the 12th century, the mechanism of “ijtihad” existed in Islam – independent interpretation and legal renewal. “This is something reminiscent of the Oral Torah among us, with demand and ability to renew. However, at some point, it ceased, and Muslim law became fossilized. Recently, I met with senior state officials in Abu Dhabi, and they informed me that this was a mistake, and they’re now considering reopening it. Here, they have much to learn from us; among us, the Oral Torah enterprise never stopped. In the past, Muslim sages asked Jews how they deal with the Torah commandment to wipe out Amalek, and they answered, ‘Sennacherib came and mixed the nations.’ The Muslims saw in this a creative solution that could be theoretically accepted among them as well.

“The central point that needs to be understood in our discourse with the Muslim world is that Islam appeared about five hundred years after the Temple’s destruction, long after there was no longer a Jewish state. Therefore, the image of ‘Banu Israel,’ the children of Israel, is perceived in their eyes as a revered biblical-mythological entity, versus the ‘Yahud,’ the Jews of their time, which is perceived as a derogatory term. Now, as we return to our land, we must say simply: we are ‘children of Israel.’ This resonates deeply in Muslim consciousness, and repositions us as a dialogue partner God wants. In practice we can recognize Islam as a legitimate religion, but three conditions are required: recognition that Judaism wasn’t canceled in Muhammad’s prophecy but exists alongside it; abandonment of the ‘tahrif’ claim according to which the Torah was forged; and recognition of the Jewish people’s divine destiny to return to its land and rule it – as also mentioned in the Quran.”

Q: What about Muhammad’s character, where some of the foundational stories about him served as inspiration for terror organizations, from Hamas to ISIS?

“Maimonides devoted an entire chapter in ‘Eight Chapters’ to show that Moses our teacher sinned. The goal is to say that no prophet is exempt from criticism. In Islam, by contrast, Muhammad and all other prophets are presented as flawless. Here, it’s important to know that many stories about him aren’t found in the Quran but in hadith and traditional literature around him. If they accept only the Quran as authority, and everything else will be cast in doubt – there’s an opening for rapprochement here.”

The post 'Jews are the backbone of history' appeared first on www.israelhayom.com.