He dressed the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Katharine Hepburn and Bette Davis, but while Australian-born costume designer Orry-Kelly is one of the country’s most prolific Oscar winners, many people have never heard of him.

Born Orry George Kelly in Kiama on the south coast of NSW in December 1897, the Hollywood costume designer worked on more than 300 films.

He was the chief costume designer for Warner Bros. Studios from 1932 to 1944, worked on the iconic film Casablanca and won Oscars for Best Costume Design for An American in Paris in 1951, Les Girls in 1957 and Some Like It Hot in 1959.

An American in Paris was produced in 1951, winning Orry-Kelly his first Oscar for best costume design. (Supplied: Metro-Goldwyn Mayer)

Orry-Kelly received an Oscar for best costume design for Les Girls in 1957. (Supplied: Metro-Goldwyn Mayer)

Following his death in 1964, Orry-Kelly was mourned by Hollywood society but Australia remained largely oblivious to his remarkable life.

His pallbearers included actors Cary Grant (who Orry-Kelly described in his memoir as having a lifelong relationship with) and Tony Curtis, filmmaker Billy Wilder and director George Cukor.

“There were obituaries in Time, Newsweek, Variety, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Herald Examiner, but nothing in the Sydney Morning Herald,” historian Sue Eggins said.

Ms Eggins said while Kelly was still “the forgotten man”, an exhibition and gala in his home town of Kiama later this month aimed to change that.

Orry-Kelly’s last Oscar was awarded for best costume design in Some Like It Hot in 1959. (Supplied: Mirisch Company)

Rediscovering Orry-Kelly

Ms Eggins is president of the Kiama Historical Society and a member of Kiama Icons and Artists, which promotes local art and culture.

She said Orry-Kelly was largely forgotten locally until a 1994 Vogue article by Karin Upton Baker, edited by filmmaker Baz Luhrmann and Catherine Martin, winner of four Academy Awards in film design.

Sue Eggins holds a photograph of a young Orry-Kelly. The costume designer grew up in seaside Kiama. (ABC Illawarra: Sarah Moss)

“It had photos and stories, and since then I’ve discovered more and given hundreds of talks about him.

“I love him. I’m passionate about him,” she laughed.

Tailor’s son becomes couture designer

Orry-Kelly started painting portraits at a very young age. (Supplied: Catherine Menzies)

Orry-Kelly’s work displayed a diligence and creativity he no doubt inherited from his father William Kelly, a tailor in Kiama.

Mr Kelly put his son’s talents to use by having him paint portraits of his customers.

“Clients got a new suit and a painting, so there are a lot of portraits around the district,” Ms Eggins said.

When he was 17, Orry-Kelly was sent to Sydney to study banking, however Ms Eggins said he ended up being paid by women to take them dancing.

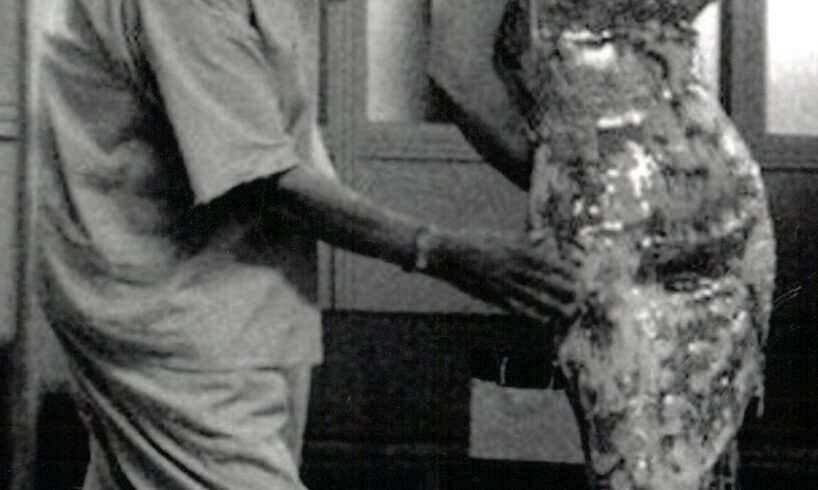

in 1934 Warner Bros. produced behind-the-scenes photographs of Orry-Kelly at work. (Supplied: Catherine Menzies)

“He was a very good dancer and got caught up in the underworld of Sydney, the sly grog and all of that,” she said.

“In his autobiography, he remembers what the prostitutes in Sydney were wearing and they became inspirations for some of his costumes.

“I don’t think the Hollywood actresses would have been pleased knowing their costume was copied off a Sydney prostitute.”

Orry-Kelly moved to New York at 22, where he met a young actor who would later change his name to Cary Grant.

The pair relocated to Los Angles in 1931 where both their careers took off.

In 1938, Orry-Kelly’s work was highlighted in American Vogue magazine. (Supplied: Vogue)

Deadly, extravagant lifestyle

Orry-Kelly worked on silent films at first, becoming the chief designer for Warner Bros. in 1932.

“By 1941 he was earning $750 a week, which was a lot of money,” Ms Eggins said.

“He drank it, he partied, he bought a big house, he had pets and generally wasted a lot of it.

“He was a very big drinker, an alcoholic and that’s where a lot of his money went.”

By 1944 Orry-Kelly worked for 20th Century Fox, then Universal until 1950, followed by freelancing until he died of live cancer, aged 66, in 1964.

Orry-Kelly fitting Marilyn Monroe for Some Like It Hot in 1959. (Supplied: Catherine Menzies)

Missing Oscars

When he died, Orry-Kelly’s three Oscars went to movie tycoon Jack Warner’s wife Anne but have since vanished.

“We are looking for the Oscars,” Ms Eggins said.

“In 2015 the Oscars were in Ann Warner’s box, then they were borrowed by the Australian Centre for the Moving Image [ACMI] who displayed them, but said they sent them back.”

Orry-Kelly accepting his Oscar for An American In Paris in 1951. (Supplied: Catherine Menzies)

“At that time, Film and Sound Archives [the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia or NFSA] in Canberra were trying to get the Oscars to stay in Australia, but as far as I know, they didn’t,” she said.

“We think they’ve gone back to the storerooms at Warner Bros.”

The ABC contacted ACMI, the NFSA and Warner Bros. Discovery; none could clarify the Oscars’ whereabouts.

Orry-Kelly’s Oscars were last seen in public in a purpose-built display cabinet at ACMI in Melbourne in 2015. (Supplied: Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI))

Gala, glamour and gowns

An event celebrating the costumer designer, the Orry-Kelly Dressing Hollywood Gala, will be held in Kiama on July 26.

“We’ll display original paintings and gowns with a gala that evening,” the event’s organiser Catherine Menzies said.

Catherine Menzies at a cottage once occupied by Orry-Kelly’s parents in Kiama. (ABC Illawarra: Sarah Moss)

A Q&A panel will feature Gillian Armstrong, who directed the 2015 documentary Women He’s Undressed about Orry-Kelly’s life, as well as the film’s producer Damien Parer and screenwriter Katherine Thomson, who discovered Orry-Kelly’s manuscript, which was published as an autobiography and later inspired the film.

Ms Menzies said the aim is for the gala to become an annual event.

“Hopefully it can become a thing for Kiama; what better way to honour somebody like Orry-Kelly than glamour,” she said.

“He was making people look good [and] feel good. I can’t think of a better way to have fun, but honour him.”

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image held a retrospective exhibition for Orry-Kelly in 2015. (Supplied: Mark Gambin)