The US military’s recent strikes on boats allegedly transporting drugs near the Venezuelan coast have raised questions about the legality of such actions and heightened fears of a military escalation in the region.

In the latest attack on Friday, at least four people were killed, taking the death toll to 21 since the first boat was attacked on September 3 as part of the Trump administration’s “war on cartels”.

US President Donald Trump has declared drug cartels to be unlawful combatants and determined that the United States is in “a non-international armed conflict” with them, the administration notified Congress on Thursday.

But critics argue that the administration’s military actions potentially violate the US Constitution in addition to international laws, with rights observers and legal scholars saying the deadly attacks amount to “extrajudicial killing” and violation of human rights.

Since taking office in January, Trump has designated several drug cartels, including the Tren de Aragua cartel based in Venezuela, as “global terrorist organisations”.

In the past several weeks, the Trump administration has deployed warships in the Caribbean to target boats that it says are involved in “narco-trafficking”, ratcheting up military and political pressure against Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro, who has condemned the “US aggression” against his country.

So are Trump’s strikes legal, and will they lead to military confrontation with Venezuela? And what is the history of Venezuela-US tensions?

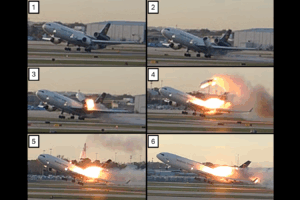

A vessel burns in this still image taken from a video released September 15, 2025, depicting what US President Donald Trump said was a US military strike on a Venezuelan drug cartel vessel that had been on its way to the US, the second such strike carried out against a suspected drug boat in recent weeks [Handout/Donald Trump/Truth Social/via Reuters]

What we know so far

The US has carried out at least four strikes in recent weeks on small vessels in the Caribbean Sea, near Venezuelan waters, that Washington claims were carrying illegal drugs.

The most recent strike, on Friday, destroyed a vessel that was accused of carrying narcotics. Two other strikes last month killed at least six people. At least 11 people were killed in the first strike on September 3.

The Pentagon, however, has not disclosed precise locations or evidence linking the targeted boats to drug-trafficking networks. Washington has not provided any proof of its claims about the boats carrying drugs.

US officials say the operations were conducted in international waters, while Venezuelan authorities insist they occurred dangerously close to, or inside, the country’s territorial zone.

What has Trump said?

Speaking at Naval Station Norfolk on Sunday, Trump applauded the US Navy’s efforts to combat “cartel terrorists”, noting that another vessel off Venezuela’s coast had been hit on Saturday.

Trump also postured for further action inside Venezuelan territory. “In recent weeks, the navy has supported our mission to blow the cartel terrorists the hell out of the water … we did another one last night. Now we just can’t find any,” he said.

“They’re not coming in by sea anymore, so now we’ll have to start looking about the land because they’ll be forced to go by land,” Trump added.

Later, speaking with the reporters at the White House, the US president noted that the US military build-up in the Caribbean had halted drug trafficking from South America. “There’s no drugs coming into the water. And we’ll look at what phase two is,” he said.

Al Jazeera, however, could not independently verify Trump’s claims.

Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro says the US deployments were ‘the greatest threat that has been seen on our continent in the last 100 years’ [File: Leonardo Fernandez Viloria/Reuters]

How has Maduro responded?

Venezuelan leader Maduro, who has called the strikes “heinous crimes”, has said that he is prepared to declare a state of emergency in the event of a US military attack amid a large US military build-up in the southern Caribbean.

The US has deployed at least eight warships and one submarine to the eastern Caribbean as well as F-35 aircraft to Puerto Rico, bringing thousands of sailors and marines to the region, reported Reuters.

In August, the US doubled its existing bounty on Maduro to $50m and accused the Venezuelan leader of being one of the world’s leading narco traffickers and working with cartels to flood the US with fentanyl-laced cocaine.

In a televised address last Monday, Maduro announced that a “consultation process” had begun to invoke what he called a “state of external unrest” under the Constitution of Venezuela, aimed at protecting the people.

Maduro has repeatedly claimed that the Trump administration wants to overthrow his government – an allegation that Trump has denied, saying, “We’re not talking about that.”

Venezuela’s Vice President Delcy Rodriguez said that the emergency declaration would grant Maduro special powers to mobilise the armed forces and close Venezuela’s borders if needed.

She said the measure was intended to defend the nation’s sovereignty and territorial integrity against “any serious violation or external aggression”.

Caracas has staged military drills, mobilised militias, and postured its Russian-made fighter jets under a “defence of the nation” campaign.

Are US strikes legal?

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has said the maritime strikes amount to “extrajudicial killings”.

“US officials cannot summarily kill people they accuse of smuggling drugs,” said Sarah Yager, Washington director at HRW. “The problem of narcotics entering the United States is not an armed conflict, and US officials cannot circumvent their human rights obligations by pretending otherwise.”

Salvador Santino Regilme, a political scientist who leads the International Relations programme at Leiden University, said that under Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter, the use of force by one state against another is prohibited except when authorised by the UN Security Council or exercised in legitimate self-defence under Article 51.

And the US claim that strikes against “drug traffickers” near Venezuela amount to self-defence “appears legally untenable”, Regilme told Al Jazeera.

He noted that drug trafficking, even when transnational, does not constitute an “armed attack” under customary international law.

“Unless Washington can prove that the targeted actors carried out or imminently threatened a large-scale armed attack attributable to Venezuela, these actions risk violating the charter’s core prohibition on the use of force and undermining another state’s territorial integrity,” Regilme said.

To qualify as a non-international armed conflict, as the Trump administration notified Congress, said Regilme, there must be protracted armed violence between organised armed groups or between such groups and a state under the Geneva Conventions. Simply labelling cartels as “terrorists” or “narco-terrorists” does not automatically trigger the applicability of international humanitarian law (IHL), he added.

Expanding the “terrorist” label to justify military targeting risks normalising warlike responses to what are primarily criminal and socioeconomic problems,” Regilme said, referring to the US strikes.

“It militarises law enforcement and blurs the boundaries between crime control and warfare, which has led to severe human rights abuses in the so-called ‘war on drugs,’ from Mexico to the Philippines,” he told Al Jazeera.

Celeste Kmiotek, a senior staff lawyer at the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based think tank, said in a report that even outside armed conflict, striking a vessel without imminent threat or judicial process may constitute an arbitrary deprivation of life.

Domestically, lethal targeting abroad requires a clear legal basis under US statutes or the US Constitution, she said, adding that no congressional consent or specific Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) covers anti-drug operations in Venezuela.

How have other countries reacted to this?

Several Latin American countries have criticised the actions, with Colombia’s leftist President Gustavo Petro calling the strikes an “act of tyranny” in an interview with the BBC.

“Why launch a missile if you could simply stop the boat and arrest the crew? That’s what one would call murder,” he said.

Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has also condemned the US attacks on boats, which he said amount to “executing people without a judgement”.

“Using lethal force in situations that do not constitute armed conflicts amounts to executing people without a judgement,” President Lula said in a UN speech last month. He has also expressed his criticism against the deployment of US naval forces to the Caribbean, calling them a source of “tension”.

Russia has also condemned the US strikes.

“The ministers expressed serious concern about Washington’s escalating actions in the Caribbean Sea that are fraught with far-reaching consequences for the region,” the Russian Foreign Ministry said after a phone call between Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and his Venezuelan counterpart Yvan Gil.

China, one of Caracas’s largest trading partners, warned that US actions in waters off Venezuela pose a threat to “freedom of navigation”.

China “opposes use of threat [or] force in international relations [and] … any interference in Venezuela’s internal affairs on any pretext”, Foreign Ministry spokesman Guo Jiakun told reporters in Beijing.

“The unilateral enforcement actions by the US against foreign vessels in international waters, which exceed reasonable and necessary limits, violate international law, and infringe [on] fundamental human rights, such as right to life,” said Guo.

He added that these actions “pose a potential threat to the freedom and safety of navigation in relevant waters and may impede the freedom of high seas enjoyed by all countries in accordance with international law”.

Members of the National Bolivarian Militia gather after responding to Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro’s call to defend national sovereignty amid escalating tensions with the US, in Valencia, Venezuela on September 5, 2025 [Juan Carlos Hernandez/Reuters]

What does it mean for the US influence in the region?

The scope of accountability of the US strikes on vessels off the Venezuelan coasts is quite limited, said Regilme.

This episode reflects a recurring pattern in US foreign policy, which he termed “militarised punishment: the use of military force framed as moral enforcement rather than lawful defence”.

Instead of addressing the complex social and economic roots of drug trafficking, he said, Washington relies on coercive displays of power that project moral authority but lack a clear legal foundation.

Regionally, Regilme said that the strikes could exacerbate distrust toward US interventions in the Southern Hemisphere.

Latin American states, even US allies, remain deeply sceptical of Washington’s extraterritorial military actions justified under counter-narcotics or counter-terrorism rhetoric, he said, which stands to erode regional cooperation mechanisms and embolden nationalist or anti-imperialist political actors.

US ties with Venezuela deteriorated after the 1998 election of President Hugo Chavez, whose socialist agenda sought to reclaim national control over Venezuela’s vast oil wealth by increasing royalties on foreign firms and tightening state oversight.

Chavez also forged close alliances with Cuba, China, and later Iran, marking a sharp ideological break from decades of alignment with Washington.

Under Maduro, who succeeded Chavez in 2013, the bilateral tensions deepened amid Venezuela’s worsening economic collapse and growing authoritarianism.

Since Trump returned to the White House in January this year, the tensions have become worse.