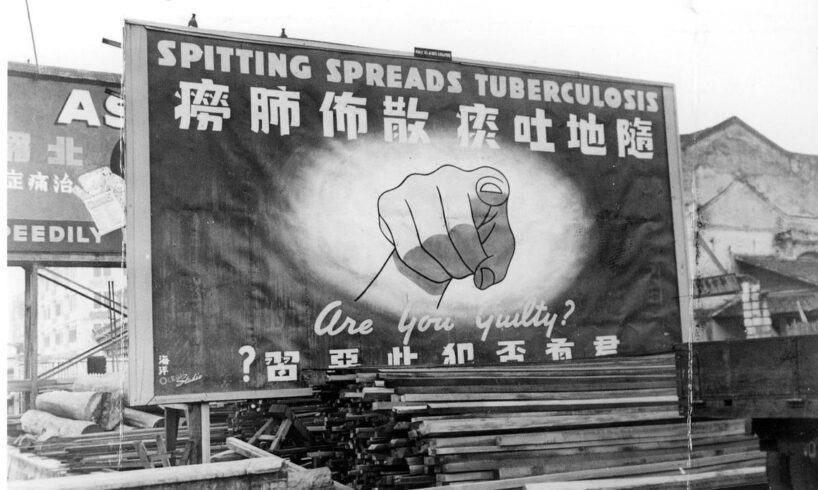

“No spitting campaign gets a big start,” declared a Page 1 article on Aug 2, 1958, the year before Singapore achieved self-governance.

Anti-spitting posters were put up, including at the City Council building, a rally was held to spread the message, and thousands of letters passing through post offices in Singapore were stamped with the words “Don’t Spit”.

Spitting – and its potential to spread disease – was a public health menace, and it had plagued Singapore for a long time.

Beyond reporting, The Straits Times has served as a platform for civic frustration and concern, with readers writing in regularly to express alarm at the poor hygiene of their fellow men. Reports over the decades also show that while the tools to fight bad habits have changed – from posters to urine detectors – the message has remained constant.

In 1925, a century ago, a reader wrote in to suggest that anti-spitting notices be displayed in government offices, trams, eating houses and other public places. “The spitting that goes on in our trams is positively dangerous,” said the reader, adding that a crackdown on spitting might help prevent the spread of tuberculosis.

The problem of keeping public places clean persisted beyond World War II, alongside worries about malnutrition in the population.

In 1947, a doctor wrote to the paper to note that spitting in the street and buses was far too common: “I have even shared a taxi with a man who occupied his time expectorating on the floor.”

A worker clearing up rubbish at the Padang after an anti-spitting rally and concert in 1958.

PHOTO: ST FILE

In 1949, the municipal commission of Singapore was reportedly considering imposing a stiff fine and even jail for those caught spitting. A reader wrote in to argue against such penalties, questioning if these would even make a dent in the problem, “when half of Singapore spits”.

Complaints about public cleanliness and disgusting habits like spitting and peeing in public cropped up from time to time even after Singapore gained independence in 1965 and became more developed.

In 1981, a reader wrote in after witnessing a bus driver, who had stopped at a traffic light, clearing his throat to spit out the window “nonchalantly” on the road.

Noting that it was a common habit, the writer added: “It is a disgusting and appalling habit and most unhygienic, to say the least. What if the spitter happens to be a carrier of tuberculosis or flu germs or who knows what other contagious diseases?”

In May 1984, another “Stop Spitting Campaign” was mounted by the Government to educate the public on the evils of spitting in public places.

As part of the campaign, the Registry of Vehicles took the no-spitting message to 40,000 public transport workers, with stickers, posters and advertising panels spreading the campaign slogan: “Stop That Spitting Habit – It’s Dirty. It Spreads Disease.”

A giant poster on the marble columns of the Singapore City Council on Aug 1, 1958, proclaiming the start of the council’s anti-spitting campaign. The poster is designed to convey, without words, the message “Do not spit”.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The act of spitting took on greater menace during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) epidemic and later the Covid-19 pandemic.

The authorities cracked down on spitting during the Sars epidemic in 2003.

In May that year, the National Environment Agency nabbed 31 people for spitting in public and made an example of 11 by charging them in court. Each offender was named and made to pay a fine of $300.

In June 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic, a woman was charged over hurling abuse and

spitting at an employee

in a KFC outlet. In April the same year, a man was jailed

for spitting on the floor

of a hotel lobby and shouting “corona, corona”.

Besides spitting, another nuisance in the 1970s and 1980s was urinating in lifts, when more Singaporeans started moving into high-rise public housing.

A resident of Block 18 Marine Terrace wrote to The Straits Times in 1977 to complain about how the three lifts in the block “are always full of urine”; in 1987, grassroots leaders in Telok Blangah launched a campaign against urinating in lifts by putting up posters and giving out pamphlets, after complaints about smelly lifts.

In January 1988, the Housing Board started installing urine detectors in some estates, the paper reported in a Feb 28, 1988, article headlined “More caught on film with their pants down”. A 79-year-old man in Tampines and two boys aged seven and nine in Ang Mo Kio were among those who were arrested.

The urine detectors could pick up on the salt content in urine, which would activate a video recording and stop the lift. The culprit would be freed by a lift rescue team and handed over to the police.

By 1997, the problem looked to be under control in HDB estates with the greater introduction of urine detectors, The Straits Times reported.

It was harder to eradicate it from other public places.

In 2008, a stink was raised about the stench of urine that hung over a walkway to the Esplanade; also causing olfactory offence were suspicious puddles in the stairwells of buildings like Lucky Plaza or Hong Lim Complex.

Urinating in public remains a nuisance.

In January 2025, three men were separately caught urinating at Outram Park, Potong Pasir and Tanah Merah MRT stations. The paper reported in the same month that an astonishing average of 600 people were fined each year for urinating or defecating in public from 2020 to 2024.

Ho Ai Li is assistant foreign editor at The Straits Times. She joined the paper in 2002 and has reported on both education and entertainment. A former foreign correspondent based in Taipei, then Beijing, she writes on pop culture, heritage and the history of Singapore.