Several times over the last five years, when Haley Bassett has turned on the taps at her family’s farm near Dawson Creek, nothing has come out. When she checks her well, the water filter is clogged with black sand.

It’s one of many strange changes she’s noticed around the property her grandparents began farming in the 1960s, as deep-seated drought takes hold of the region.

“Now, I just have huge piles of sand in my yard that was pumped out of my well,” she said.

Much of northeastern B.C. is in severe or extreme drought, which has dried up rivers, stressed reservoirs and forced local governments to restrict water use.

Bassets says crop yields are thinning, trees are dying prematurely and weeds like Canada thistle have exploded. Winter winds at times blow more dust instead of snow.

She worries about how much longer her well will hold out, and what’s being done to protect the water that feeds it.

“I’m bracing for the day I will have no water.”

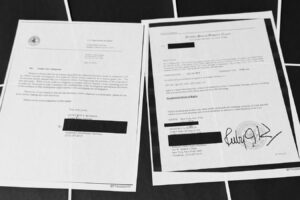

Haley Bassett says her water filter has been clogged with black sand numerous times over the last five years as deep-seated drought takes hold of northeastern B.C. (Submitted by Haley Bassett)

Advocates call for higher rates, stronger oversight

Her concerns are shared by advocacy groups that say provincial policy continues to undervalue its water resources as the province pushes to expand major projects, from mining to LNG to AI data centres.

“What they’re paying right now is horrendously low,” said Kiki Wood, a campaigner for Stand.earth, one of two environmental groups that have called on the province to increase industrial water rates in recent weeks.

At $2.25 per million litres, B.C.’s industrial water rate is the lowest in Canada, far below the $54 to $179 charged by other provinces, according to a recent report from the B.C. Watershed Security Coalition calling for the same change.

CBC News requested an interview with Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Randene Neill. Instead, Ministry of Energy and Climate Solutions Adrian Dix, speaking on behalf of the B.C. government, defended the province’s policies.

“Every licence is reviewed and controlled. Streamflow levels are very important,” Dix said. “That’s what the B.C. Energy Regulator does in every case. In other words, puts the environment and human health first.”

He said B.C.’s water management framework remains “the most rigorous” in North America, developed from scientific advice provided by an expert panel in 2018.

B.C. Minister of Energy Adrian Dix said the province’s industrial water policies for oil and gas companies are among ‘the most rigorous’ in North America, and based on scientific advice from a 2018 panel. (Dillon Hodgin/CBC)

Rising industrial use in northeast B.C.

The Watershed Security Coalition says B.C. industries are authorized to draw about 2.6 trillion litres of water annually, roughly equal to what 27 million people use in a year.

It adds that the province collects $400 million a year in water rental fees, “nearly all of this from hydropower generation.” It says raising rates in line with other provinces could generate an extra $100 million annually, money that could be reinvested in watershed protection.

“Surely there is a price that really puts the proper value on that resource,” said Wood. “Increasing provincial revenues for resources that industry is using feels really practical, really urgent and really smart.”

In the northeast, industry demand for water is on the rise.

Public filings from the B.C. Energy Regulator show withdrawals by oil and companies have increased sharply in recent years, from 3.6 million cubic metres (3.6 billion litres) in 2017 to just over nine million cubic metres (9 billion litres) in 2024.

Roughly half that water went to fracking, with the rest used for pipeline commissioning, dust control, equipment washing and other work “where much of the water is returned to the water cycle,” the regulator said.

Water levels along the Kiskatinaw River, seen here this fall, are at historical lows amid a drought across northeastern B.C. (Donald Hoffmann)

Withdrawals are routinely suspended during droughts, including on the Kiskatinaw River, where restrictions have been in place since spring 2023, the regulator said, adding that about 68 per cent of water used for fracking in B.C. is now reused wastewater.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers echoed those figures.

“These efforts are particularly important given the region’s sensitivity to drought and the need to balance industrial, environmental and community water needs,” said Richard Wong, the association’s vice-president of regulatory and operations.

‘Deeply exploitative’

But Bassett isn’t reassured.

“There’s what they say and then there’s what we’re experiencing and seeing with our own eyes, right?” she said. “And those things do not line up.”

She says nearby communities like Dawson Creek, which has declared a state of emergency and wants the province to fast-track a $100-million pipeline and new water supply, is proof of just how stretched local water supplies have become.

She believes industry should be paying more for water, especially as nearby communities face shortages.

“Why does industry need that kind of deal from us?” she said.

“I’m not seeing the return. The amount of money that is extracted from this region and what this community sees in return, it’s not right. It’s exploitative, deeply exploitative.”

Climate puts pressure on growth

Joseph Shea, an environment professor at the University of Northern British Columbia, said the Peace Region’s snowpack was only 76 per cent of normal this spring, and 65 per cent in 2024. Earlier melts and hotter, drier summers are leaving little moisture to recharge rivers or groundwater.

“It’s a really tough situation to get out of because you need to have a really good snowpack and then wet and cool summers repeatedly in order to reverse that drought,” Shea said. “Climate change is not making any of this easier.”

He said careful management will be crucial as the province pursues new economic projects. Raising industrial rates could encourage more conservation and fund better monitoring.

“There’s lots of questions and lots of gaps in what we actually understand about water across the province,” he said. “Understanding community water systems and the potential impacts and changes due to climate changes or increased demands on the water supply are going to become, I think, really big questions in the coming years.”

Government ‘asleep at the wheel’

Back on her farm, Bassett is bracing for another dry winter. She worries government and industry won’t act fast enough to protect the region’s water.

“It feels as though our government at every level has been asleep at the wheel and allowed this problem to reach this point,” she said.

“They’re just calling for more and more and more, and there is not enough water to sustain that amount of industry without completely leaving communities out in the cold.”

WATCH | B.C. unveils new drought-tracking system:

B.C. unveils new drought-tracking system

As the driest summer months approach, the B.C. government has unveiled a new system to track and report drought conditions in the province. The program will show how much water a community has stored for use and how well rivers and creeks are flowing.

Source