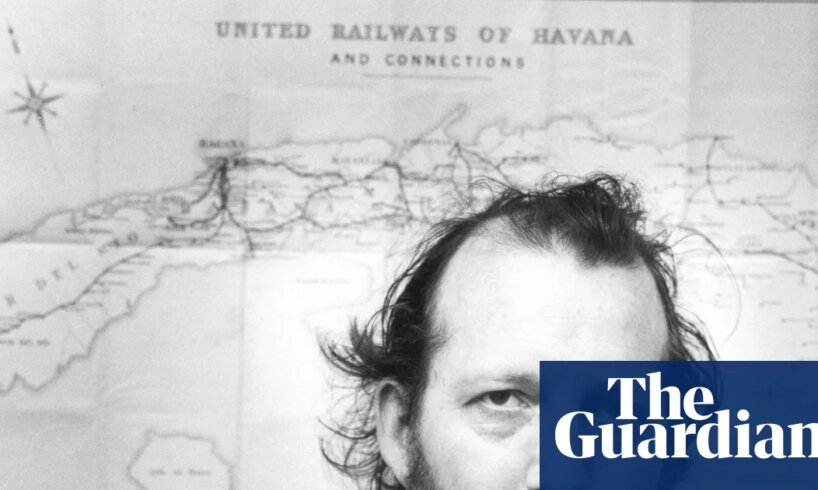

After the Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara was executed in October 1967, his body was placed on display to the press by the US-supported Bolivian army in the remote town of Vallegrande. The event was watched over by a CIA agent, who in turn was watched by Richard Gott, the Guardian journalist, who has died aged 87.

The head of the CIA’s “country team” was furious at being spotted by Gott, who also confirmed that it was Guevara’s body. Apart possibly from the agent, he was the only person there who had seen Che before.

Guevara’s death, Gott would write in his authoritative Cuba: A New History (2004), ended many people’s romantic association with the Cuban revolution, but he held “an abiding affection for the people and their struggle …” His sympathy for that struggle and against regional imperialism from the conquistadores to the norteamericanos, became a lifetime focus.

Gott’s early career wandered in several directions. Perhaps our generation (I was a close friend of his from college years onwards), living under the threat of mutual assured destruction, placed little value on a “career” anyhow.

His first published work was as a historian of prewar appeasement. He might have become London region organiser for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament if he had not been offered a research post at the international affairs thinktank Chatham House. In 1965 he became a leader writer on European affairs at the Guardian, but took leave to stand as an anti-war candidate (for the short-lived Radical Alliance) in the 1966 Hull North byelection.

He was not ideologically versed – he would have been bored with a debate on the “transition to socialism” – and his approach led to an engaging but sometimes disconcerting eclecticism of attitude and belief.

Everyone found him a delightful person to talk to even when they disagreed: a Latin American ambassador would sum this up. “Richard has the unique ability,” he said, “to charm and to appal members of the establishment at one and the same time.”

As Gott’s election agent in Hull, I observed how the candidate could fluently “charm” sceptical journalists. Interest was intense because, since the Wilson government had a majority of only one, a Labour defeat in a marginal might precipitate a general election.

The Vietnam war, Gott wrote, was “one of the great crimes of the century”, and a stand had to be made. Domestic policy played little part in his manifesto, though he argued that defence spending made it impossible to finance vital infrastructure projects such as the Humber bridge, which Hull had long desired. Wilson sent his transport minister Barbara Castle to “[tell] them categorically they would have their bridge”. The voters were less interested in Vietnam and Gott received a total of 253 votes, but Hull got the bridge.

Gott was born in Aston Tirrold in the Berkshire Downs, the son of Mary (nee Moon), a teacher, and Arthur Gott, an architect. His parents were not politically active but would support him later: a family anecdote relates how his mother tried to register a racehorse with the name “Ban the Bomb”, so that punters might shout it out as the horse came down the straight. The Jockey Club rejected her request.

From 1952 to 1957, Gott attended Winchester college, the public school where he acquired the air of self-confidence often associated with Wykehamists. He won an exhibition to Corpus Christi College, Oxford (1958-61), and obtained a BA in modern history.

There he discovered a new world of protest, and became secretary of the national student campaign. When he and friends protested outside the Sheldonian at Harold Macmillan’s inauguration as chancellor, the proctors quickly intervened. Gott also found time to work with the historian Martin Gilbert on “the docs” – the records of prewar appeasement – which resulted in their well-received book The Appeasers (1963).

Soon after the Hull byelection, he left the Guardian to help his dynamic colleague from Chatham House, Claudio Véliz, set up an institute of international studies at the University of Chile.

His revolutionary engagement owed much to the development economist Ann Zammit, whom he married in 1966. He produced a comprehensive study, Guerrilla Movements in Latin America (1970); Ann, he wrote, “would have preferred me to join the guerrillas rather than to write about them”. They adopted a son, Inti, from Bolivia, and a daughter, Araucana, from Chile.

Leaving Chile, Gott had a brief spell in Tanzania, as foreign editor of the Standard, edited by the senior ANC figure Frene Ginwala. He was soon welcomed back to the Guardian, first as foreign correspondent in Latin America and then, under the new editor Peter Preston, as features editor (1978-89), then literary editor (1992-94). His choice of contributions in both departments were much admired, with decisions that were often brilliant and occasionally wilful.

His Guardian career came abruptly to an end in December 1994, in a revelation that was highly damaging to him and to the newspaper. The Spectator claimed that, according to a former KGB member, Gott had been controlled by the agency and was a paid informer for a number of years.

He promptly handed in his resignation to Preston, and the Guardian printed his hastily written explanation, which only made matters worse – Gott’s friends wished he had taken time and advice before responding.

He admitted having “enjoyed” contacts with Russian and other Soviet-bloc officials and having accepted Soviet-paid trips to Vienna, Athens and Nicosia. Fatally, he acknowledged taking “red gold, even if it was only in the form of expenses”. He had regarded it all as “an enjoyable joke”, in cloak-and-dagger fashion. Gott denied receiving direct payments or naming fellow journalists: he had been called in by MI6 almost a decade before and they had accepted his explanation.

With hostile media and politicians seizing on the affair, Gott’s manner of resignation made it more difficult to rebut the wilder allegations, which continue to this day. A broader issue remained undiscussed: was it legitimate for journalists to accept meals, freebies and more from “our” side, or indeed from some dubious regimes, but wrong from “theirs”? The fact remained that, as Gott admitted, he should have declared the contacts to Preston, whom he deeply regretted having let down.

However, he was not crushed. Gott not only recovered, with support from his second wife, Vivien Ashley (whom he married in 1985, his first marriage having ended in divorce), but went on to produce more significant work. (He had already published an evocative account of their travels together across the South American watershed, in Land Without Evil, 1993, perhaps his best book).

Increasingly, he saw Latin American history in terms of “settler colonialism” with the suppression of indigenous rights. The “left” regimes that he applauded, such as that of Hugo Chávez (In the Shadow of the Liberator, 2000), should be seen more as a reassertion of those rights. Bringing the argument closer to home, he compiled an account of British imperialism up to the 1860s, seeking to reveal “a history of systemic repression and almost continual violence” against indigenous peoples (Britain’s Empire, 2011).

In poor health in his final years, but quietly cheerful, he and Vivien enjoyed family life with numerous grandchildren, and entertained a wide range of friends who still believed that the world could be, or should be, a better place.

He is survived by Vivien, Inti and Araucana, six grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

Richard Willoughby Gott, historian and journalist, born 28 October 1938; died 2 November 2025