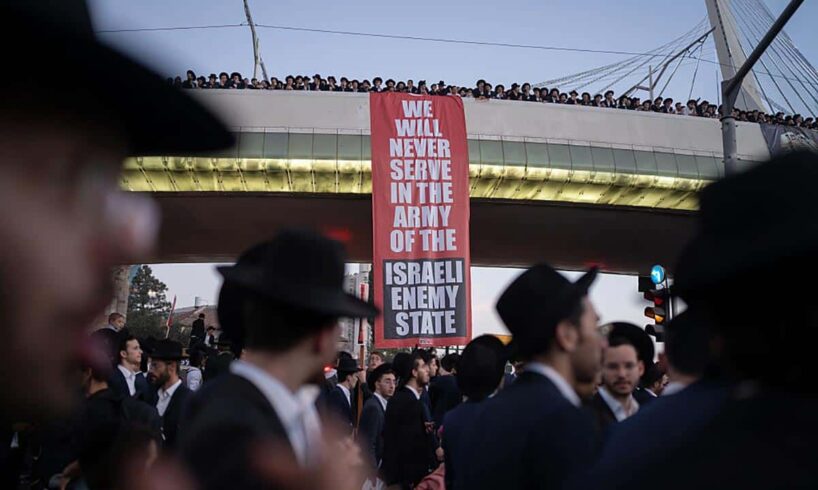

About 200,000 Haredim (ultra-Orthodox Jews) protested in Jerusalem against plans to require some Haredi young men to draft into the military on Thursday.

The protest took place as the Knesset prepared to discuss a new bill aimed at increasing recruitment among Haredim and addressing escalated tensions throughout Israeli society over the debate on how to handle the burden of service.

Who are the Haredim?

Haredim are ultra-Orthodox Jews who adhere to a strict approach to religious observance, often residing in relatively enclosed communities with varying levels of interaction with the rest of society.

The Haredi community is far from a monolith. The umbrella term encompasses a diverse range of factions, communities, and leaders, with varying opinions and practices among the different groups. The broadest division is between Ashkenazim, communities with roots in Eastern and Central Europe, and Sephardim/Mizrahim, communities with roots in Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East. Within those communities are further divisions, and within those divisions are even more divisions.

For example, Ashkenazim are primarily split into Hassidim — who tend to place a focus on Kabbalah, mysticism, and emotional connections to religion — and Litaim, who place more of a focus on intellectualism and distance themselves from mysticism to an extent. Not all Haredi communities fit neatly into these boxes, and within these boxes, there is a wide range of diverse communities.

Some Haredi communities don’t accept the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish state, while others do. There are two Haredi political parties in the Knesset: United Torah Judaism, which represents Ashkenazim, and Shas, which represents Sephardim and Mizrahim. These parties both have a council of rabbis who advise them on decision-making.

Haredi students study the Torah at the Ponevezh Yeshiva (Jewish Religious school) in the central Israeli city of Bnei Brak on February 27, 2024. As Israelis are called up to join the war effort in Gaza, anger is mounting at the Haredi community which has long been spared the compulsory military service required of most citizens. (Photo by Menahem Kahana / AFP via Getty Images)

Haredim make up between 11% to 14% of Israel’s population. They are expected to become an even larger portion of the population in the coming years, as the birth rate in Haredi communities is significantly higher than in the rest of Israeli society.

Although they’re becoming a larger part of the population, Haredi society remains largely separated from the rest of Israel. They have their own education systems, most don’t serve in the military or national service (volunteer work in the emergency services or charitable or educational organizations), and a significant percentage don’t join the workforce. Many in Israel fear that this system is quickly becoming unsustainable, and some feel that non-Haredi Israelis are carrying an unequal burden in the economy and the national service.

Many Haredi education frameworks exclude math, science, and English, making it more challenging for Haredim to join the workforce, especially in high-earning fields. In 2024, only 16% of Haredi students qualified for a high school matriculation certificate, and Haredim only made up 5% of the total population of higher education students, according to the Israel Democracy Institute.

A study by the Kohelet Forum, published in June 2024, found that non-Haredi Jewish households pay approximately NIS 6,000 (about $1,800) more in taxes each month than they receive from the government through government services and benefits. However, Haredi households receive about NIS 4,000 (about $1,200) more in government services and benefits each month than they pay in taxes. (Arab Israeli households also receive more in services and benefits than non-Haredi Jewish households. In recent years, the status, rights, and national service obligations of Arab Israelis have been increasingly brought up in public discussions that used to focus primarily on the Haredi community.)

While the military draft, education, and taxes may seem unrelated, all of these issues are part of a much larger debate.

What role should Haredim play in broader Israeli society? Is it more important to ensure that everyone has the freedom to live and practice religion the way they want, or to ensure that everyone carries the financial and national service burdens of the state equally? Are there other services that Haredim provide, like Torah study, that make an imbalance acceptable? Among the Haredi groups that reject the legitimacy of a Jewish state, should they still be required to serve? If they don’t serve, should that affect their benefits, or even their rights? (Similar questions are also increasingly being asked about other parts of the population that aren’t fully integrated, including Arab Israelis)

Why is drafting Haredim so controversial?

In Israel, all citizens are legally required to register for the draft at the age of 18, though not all are ultimately drafted into the military.

Exemptions are granted for various reasons, including to married women and mothers, individuals with specific medical conditions, women who observe Shabbat and keep kosher, and Arab Israelis, among others.

Despite not fitting into one of the standard exemption categories, Haredi yeshiva students typically receive a “deferral” from military service, allowing them to avoid the draft by declaring that “Torah study is his work” and demonstrating full-time study in a yeshiva.

This arrangement, which has been in place since the state’s founding, was initially agreed upon by Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, to exempt a few hundred students.

Since then, however, the number of Haredi youth who use the arrangement has surged to tens of thousands, leading to increased criticism from other Jewish citizens who are required to serve.

Already in 1998, the High Court of Justice (part of Israel’s Supreme Court) ruled that the exemption was too large and needed to be regulated to ensure that some Haredim were drafted.

A commission known as the Tal Committee got to work on a new law to make the arrangement more equitable. In 2002, a law was passed providing a deferment of service to yeshiva students who spent all day in yeshiva. Once they reached 22, these students would need to decide whether to join the army for a little over a year or do a year of national service. The idea was that the law would eventually lead to increased recruitment among Haredim.

However, after several years, the state realized that the law wasn’t actually leading to an increase in enlistment. In light of the failure, in 2012, the High Court of Justice ruled that the law had failed to serve its purpose and violated the right to equality.

Since then, the issue has jumped between the government and the courts. Many governments since have relied on the Haredi parties as coalition members, making it nearly impossible for them to pass legislation on the issue that the courts would approve.

The Haredi parties have usually refused to consider any law that would lead to widespread enlistment among Haredi young men, so the laws passed have largely just extended the existing exemption without any changes. The parties have said that they oppose enlisting any Haredi young men due to concerns that interactions with less religious or secular Israelis during their military service would cause them to leave the ultra-Orthodox way of life. They have also presented the issue as a threat to the full-time Torah study that many Haredi young men focus on, although they’ve also often rejected proposals to only draft young men who don’t spend their days in yeshivas.

In 2018, debates surrounding the law contributed to the dissolution of the 20th Knesset, leading to a series of successive elections and short-lived governments.

Since then, discussion of the issue somewhat abated until the start of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current government.

As Netanyahu’s new government was being formed, the right-wing Likud Party signed agreements with Haredi parties to pass a law exempting yeshiva students from the draft.

The issue was temporarily sidelined due to the Oct. 7 attacks and the war in Gaza, but resurfaced in February 2024 when Israel’s Defense Ministry proposed laws to increase IDF service length due to manpower shortages. The IDF says it needs 10,000 more soldiers than it has, including about 6,000 combat soldiers.

The announcement sparked outrage and renewed the conversation about requiring Haredim to draft, as opponents argued that the manpower shortage could easily be dealt with by requiring Haredim to share the load.

Then, last March, the High Court of Justice ruled that the state couldn’t wait any longer and needed to start drafting Haredim.

The previous law exempting Haredim expired in June 2023, technically requiring the IDF to begin drafting those currently exempt. However, the government decided not to draft them while working on a new law.

Efforts to reach an agreement on a new bill were unsuccessful, despite meetings between Prime Minister Netanyahu, government officials, and Haredi party leaders. Ultra-Orthodox leaders warned that any bill with significant recruitment quotas or financial sanctions could cause them to leave the government.

However, many members of both the opposition and the coalition have demanded that any new bill include such quotas and sanctions to ensure it can actually be enforced.

Repeated efforts were made over the past year to reach some kind of compromise, but both sides refused to drop their demands and couldn’t reach an agreement.

Haredi Israelis gather prior to a military graduation ceremony on May 26, 2013 in Jerusalem, Israel. The Netzah Yehuda battalion was formed in 1999 with the aim of creating a unit to allow Haredi Israelis, traditionally exempted from compulsory conscription, to take a role in the military. (Photo by Lior Mizrahi/Getty Images)

Earlier this year, the IDF announced it would be sending out tens of thousands of draft orders to Haredi young men, following the existing law requiring everyone to be drafted equally. The IDF added that it would act to enforce the law against anyone who didn’t show up for the draft as required. In the months since, several dozen Haredi young men were arrested.

In June, the government nearly collapsed after the Haredi parties threatened to withdraw from the government and vote for early elections. At the last minute, an agreement on certain principles was reached between the Haredim and Likud MK Yuli Edelstein, who at the time served as the chair of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee. In light of the agreement, the vote for early elections failed, and the government remained in power.

About a month later, Edelstein was removed from his position as chair of the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee after he insisted on including sanctions and quotas in any new laws relating to the draft issue. He was replaced by Likud MK Boaz Bismuth, who in recent weeks presented his own proposal for a new law.

The proposal would set a goal of recruiting 4,800 Haredim within a year. Part of that goal will include recruitment to other services, such as Magen David Adom, the Fire and Rescue Service, and the police.

If after a year, at least 3,600 Haredim haven’t been drafted, certain sanctions will take effect, including the removal of government grants given to Haredim for daycare, discounts on public transport and in social security services, and housing benefits. If two years later the recruitment goals still aren’t met, additional benefits will be cancelled.

The definition of who counts as Haredi for the law has also been lightened compared to past proposals. This will allow people who may not be considered socially to be part of the Haredi sector to be counted as fulfilling part of the recruitment quota.

For now, the proposal remains heavily debated within Israeli society. Some feel it doesn’t include strong enough measures for enforcement or won’t recruit enough people to help the manpower crisis the IDF is facing. Others feel it’s sufficient, and some (particularly those within the Haredi community) think it’s too strong.

The bill still needs to be discussed by the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee and presented in four rounds of voting in the Knesset plenum before becoming law. For now, discussions in the committee have been delayed as the Prime Minister and legal advisors continue to review the proposal.

Despite ongoing discussions, Haredi leaders decided over the past week to hold what they called a “Million Man” protest to express their demands for maintaining a broad draft exemption for Haredi young men.

Why did the protest happen now?

Haredi leaders have warned several times over the past few years that they would hold a mass rally similar to the one organized this past week. A demonstration like this was seen as a last resort, to be used only when the situation seemed dire. Kikar Hashabbat, an Israeli Haredi news site, reported that leading rabbis in the Haredi community were waiting for the “perfect timing” to use this “weapon which could only be used once.”

A similar demonstration was held in March 2014, when approximately 500,000 Haredim protested a proposed bill that would have required many Haredi young men to serve in the military, with severe penalties for those who refused. The law was approved a few days later, regardless. However, in 2015, amendments were passed that effectively cancelled the measures of the original law, leaving the question of how or if to enforce any penalties entirely up to government ministers.

According to Kikar Hashabbat, the decision to move forward with this past week’s protest was made after a yeshiva student from the Ateret Shlomo yeshiva was arrested for failing to show up for the draft. The arrested student was close to Rabbi Moshe Hillel Hirsch, a prominent yeshiva leader and one of the main heads of the protest against the draft.

Several dozen yeshiva students have been arrested over the past year. While small protests have been held near Haredi neighborhoods, they didn’t spark a response from the Haredi leadership like the response shown this past week.

While the final decision was made to hold the protest, not all of the Haredi leadership were on board. According to Kikar Hashabbat, some Haredi leaders felt that it wasn’t the right time to advance such a significant move, considering that the government was just about to present its new proposal on the issue, a proposal that has received backing from at least some Haredi leaders.

A senior member of the Sephardi Shas party told Kikar Hashabbat that rabbis from the Sephardi community were upset that the rally was being held only now.

“To this day, they have only arrested Sephardi yeshiva students, and it has not interested anyone, except perhaps for a publicity stunt in front of Prison 10 (the prison where draft dodgers are often held). Suddenly, when a young man from an Ashkenazi yeshiva is arrested, everyone wakes up. Where is our honor?” the Shas party member said.

Several of the banners and speeches at the protest rejected any recruitment among Haredi young men, even among those who aren’t studying in yeshivas.

Tens of thousands of Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Jews gather to protest against mandatory military service during the ‘Million March’ demonstration in Jerusalem on October 30, 2025. (Photo by Mostafa Alkharouf/Anadolu via Getty Images)

A declaration issued at the end of the protest by the event organizers expressed a firm demand that the old arrangement, which has provided a broad draft exemption for Haredi young men for years, remain in place. They stressed that the law must ensure that “anyone who wishes to study Torah may do so without restriction or interference.”

The organizers also expressed outrage that yeshiva students were “shamefully arrested,” calling it a “serious violation of the right of choice of these Torah scholars to dedicate their lives to studying the Torah and contemplating it, and even an infringement of religious freedom as pledged in the laws of the state.”

The organizers singled out the judicial branch of government, accusing it of issuing rulings that “stem solely from a desire to harass Torah students and hinder their steps.”

While the protest was among the larger demonstrations held in Israel’s history, it was significantly smaller than the last “million man” march in 2014. Whether this difference in size was due to disagreements among the Haredi leadership, differences of opinion within the Haredi community, or simply logistical issues caused by traffic jams and public transportation problems is unclear.