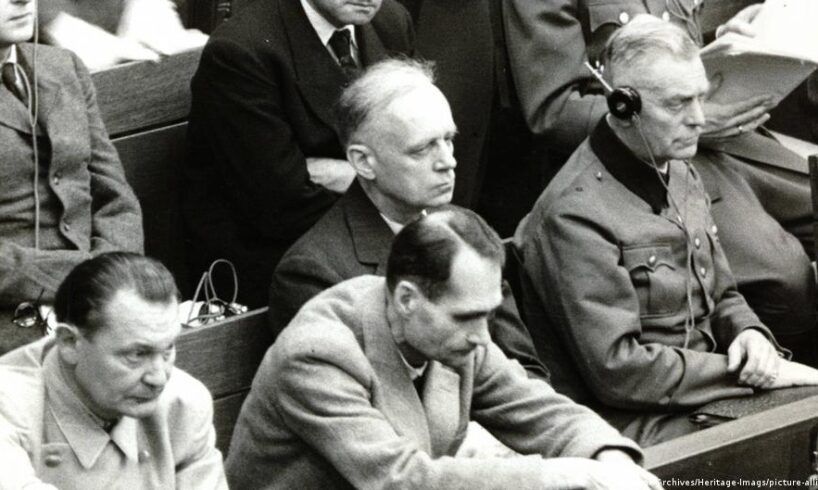

“I hereby indict the following persons for crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity: Hermann Wilhelm Göring. Rudolf Hess. Joachim von Ribbentrop…”

Courtroom 600 in Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice was filled to capacity as Chief Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson read out a list of names, one after the other. His list was long. The Major War Crimes Trial against 24 high-ranking representatives of the Nazi state began on November 20, 1945, in the southern German city of Nuremberg.

Over the next 218 days, more than 230 witnesses were questioned, 300,000 statements were read out, leading to 16,000 pages of transcripts.

The choice of Nuremberg as the venue for the trial was not arbitrary. The Bavarian city had previously been the scene of the Nazi party rallies. It was here that the Nazi regime showcased its power, and it was here that the Nuremberg Laws were proclaimed — the racist and antisemitic laws that paved the way for the Holocaust. And that is precisely why justice was to be administered here.

Crowds celebrating Hitler at the Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg in 1933Image: akg-images/picture-alliance

The crimes could not go unpunished

It was the first time ever that leading representatives of a state were held personally accountable for their inhumane deeds. This was something new in the system of international law. There was one thing that those victorious over Germany — the United States, Britain, France and the Soviet Union — agreed on: the crimes of the Third Reich must not go unpunished. Millions of people had fallen victim to the Nazi regime — murdered in concentration camps, through war, hunger, enslavement and forced labor.

Another important factor that was being addressed for the first time was the question of individual guilt. “Up until that point, a state leader like Hermann Göring [one of the most powerful figures in Nazi Germany] could have relied on Germany, the state he was acting on behalf of, being held responsible, and not he himself — and this is probably what he expected to happen,” legal scholar Philipp Graebke told DW.

No one pleaded guilty

When the trials began, one defendant after another pleaded “not guilty.”

“The mass killings exclusively and without influence were carried through by order of the head of the State, Adolf Hitler,” announced Julius Streicher, a fanatical antisemite and editor of the inflammatory newspaper “Der Stürmer,” which spread Nazi propaganda for years.

Chief Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson led the trials against the defendants, who claimed they knew nothing Image: National Archives, College Park, MD, USA

In his capacity as president of the Reichsbank, Walther Funk, Hitler’s personal press chief, denied Jews access to their bank accounts. Moreover, he directed that the valuables of Jews who had been murdered in the extermination camps, including their dental gold, be sent to the Reichsbank.

In Nuremberg, he testified in court: “No one lost their life as a result of actions I ordered. I always respected other people’s property. I always sought to help people in need. And, as far as I was able, to bring happiness and joy into their lives.”

Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, one of the people responsible for building the first concentration camps, also confidently proclaimed his innocence. “As far as I am concerned, I have said that I did not know, even approximately, to what extent these things were taking place,” he replied when asked whether there had been a policy aimed at exterminating the Jews. He claimed to have only known about the plans for the emigration of the Jews and not their extermination.

Hermann Göring also pleaded ‘not guilty’ — and later escaped the death penalty by committing suicideImage: akg-images/picture alliance

Twelve death sentences, seven prison terms

The senior Nazis showed no remorse and systematically placed the blame solely on Hitler. Hitler, however, could no longer be prosecuted, having committed suicide in the final days of the war.

But all attempts at denial were of no avail. The evidence was overwhelming. Films from concentration camps. Testimony from survivors. Letters and orders from the perpetrators. For the first time, the world saw the atrocities that had been committed in the camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen.

Concentration camp prisoners in Auschwitz after liberationImage: akg-images/picture alliance

The first Nuremberg trial ended on October 1, 1946. The court handed down 12 death sentences, seven prison sentences and three acquittals against the high-ranking Nazi leaders.

The German public viewed the trials as ‘victors’ justice’

“When the defendants were convicted, most Germans thought, ‘Now we’ve got the real culprits, and that’s that,'” says Bernhard Gotto of the Institute for Contemporary History.

His colleague Stefanie Palm adds: “The Nuremberg Trials established a certain narrative among the German population. … Everyone else had merely carried out orders, had been mere followers and were not to blame!”

“A kind of victim perspective was adopted: ‘We are the victims of this small clique around Hitler’,” she says.

In this respect, most Germans were opposed to the 12 subsequent trials against lawyers, doctors and industrialists. The tribunal was seen as a “victor’s justice,” says Gotto, “because it immediately raised the question of how far responsibility for Nazi crimes extends. Suddenly it’s no longer just Göring and Keitel, the Wehrmacht, Himmler and, of course Hitler, who had supposedly seduced the Germans. The burden of guilt is then spread across more shoulders, and the majority of Germans were unwilling to accept that.”

The legacy of the Nuremberg Trials

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Precursor to International Criminal Court

Today, the Nuremberg Trials are considered a milestone in international law. In 1945, it was hoped that the legal standards that applied in Nuremberg would apply to everyone in the future. No war criminal should be able to rely solely on the power of their office or the laws of their own country.

“If we assume that international criminal law first appeared in the courtroom of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice in 1945, we can really draw a direct line from the UN war crimes tribunals of the 1990s to the establishment of the International Criminal Court,” says legal scholar Philipp Graebke.

“However, this certainly did not lead to the seamless enforcement of international criminal law from 1946 onwards, nor do we see this today,” he notes.

It was not until 1998 that the International Criminal Court (ICC) was established in The Hague, and it began its work in 2002. But not all states recognize it. Among the 125 signatory states, the most important major powers are missing: the US, Russia, China and India. Israel does not recognize the court either.

What power does the International Criminal Court have?Image: Peter Dejong/AP Photo/dpa/picture alliance

Is the ICC just a paper tiger?

But even countries that recognize the ICC have ignored arrest warrants.

So far, the rule for those leaders who have been accused has been: If you don’t want to go to jail, just stay home. Now, even that is no longer necessary. Russian President Vladimir Putin is wanted on an arrest warrant for the abduction of Ukrainian children to Russia. But in September 2024, he traveled to Mongolia, which is highly economically dependent on Russia, and was received there with full honors.

Mongolian President Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh welcomed Putin with full honorsImage: picture alliance/dpa/Russian President Press Office

What’s more, the ICC was unable to indict Putin for his war of aggression against Ukraine. In contrast to crimes against humanity, the court can only prosecute a head of state for ordering an invasion if that country also recognizes the ICC.

There is also an arrest warrant out for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. According to the ICC, Netanyahu allowed Palestinian civilians to be starved and killed. But during Netanyahu’s visit to Hungary at the end of 2024, Prime Minister Viktor Orban demonstratively assured his guest safe passage.

In Germany, too, Netanyahu would presumably be left untouched.

“I find it completely absurd that an Israeli prime minister cannot visit Germany,” said newly elected Chancellor Friedrich Merz in February of this year, a stance also adopted by his predecessor, Olaf Scholz.

Whether a war criminal is ultimately brought before the judges therefore depends on the diligence of the member states. The Hague itself lacks the resources and powers to bring suspects to trial.

This article was originally published in German.